Flops: Fourteen Formats and Technologies That Couldn't Quite Hang On

8-TRACK TAPE (1965)

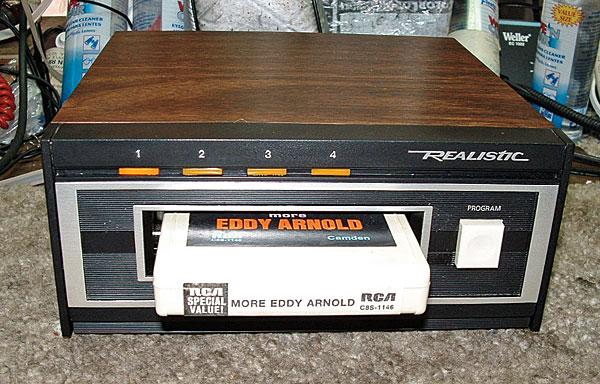

Instant access to our favorite music anytime, anywhere is a convenience we take for granted nowadays, but back in the ’60s, radio was the king of portability and the way we listened to music in the car. You were at the mercy of the DJ if you wanted to hear “Help!” or “Hang on Sloopy.” So it was a big deal when Ford introduced the optional Stereo-Sonic 8-track tape player in its 1966 Mustang, Thunderbird, and Lincoln models. Other automakers followed, and sales of prerecorded tapes boomed until the cassette finally took off in the mid- to late ’70s.

Developed by Bill Lear of Lear Jet fame, 8-track was a refined version of the short-lived 4-track cartridge introduced by car stereo pioneer/entrepreneur Earl “Madman” Muntz in the early ’60s, not long after Chrysler gave up on trying to perfect the in-car phonograph; the 4-track itself was a consumer adaptation of the endless loop cartridge introduced for broadcasters in the late ’50s. A loop of quarter-inch tape, joined by a foil splice, was spooled in a 5 x 4 x 1-inch plastic shell with an open end that was inserted into the player. The tape was divided lengthwise into eight narrow tracks to accommodate four 11.5-minute stereo segments; when the playback head passed over the foil strip, it would automatically move to the next segment.

As refined as it may have been, the 8-track format was clunky and fraught with problems. For starters, you couldn’t rewind the tape, and songs were routinely split between two program segments, meaning you might hear clunk in the middle of a favorite guitar solo as the tape head passed over the foil splice. Playback was also prone to wobbly sound and became muffled if the head was out of alignment. Sticking a matchbook cover between the deck and the edge of the tape cartridge was the high-tech fix of the day. Adding insult to injury, tape would frequently jam or break at the splice, and players had a nasty habit of turning that magnetic ribbon into mangled spaghetti—ailments caused or exacerbated by dust, dirt, and prolonged exposure to heat.

So while the 8-track enjoyed commercial success during its heyday, and even expanded beyond the car with the introduction of portable players and home recording decks, it wasn’t exactly a model of technical prowess.

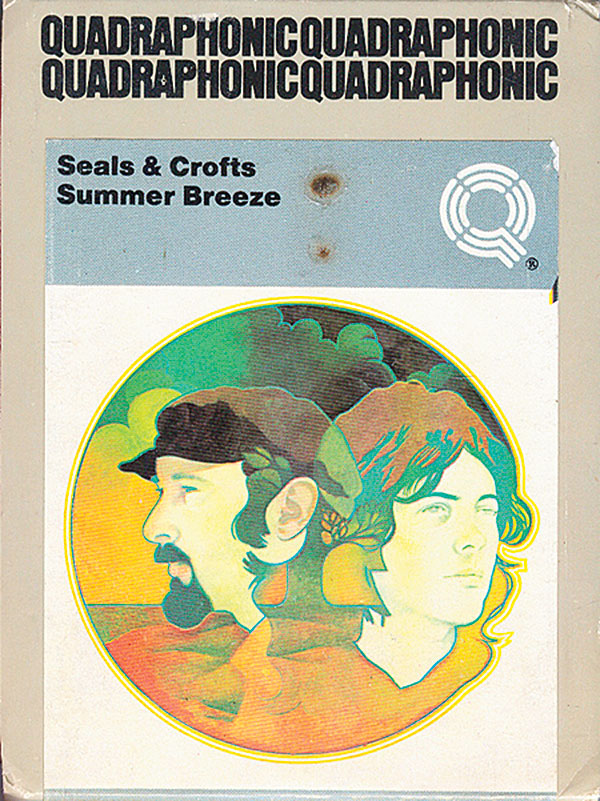

QUADRAPHONIC SOUND (1969-1970)

