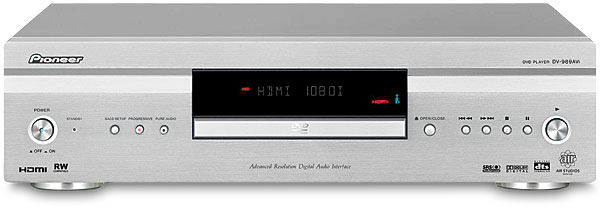

I don't think movies will follow the same route as music and become a (completely) non-tangible format. The reason for this is that the movie companies would not have control. With a disc, there is some form of copy control. This is not the case with MP3's. I know we can go to iTunes and buy digital movie files, but the means to play back these files is limited for your average American.

As for streaming movies, the issue is one of speed. To get good playback of streaming content, you need at least 10mps. I doubt 40% of this country runs that 'fast'. I don't think enough people want to pay for it at current prices.

SUPER AUDIO CD & DVD-AUDIO (1999-2000)

SUPER AUDIO CD & DVD-AUDIO (1999-2000)

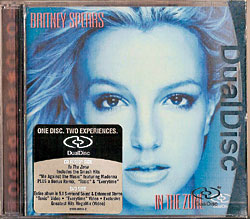

DualDisc was conceived as a high-value CD with a DVD on the flip side that offered a surround-sound mix of the album and multimedia extras such as band interviews, all for just a few bucks more than a regular CD. It was an interesting idea, except for one problem: The tricky process of bonding CD and DVD layers together produced a kludge of a disc that could not be guaranteed to work with any CD player. In fact, CD codevelopers Sony and Philips would not permit DualDiscs to carry the CD logo because they didn’t meet the format’s rigid specs.

DualDisc was conceived as a high-value CD with a DVD on the flip side that offered a surround-sound mix of the album and multimedia extras such as band interviews, all for just a few bucks more than a regular CD. It was an interesting idea, except for one problem: The tricky process of bonding CD and DVD layers together produced a kludge of a disc that could not be guaranteed to work with any CD player. In fact, CD codevelopers Sony and Philips would not permit DualDiscs to carry the CD logo because they didn’t meet the format’s rigid specs.