Embracing The Spirit of Neil Peart: An Aural Appreciation of the Late, Great Rush Drummer

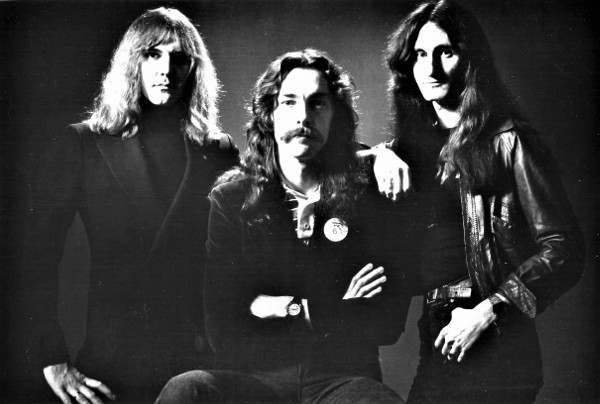

Neil Peart, perhaps the only man to inspire just as many air drummers as actual practicing drummers, passed away on January 7, 2020, following a long and private battle with brain cancer. The world-renowned, world-class drummer and chief lyricist for Rush, the perpetually progressive Canadian power trio, was 67 years old.

I had the privilege of seeing Rush live 24 times — the first being on December 13, 1981 in Roanoke, Virginia during the Exit Stage Left Tour, and the last being on June 27, 2015 in Newark, New Jersey for R40, their final tour. Watching Peart (aka ‘The Professor”) and his two Ontario-bred compatriots, bassist/keyboardist/vocalist Geddy Lee and guitarist/vocalist Alex Lifeson, recreate the wondrous and powerful sounds they concocted together in the recording studio live onstage was always a special event — especially Peart’s nightly drum solo, which always had a different character to it on every tour they did, and something he never played the same way twice.

Peart (pronounced, incidentally, as “Peert” and not “Pert,” as many uninformed talking heads got wrong this past week) opted for retirement following that final R40 tour. I had a feeling it was going to be Rush’s last live hurrah when they played both “Losing It,” a song from 1982’s Signals they had never done live before about artists of various creative disciplines recognizing they were moving past their prime, along with “Between the Wheels,” a Cold War-era screed from 1984’s Grace Under Pressure about the perils of watching life just pass you by if you don’t do something to change your circumstances. Better to go out on top rather than fade away with a whimper, I say — and so, apparently, Peart said as well, who reportedly never got behind a drum kit again for any reason once the R40 Tour ended in Inglewood, California on August 1, 2015.

Before they gained even more widespread acceptance leading up to and beyond their induction into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in April 2013, Rush was a band truly unique to the quite particular postwar Gen X experience. Indeed, they were among the very first recording artists to appeal to “the misfits and the dreamers” alike in a way that was never quite understood by the tastemaking cognoscenti of the initial rock era. But to those listeners who experienced each Rush album as a parallel soundtrack to their own lives and personal interests — yours truly very much included — Rush encapsulated the best of what you felt inside but couldn’t always easily express externally on your own.

One minute, Rush could be quite cosmic with the 20½ unabashed chance-taking minutes of the full-album-side title track to April 1976’s 2112; and in the next, they could chronicle the exact feeling of growing up as a suburban outsider, just as they oh-so-poignantly did with “Subdivisions,” the opening track to September 1982’s aforementioned Signals. Not only that, they could also marry their most progressive-oriented leanings with deceptively catchy radio-friendly arrangements, as witnessed by all 40 minutes of their career-best album, April 1981’s Moving Pictures (and one that also happens to be my own personal No. 1 album of all time, btw).

Choosing Peart’s best moments as a drummer is a difficult task given the abject breadth of his career work, but among my own personal favorites are the following: the dramatic, full-kit, across-the-soundstage fills during Moving Pictures’ “Tom Sawyer” (not to mention the abject drumming clinic that permeates every second of that same album’s “YYZ”); the monstrous power-drive charge of “One Little Victory,” the cut that opens up March 2002’s Vapor Trails; the swinging jazzy sequence in the back half of “La Villa Strangiato,” the final track on October 1978’s Hemispheres; and the opening and closing thud of “Force Ten,” the lead track of September 1987’s Hold Your Fire.