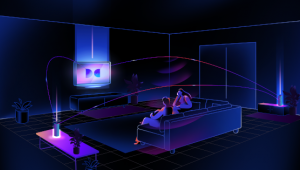

The origins of surround sound date back 70 years to a limited theatrical release of Disney’s Fantasia, which featured five-channel(!) Fantasound. But the quest for a consumer format that could deliver an enveloping listening experience at home began in the late ’60s with four-channel quadraphonic sound. Foreshadowing Dolby Pro Logic (1987) matrix and Dolby Digital (1995) discrete surround sound, quad systems endeavored to expand the soundstage by adding a second pair of speakers behind the listener—but were a good decade ahead of their time.

Seeing potential for a new revenue stream, a number of big record labels and audio companies were quick to embrace the new concept after Vanguard Records staged an impressive four-channel demo in 1969 using reel-to-reel tape. RCA rolled out its discrete-channel Q8 format for 8-track tape in 1970, which gained wide support, but when it came to the LP cash cow, the industry couldn’t agree on a standard format. The result was a debilitating war between Sansui’s QS (Quadraphonic Synthesizer) system, the CBS/Sony SQ (Stereo/Quadraphonic) format, and JVC’s compatible discrete CD-4 (aka Quadradisc) system, a complex yet theoretically better sounding format that required an outboard demodulator and a special cartridge/stylus setup to produce four discrete channels; QS and SQ were matrix formats that encoded four channels in the two stereo tracks.

While format confusion alone was enough to kill quad, other factors helped hasten its demise. The costly four-speaker/amp setup was off-putting, and the formats had a host of technical shortcomings, ranging from poorly performing matrix decoders to excessive record wear in the case of the CD-4 format. On top of that, many quad mixes were uninspired or gimmicky and channel separation usually wasn’t that great. Receivers with built-in decoders for all three formats appeared in the mid-’70s, but by that time, the quad dream had already turned into a nightmare and was fading fast.

If you want to have a little fun, hunt down a few of these recordings on CD and play them on your home theater setup in Dolby Pro Logic and other matrix-surround modes.

