Flops: Fourteen Formats and Technologies That Couldn't Quite Hang On Page 2

The logical successor to the vaunted VCR had finally arrived when the first standalone DVD recorders reached store shelves in late 2000 (Panasonic) and early 2001 (Pioneer)—or so it seemed. Unbeknown to all but the shrewdest pundits, the successor had actually arrived a year earlier in the form of the hard-disc-based personal video recorder, or PVR, offered by two companies with catchy names—TiVo and ReplayTV.

Over the next few years, these innovative devices would leave DVD recorders in the dust as they transformed the way America watched TV. With their ability to record and play at the same time, viewers could pause live TV and collect and rate favorite shows for later viewing without having to mess with timers and search for programs in novel ways. Looking back, it’s easy to see why what we now call the DVR (digital video recorder) became a staple of cable and satellite TV boxes.

Compared with the DVR, DVD recorders were cumbersome to operate and hampered by confusion over an alphabet soup of competing formats: DVD-R/RW, DVD+R/RW, and DVD-RAM. On top of that, initial prices were high and recordable DVD drives were becoming popular in PCs. Even combo VCR/DVD recorders and DVD recorders with hard drives couldn’t save the category. That’s not to say standalone DVD recorders are extinct: You can still find a handful of new and refurbished models in the $100-$300 range.

SUPER AUDIO CD & DVD-AUDIO (1999-2000)

SUPER AUDIO CD & DVD-AUDIO (1999-2000)

As the 20th century came to a close, the music business was on the cusp of disruptive change. The LP was all but dead, the almighty CD had reached its zenith, and millions of college kids were flocking to a start-up, peer-to-peer service called Napster that let them quickly and easily download and share MP3 music files over the Internet. It was—quite literally—a free-for-all. The RIAA responded with a $20-billion suit that ultimately led to a court-ordered shutdown of Napster in 2001. It was the beginning of a new era for music and audio.

While Apple was busy perfecting the iPod and figuring out how to build a business around the inescapable force of digital music, record labels were chasing online pirates and looking for a foolproof digital rights management (DRM) system to stop piracy. So it made perfect sense that they would introduce a sleek, new class of audiophile recordings…in not one, but two formats: first Super Audio CD (SACD) from CD codevelopers Sony and Philips and then DVD-Audio, an industry-developed format supported by virtually every major label and many big-name audio companies.

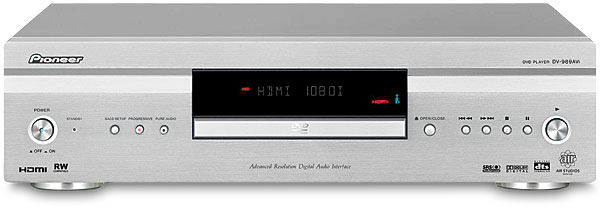

SACD started life in the fall of 1999 as a tweak format with the launch of a $5,000 Sony player and 19 (mostly classical) Sony Music titles priced at $25 each. Although the format was capable of multichannel surround sound, early players and discs played only stereo SACDs and regular CDs; multichannel players and discs would come a couple of years later. After several false starts, DVD-Audio stumbled into the market a year later, led by a $1,000 Panasonic player and a small, eclectic mix of pop, jazz, and classical titles, also priced around $25. Players were touted as universal machines that played CDs, regular DVDs, and the new, high-res DVD-Audio discs, which served up music mixed for 5.1-channel surround sound, DVD-like menus, and multimedia extras such as videos, interviews, lyrics, and photos. A Warner Music exec who was at the forefront of the launch said DVD-Audio would be looked back on as “a milestone similar to the move from mono to stereo.” Actually, it would be all but forgotten before the end of the decade.

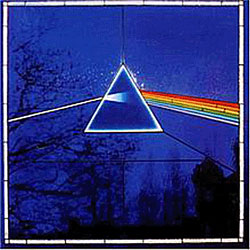

Enthusiasts and industry insiders had high hopes for both formats, which followed different paths to the same goal: ultrahigh-resolution sound that would blow away the CD. SACD used Direct Stream Digital (DSD) technology to reach sonic nirvana, while DVD-Audio pushed DVD to its limits by employing more bits and higher sampling rates. Listening to a well-recorded and mixed multichannel SACD or DVD-Audio disc on a good surround-sound system was (and still is) a riveting you-are-there experience (the SACD 5.1-channel mix of Pink Floyd’s seminal Dark Side of the Moon comes to mind). But no matter how wonderfully rich the experience, mainstream America didn’t care or perhaps didn’t even notice the new formats. Confusion at retail made it all but impossible to find these special discs, which often ended up mixed in with regular CDs or buried somewhere in the back of the store. High hardware and disc prices and a slew of lackluster classic rock remixes on DVD-Audio didn’t help the cause.