I suppose I could go on and on and on and continue listing many more impactful moments like those above, as Peart liked to challenge both himself and the listener with every choice he made behind the kit. And, rest assured, there are numerous classic Professorial moments to be cited and dissected accordingly (many of which have already been catalogued and analyzed to no end across the interwebs), but the bottom line remains this: Every recorded element of this man’s incredible body of work shows that Neil Peart’s passing is at a level of end-of-an-era significance on par with, if not even more heightened than, that of both jazz legend/innovator Buddy Rich and Led Zeppelin’s indomitable powerhouse, John Bonham.

Besides his prowess behind the kit, Peart was also a celebrated lyricist who prided himself on reflecting a self-taught, didactic and literate second nature that celebrated both the merits of unflinching introspection and wide-eyed wonderment with the universe at large. He tapped into the internal experience many teenagers and twentysomethings in the 1970s and ’80s felt internally but could not truly express in open forums in the pre-Internet era — namely because there wasn’t any easily found avenue to do so collectively. At times, the only arenas of true communion were to be found in concert halls all across North America, many of which Rush filled to the rafters on essentially every tour they undertook.

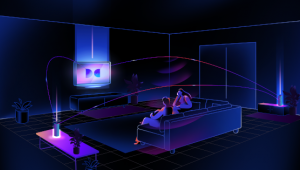

Over the course of 19 studio albums, 1 covers EP, and 11 live recordings, Rush tapped into and outright mastered the kind of prog-centric arrangements many a budding and card-carrying audiophile could readily embrace. Rush ultimately evolved from nascent analog kids into full-fledged digital men, adopting the permanently shifting waves of technology that enabled their often complex music to be best appreciated in a form most befitting their ambitions — namely, the glories of surround sound.

Lucky for us, a good portion of Rush’s rich catalog has seen such hi-res 5.1 upgrades to date — namely, February 1975’s Fly by Night, 2112, September 1977’s A Farewell to Kings, Hemispheres, Moving Pictures, Signals, and May 2007’s Snakes & Arrows (with hopefully much more to come in the years ahead).

Also, in recent years, Quality Record Pressings has reissued the band’s main Mercury and Atlantic-era catalog on 180-gram and/or 200-gram LPs as remastered by Sean Magee at Abbey Road Mastering Studios in London. We’ve also witnessed some of Rush’s latter-era live albums hit multi-disc wax for the first time as well, such as October 2003’s Rush in Rio and November 2011’s Time Machine 2011: Live in Cleveland.

But don’t just take my word for how important Neil Peart and Rush truly are to the overall rock pantheon. To that end, I reached out to a few musicians and producer friends to shed some light from their own personal and professional experiences with the man himself. “Neil had his own voice on the instrument, but even more, he had his own literary voice,” points out Styx drummer Todd Sucherman, a kitsmaster of the highest order who continues to top numerous readers’ polls in Modern Drummer year after year. “In particular, 2112 through Signals loomed large in my childhood. And I learned every single note of Moving Pictures when I was in 6th grade. That record still can catapult me back to those days. Every story I ever heard about the guys in Rush — and I’ve heard a lot — all really portrays them as wonderful, exemplary human beings.”

Jon Butcher Axis toured with Rush in 1983 during the Signals Tour, and JBA namesake guitarist/vocalist Jon Butcher recalls that time on the road ultimately to be well spent. “To say their fans are rabid would be understatement,” Butcher observes. “I’m not sure to this day that the Axis was the perfect fit for that tour. We were the opening act, and during several dates, I was afraid their fans would kill us before Rush came on. But one thing stands out — Neil Peart. He was kind and generous to us, and watching him work from backstage was unforgettable. I will miss him.”

From the even more personal side of things, Jimmy Johnson was a childhood friend of Peart’s who served as Alex Lifeson’s guitar tech for decades before becoming the go-to gear guy for Tommy Shaw of Styx for over 20 years. Johnson, who himself sadly passed away in July 2019, once told me the secret for why he and Peart continued to remain close after all those years gone by. “We decided early in our friendship that I was never going to set up his drums, because that might be the end of our friendship,” he told me with a laugh. “That’s a wise young man there, him saying that to me.”

