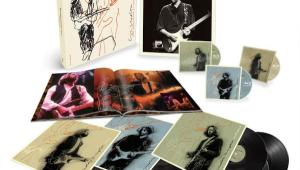

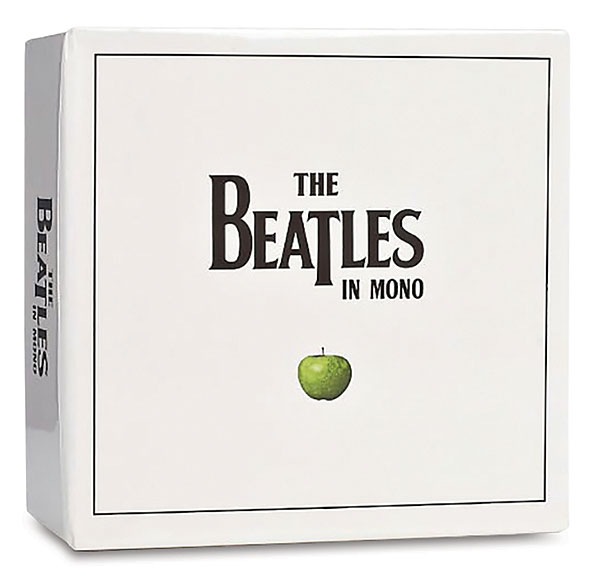

Get Back to Mono Page 2

Of the song originally tracked in January 1967 as “In the Life Of…,” Magee observes, “That was cut completely flat. The notes on the original tape said, ‘Please cut flat.’ So that’s exactly what we did.” Berkowitz is especially proud of the outgroove—that is, the infinite loop of nonsense chatter that follows “Life” and the ever-mischievous high-frequency 15- kilohertz tone. “It’s fantastic! And we didn’t even have that on the American version,” he says enthusiastically. “Once it was perfect, Sean had to cut it nine times to time it exact for that locked, infinite loop.” (“And 15 times for the stereo version!” Magee clarifies.)

Understanding All You Hear

At the outset of the mono project, the team spent a lot of time listening to original 1A mono pressings to establish a baseline, and they utilized a Studer A80 tape machine to play back the original master tapes—with extreme care. “We went into the room on the third floor where the records had originally been cut by Mr. Harry Moss [Abbey Road’s cutting engineer]—the same space, and the same locations of the lathe,” details Berkowiz. “The first thing we did was take the original approved albums and convert them to flat 96-kHz/24-bit into ProTools so we didn’t have to play the tapes too many times. Then we took the original tapes that made each record, tracked them flat into ProTools in parallel, took the most recent mono CDs that Sean had also worked on, tracked them in flat, and then set about listening to them all. We went direct to acetates and lacquers—completely analog and nothing in the middle; just flat straight through.”

Was the potential fragility of any of the original tapes, some of which are more than a half-century in age, a concern? “Considering that some tapes were 50 years old, there were very little issues with shedding and stuff like that,” Magee reports. “The biggest problem, really, was heads falling apart, as they kind of do after a little while. For Please Please Me [released in March 1963], we had to make a new master for that for cutting—a flat envelope transfer, because there was glue left over from the original edits sticking to the head, which was causing some extra friction of the tapes passing through the transport. So rather than risking any possible damage, we transferred each track clean to move through the transport, and then transferred that onto a new analog tape and cut that together for this project. Other than that, everything else was just as it were.”

And being able to hear distortion in mono is a beautiful thing. “How about the edge in John’s voice in ‘Money’ [from November 1963’s With The Beatles]?” marvels Berkowitz. “Sean worked really hard at the inner-groove distortion. I often wondered if they put ‘Twist and Shout’ and those other serious rockers in the center groove—the closest groove—on purpose. I’ve never asked. It’s interesting that the loudest, most raucous, and most distorted tracks on the first three or four records were put on the inner band, and there’d be inner-groove distortion—and, well, distortion is beautiful!” (That’s how you shake it up, baby…)

The Quieter Beatles

One important executive sonic decision was to have the new vinyl not be as loud as the original vinyl. In other words, Jo Jo: No Loudness Wars here. “They are slightly quieter,” Magee concedes. “We didn’t really feel there was much need for them to be crazy loud, because The Beatles are not competing with new artists, nor have they ever been. Everybody else is. They want to cut as loud as possible, and the extra problems you have there is with sibilance. A track like ‘Money’ would have extra distortion in it, created by itself, and we thought you’d want to hear what was on the original tape, so we turned it down a little bit. You can get away with a little mess of signal-to-noise ratio on today’s vinyl. But if you’re comparing these to the original ones, you might want to turn your volume knob to the right.”

Adds Berkowitz, “For the first three or four records, the cutting engineer would take the finished tape and cut it so it played as loud as it could with the bottom as loud as you could go without making it skip. But by the time you get to Sgt. Pepper, the engineers are more concerned about how the sound is going to resolve when it’s cut, and there’s suddenly something that starts being called ‘mastering.’”

Here, There, and Everywhere

“Whatever system you play the records on, these will be the best versions of The Beatles you will hear,” affirms Hayden—and I concur. “Unless you happen to have a 1A pressing from back in the day—and even then, it’s old, it’s scratched, and it’s grainy.” (Like an old brown shoe…)

Concludes Berkowitz, “What would you do to the records that changed the world? And, remember, for the most part, they changed the world in mono, as this is the way many people heard them. The goal was clear, because the record is the document. That’s the Mona Lisa. It’s not the sketches, it’s not the studies. The record is it. It’s what they made, it’s what they approved, and that leads to the stated goal: to try and replicate the records in the way George Martin and The Beatles intended for them to sound—and the way they did sound.” And thanks to the tireless efforts of Messrs. M. and B., and all those who toiled to bring us The Beatles in Mono on pristine virgin vinyl, The Fab Four did indeed finally get back to where they once belonged. And their production is second to none.