Audiophiles alone were responsible for any discs that were sold, which wasn’t many. Sales of both formats combined peaked in 2003 at 1.7 million units, with SACD capturing 1.3 million—it’s largest year ever. To put these numbers into perspective, total music sales for that year were about 800 million units, with CD accounting for 93 percent and SACD/DVD-Audio 0.002 percent. DVD-Audio sales peaked at 0.5 million in 2005 before being abandoned by the major labels.

SACD lives on as a niche format, supported by a small but fervent band of audiophiles around the world and is available to anyone who owns one of several universal Blu-ray players that spin SACDs and DVD-Audio discs. Thousands of SACD titles are available online through sites such as acousticsounds.com, and indie labels such as Mobile Fidelity and Chesky Records still release SACDs. Even DVD-Audio refuses to completely go away—DVD-A.net reported on a handful of new titles in 2011. If we learned one lesson from these formats, it’s that mainstream America continues to choose convenience and portability over sound quality.

FLASHES IN THE PAN

Formats come and formats go. Some are so fleeting that it takes an article like this to remind us that they ever existed in the first place. Here’s a look at three transient technologies.

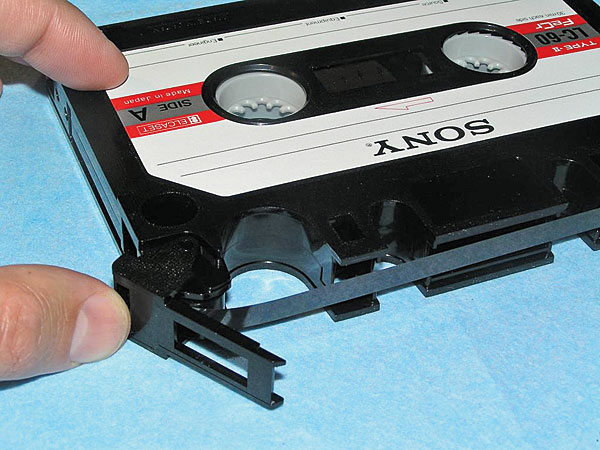

ELCASET (1977)

1977 was the year of Star Wars, which gave us Luke Skywalker, and Saturday Night Fever, which gave us shiny polyester shirts and ignited the disco inferno. It was also the year Sony introduced an enthusiast tape format with a curious (OK, unfortunate) name: Elcaset. That’s right, Elcaset with one s and one t—a moniker apparently concocted by some marketing genius to convey “Extra large cassette.” Sounds to me like something you’d find at Taco Bell, but I digress.

Hailed in magazine ads as delivering “high-fidelity specifications never before imaginable in a cassette system,” Elcaset combined the superior fidelity of bulky reel-to-reel tape with the convenience of the Compact Cassette. Sound quality was enhanced by doubling tape width (⅛ to ¼ inch) and running speed (1 ⅞ to 3 ¾ inches per second, or ips—same as 8-track), which improved frequency response and reduced noise and distortion; the trade-off was a tape shell that was twice as big as a regular cassette, yet still portable and fairly compact. To deal with wow and flutter—the ability of a tape deck to run at a consistent speed and the Achilles’ heel of cassettes—the transport in an Elcaset deck actually pulled the tape out of its shell and guided it across the playback and recording heads instead of moving the heads to make contact with the tape as is done with a regular cassette.

As noted in the owner’s manual for Sony’s top-of-the-line EL-7 deck, which sold for upwards of $1,000—a chunk of change today, let alone in the late ’70s—Elcaset offered advanced features that weren’t available on the cassette, including tape protectors, reel stoppers, erasure-proof tabs, and automatic shutoff.

Elcaset was a noble effort at providing improved fidelity in a format that was portable and far more convenient than clunky open-reel machines, but it was overpriced and too late to the party to win over die-hard recording enthusiasts who either stayed the course with reel-to-reel or moved to cassette with the arrival of high-end decks from Nakamichi. [Editor’s Note: See this month’s Vintage Gear in Perfect Focus for a look at the famed Nakamichi Dragon.] In the end, Elcaset decks didn’t offer enough of a performance edge over cassette to woo the masses, and its tapes were incompatible with the millions of cassette decks already in consumers’ homes.

Visit elcaset.ca for Geraint Tuck’s painstaking overview of the Elcaset format, complete with dozens of photos.