Finally, Richard Chycki, the Toronto-based producer/engineer responsible for seven of Rush’s studio album 5.1 mixes to date, weighed in with his own fond remembrances. “As a teen, my first exposure to Rush was 2112 — ‘Temples of Syrinx,’ to be precise,” he recalls. “It was heavy, intense, and very much unlike anything I had heard before — piercing vocals towering over the precise syncopation of a trio that truly integrated together. Suddenly, virtually every drummer I knew was clamoring for concert toms and expanding their kits to mammoth proportions — all influenced by the overwhelming prowess of one Neil Elwood Peart.

“As a guitar player and fan, I would listen to [September 1976’s live set] All the World’s a Stage and revel in the life of the album,” Chycki continues. “I hadn’t seen Rush live yet, but that album made me live it. And when Ged would introduce The Professor and the crowd exploded, I would marvel in Peart’s accuracy, musicality, and ferocity. . . every . . . single . . . time. From Fly by Night forward, Peart’s stoicism and understated presence punctuated his innate proclivities as one of the finest drummers in the world and as a deep, meaningful lyricist.”

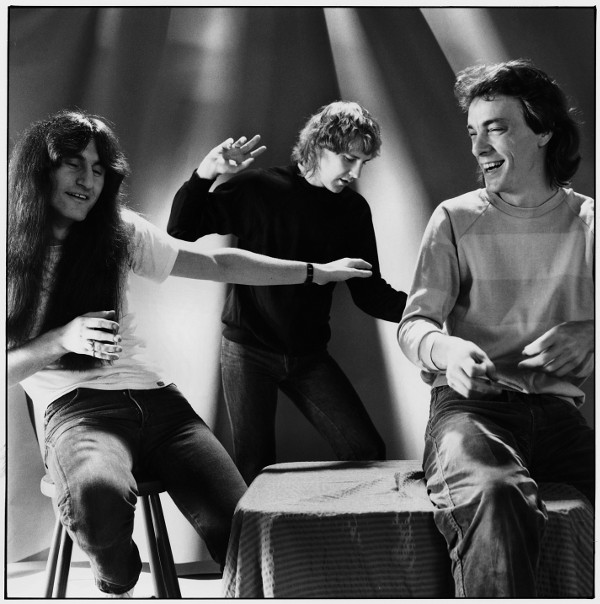

And how about more recently? “Advance to 2005, and circumstance of fate would land me in the engineer’s chair with Alex Lifeson asking me to mix the R30 DVD for Rush,” Chycki clarifies. “‘Der Trommler’ was Neil’s solo of late. My working video copy was virtually all directly overhead, and I recall being mesmerized seeing him perform at such a revealing camera angle, Peart executing the most difficult of performances with agility and power tempered by grace. He made it look so effortless!” he exclaims.

“During my tenure of recording Rush in the studio, Neil’s intensity of performance was often offset by cherubic giggling at Lifeson’s jokes, Ged’s one-liners, and my beyond horrible imitations of sitcom stars and cartoon characters. I was honored to be witness to the comradery of the true friendship the members of Rush share. Tracks we recorded like ‘Far Cry’ for Snakes & Arrows and ‘Caravan’ from Clockwork Angels are testament to Peart’s lineage as a musical yet complex drummer and lyricist. While his passing has left a cavernous void in the music community, I celebrate his humble stance as one of the finest drummers to have lived, his impassioned lyrics, and his remarkable personal bravery, resilience, and strength.” (Bravo to you for sharing all of that with us, Rich!)

But alas, all good things must in turn come to an end, and with the passing of Neil Peart, we shall indeed never see nor hear the likes of him again (or Rush themselves, for that matter). That being said, I elect to continue celebrating the sheer unyielding scope of the man’s talent, and will cherish listening to the music he and his two Canadian counterparts made together for over four decades for as long as I’m around to enjoy them myself.

In closing, I’d like to share a maxim I choose to follow at some point or another every single day, one that’s culled from a key line Peart proffered in the above-noted “Caravan,” a grandiosely heavy track on the band’s final studio album, June 2012’s Clockwork Angels: “I can’t stop thinking big, I can’t stop thinking big.”

Fare thee well, o celebrated baterista.