Flashback 1999: MP3-for-All

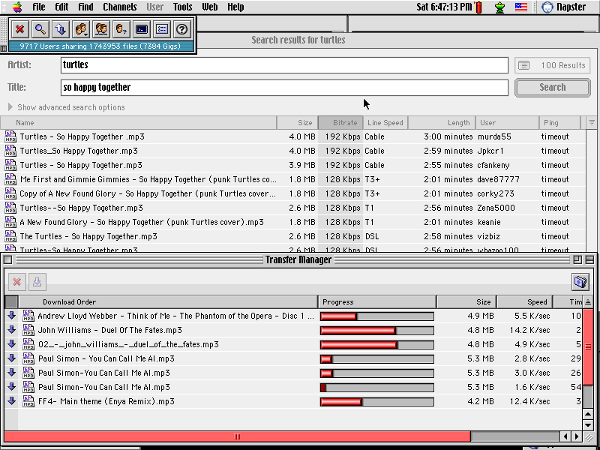

I’m of course talking about the file-sharing service known as Napster, which made its presence known to Internet-savvy users two decades ago on June 1, 1999. Napster was an independent peer-to-peer (a.k.a. P2P) file-sharing service that made it possible for just about anyone to access in digital form just about every song recorded. Indeed, Napster was the gateway portal to a virtual lending library whose only limit seemed to be how much hard-drive space its fervent user base could spare.

At the height of its popularity, Napster boasted over 80 million registered users, but it ultimately fell prey to the two cardinal sins of rock & roll by both burning out and fading away in 2001 due to incontrovertible issues related to copyright infringement and piracy. After having gone through subsequent periods of litigation, dormancy, acquisition, and resuscitation, Napster was rebranded under the auspices of Rhapsody in 2016 as a subscription-based streaming service.

For those of us who live and breathe in the audiophile community 24/7, the great divide that occurred with the original Napster was via its relationship to sound quality, or lack thereof. To us golden-ear types, MP3 is a perpetual four-letter word, and most Napster files, to be blunt, were simply not up to audiophile snuff. That said, anyone who claims to have never used Napster and/or any of-era file-sharing equivalent — Gnutella, Kazaa, LimeWire, Grokster, et al — is probably flat-out lying. Finally, everyone could partake in a veritable Whitman’s Sampler of music — songs we never had access to before because we either couldn’t afford to buy them, had never even heard of them, or wanted to try them out without financial regret.

Once you were in the Napster ecosphere and got the hang of its relatively painless open-share navigation, the virtual hunt was on! How many different live versions of Bruce Springsteen’s “Point Blank” could you compile? Who had the complete set of in-studio outtakes, false starts, and mostly final mixes from Brian Wilson’s ill-fated Beach Boys SMiLE Sessions? Did anybody put up an unedited file of the radio-broadcast version of The Tragically Hip’s seminal “New Orleans Is Sinking” with vocalist Gord Downie’s extensive “Killer Whale Tank” improv rant from their live performance at the Roxy in West Hollywood on May 3, 1991? Were you willing to grant entrée to the three full album offerings from Aphrodite’s Child, the late-1960s Greek progressive triumvirate featuring keyboardist/flautist Vangelis Papathanassiou, the man later known by his first name only when he composed the Academy Award-winning score to 1981’s Chariots of Fire?

But much like the way your stomach reacts after having ingested a tub of Rocky Road in one sitting, the painful pangs of reality would set in. How many GBs of storage could you then afford to set aside solely to house music files? Were you ever really going to listen to many multiple-thousand P2P-accessed songs? Did you have any ethical qualms about depriving artists their rightful due of being paid for their work you were acquiring en masse?

Napster’s initial fate was sealed once the legal powers that be in the music business stepped in, but the impact on how music was accessed from that point forward could not be overlooked — or reversed. Once the floodgates were opened to the idea of nonpaid music, they could never be sealed. Sure, there are those of us hardcore audiophiles willing to lay down our hard-earned dosh for high-quality physical and digital product that reflects the SQ principles we demand, but after the masses got a taste of “free MP3s for all!” — well, they were irrevocably hooked.

I look at it like this: While I may have a core philosophical difference with how Napster got it all started, no revolution truly dedicated to enacting change is bloodless. Like it or not, Napster 1.0 forged the path that led to the rise of streaming — which can and should be consumed as often as possible in subscription-based, hi-res fashion.

Perhaps Dickens put it best in the following lines of his Two Cities intro: “It was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness. It was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity.” Verily, while this pioneering P2P service may have broken the seal on the system it was intended to celebrate, rather than suffering from an incurable case of Napster dread, I say instead: Vive la révolution!

Related:

Flashback 1996: U.S. Grants MP3 Patent

Flashback 1998: A Compressed History of the Digital Music Player

Flashback 1998: Birth of the MP3 Player