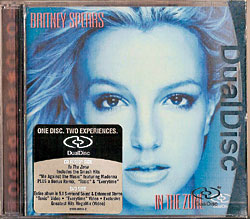

DUALDISC (2005)

We’ve come to expect warnings on a pack of cigarettes, but on an audio disc? DualDisc was the half-baked product of an out-of-touch music industry that was quickly losing control. In the mid-2000s, cash-cow CD sales had dropped to levels of a decade earlier, and Apple’s iTunes Music Store became an overnight sensation, selling more than 100 million downloads in its first 15 months. Instead of hunkering down to focus on building a viable online business, old-guard record labels plodded along with hobbyist formats and introduced the two-sided DualDisc in a futile effort to stave off the inevitable decline of physical media.

DualDisc was conceived as a high-value CD with a DVD on the flip side that offered a surround-sound mix of the album and multimedia extras such as band interviews, all for just a few bucks more than a regular CD. It was an interesting idea, except for one problem: The tricky process of bonding CD and DVD layers together produced a kludge of a disc that could not be guaranteed to work with any CD player. In fact, CD codevelopers Sony and Philips would not permit DualDiscs to carry the CD logo because they didn’t meet the format’s rigid specs.

DualDisc was conceived as a high-value CD with a DVD on the flip side that offered a surround-sound mix of the album and multimedia extras such as band interviews, all for just a few bucks more than a regular CD. It was an interesting idea, except for one problem: The tricky process of bonding CD and DVD layers together produced a kludge of a disc that could not be guaranteed to work with any CD player. In fact, CD codevelopers Sony and Philips would not permit DualDiscs to carry the CD logo because they didn’t meet the format’s rigid specs.

The labels shrugged and shipped millions of discs with a printed warning that the disc might not play on all CD players, especially slot-loading players and megachangers. A number of hardware companies issued compatibility warnings and statements advising customers that any disc or player damage resulting from playing a DualDisc would not be covered under warranty. Shortly after the DualDiscs hit retail shelves in late 2004 and early 2005, reports of playback problems and retail returns began trickling in.

First-year sales for Sony BMG were in the millions, but the figures were misleading because many high-profile albums, including Bruce Springsteen’s Devils & Dust, were released only on DualDisc. Nearly half of all buyers didn’t even realize they were buying a special disc, according to an NPD survey. By early 2006, Warner, EMI, and other big labels were already backing away from the format in favor of CD/DVD combo packages, which were cheaper to produce and offered a clear-cut value proposition. By the end of the decade, DualDisc was dead and buried.

HD DVD (2006)

It’s the story of a classic, high-stakes format war between competing systems—in this case, two high-definition optical disc formats vying to succeed DVD as home entertainment’s Next Big Thing. Unlike the legendary VCR wars of the ’70s that started the home video revolution, this was a battle to claim what would likely be the last physical-media format. And unlike the forgotten SD (Super Density disc) versus MMCD (Multimedia CD) skirmishes of the mid ’90s, which preceded the launch of DVD, there was no 11th-hour truce clearing the way for an orderly market introduction. No, this was a messy, full-on, public war that pitted the Toshiba-led HD DVD format against the Sony-backed Blu-ray format.

High-definition disc players in both formats shipped to stores in 2006, following a year of tit-for-tat posturing, stalled unification talks, and pleas from all corners of the industry to avoid a format war. In an interview with Billboard magazine, one retail executive termed the failure to agree on a single format “criminal,” saying he and his sales staff wouldn’t know which format to recommend to customers. HD DVD hit stores a couple of months before Blu-ray, giving it an early advantage, but the war escalated quickly as more players and discs were introduced in both formats.

The one-upsmanship continued: HD DVD players were less expensive (and easier and cheaper to manufacturer), but Blu-ray was more forward looking and offered greater disc capacity. A steady stream of format news would tip the balance one way or the other: Sony said it would incorporate Blu-ray into its PlayStation 3; Microsoft countered with an HD DVD drive for it’s Xbox 360. Studio alliances shifted: Warner Bros., HD DVD’s biggest supporter, started producing Blu-ray titles alongside HD DVD, while Paramount dropped Blu-ray to support HD DVD amid whispers of big bucks and back-room deal making.

Things could have gone either way through 2006 and well into 2007—until Blockbuster announced an exclusive Blu-ray deal and an industry survey revealed that Blu-ray discs were outselling HD DVDs two to one. The crushing blow came in January 2008 when Warner Bros. announced it would stop releasing HD DVD titles to focus on Blu-ray. Less than two years after bringing the first HD DVD player to the market, a shell-shocked Toshiba conceded defeat, ending consumer confusion and paralysis over which format to buy, not to mention the retail problem of dual inventories. The story of HD DVD versus Blu-ray has become fodder for a case study on how not to launch a format. The question now becomes: How long can Blu-ray—or any physical format for that matter—survive in the face of growing competition from digital streaming, downloading, and video on demand? —Bob Ankosko