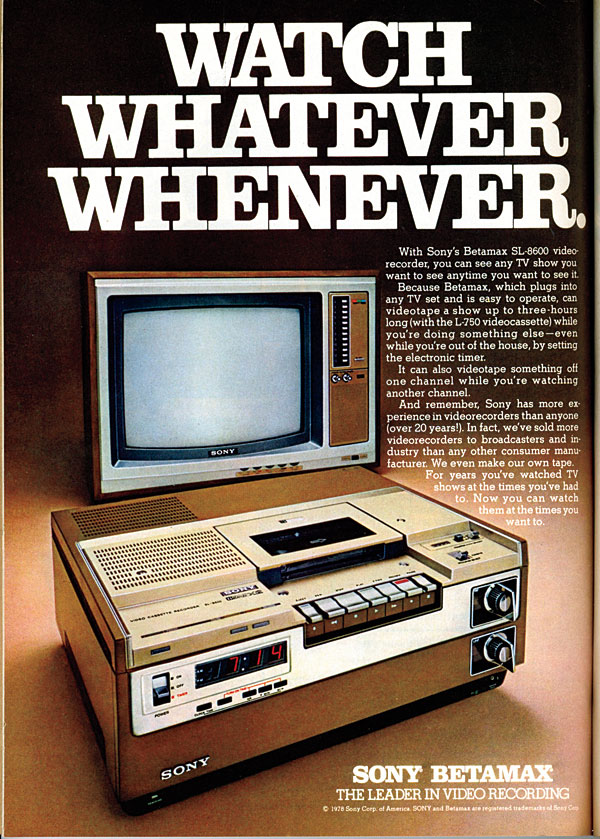

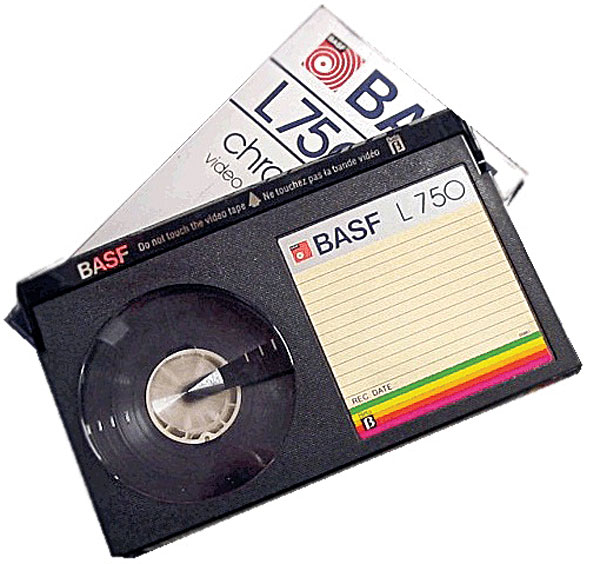

BETAMAX (1975)

Sony’s Betamax videocassette format is famous not only for losing the mother of all format wars to JVC’s VHS system, but for introducing America to the concept of time-shifting TV programs. It also became the symbol of recording rights through Sony’s seven-year court battle with Hollywood that led to the Supreme Court’s landmark 1984 decision affirming the right to record TV programs for personal use. Ironically, by the time the historic ruling was handed down, one in five American TV households already owned a videocassette recorder (VCR) and VHS was outselling Beta by a wide margin. Sony conceded defeat and started selling VHS in 1988, although Beta remained a niche format outside of the U.S. for years to come.

The downfall of Beta is a story of stubborn pride and bad decisions. Sony introduced the first consumer VCR in late 1975, nearly two years before VHS entered the market, but squandered its lead by failing to line up a critical mass of support for the format. When JVC launched the conceptually similar but slightly bulkier VHS format in 1977, it already had the support of other top brands, including TV market leader RCA. Aggressive licensing, coupled with a recording time of two hours versus Beta’s one hour, gave VHS instant market momentum. Convinced that even longer recording times were necessary for sporting events, RCA equipped its first VCR with a four-hour long-play mode, sparking a tape length/recording time war that eventually topped out at five hours for Beta and 10.6 hours (with awful picture quality) for VHS.

Other notable Beta blunders included the misguided assumption that performance alone would bring success and that consumers were willing to pay more for a better picture. While this may have been true for some enthusiasts, what the public wanted most was an affordable product with convenient features such as remote pause and a built-in event timer, which VHS offered. Although Beta was late to the party with these and other features, the format never stopped evolving and even beat VHS to the punch with high-speed picture search and other features. But in the end, technical advances such as Beta Hi-Fi and SuperBeta were too late to stop the VHS juggernaut.

Little-Known Fact 1: Betamax was predated by the short-lived Cartrivision system, an expensive console TV with a built-in videocassette recorder introduced by Cartridge Television in 1972 and sold primarily through Sears; the company racked up massive debt and declared bankruptcy a year later.

Little-Known Fact 2: In 1977, two other short-lived videocassette formats were vying for market attention: Sanyo’s V-Cord system and Panasonic’s VX system, which was marketed under the Quasar brand as The Great Time Machine.

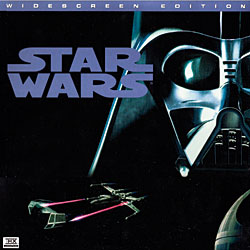

LASERDISC (1978)

The VCR was beginning to catch on and video rental stores were starting to pop up when the first laserdisc players trickled onto the scene in the late ’70s, promising a much sharper picture, stereo sound, and random access to any point on the disc with no tedious rewinding or fast-forwarding. Film buffs were agog over the high-tech video turntables, which used a laser beam to play 12-inch analog video discs, and offered enticing new controls such as slow motion, freeze-frame and still/step for frame-by-frame viewing. On the downside, laserdiscs were not recordable and had a maximum playing time of 60 minutes per side, which meant discs had to be turned over in the middle of the movie (players that could automatically play both sides were eventually offered).

The videodisc had been under development in various forms since the early ’60s but didn’t become a consumer product until late 1978 when MCA and Philips launched the DiscoVision/Magnavision optical disc system in Atlanta with an initial lineup of 72 movies, including the 1975 blockbuster Jaws. It was the first shaky step in a market rollout plagued by playback problems and a dearth of movie discs. Pioneer delivered an improved player in 1980 and relaunched the format a year later under the LaserVision/LaserDisc moniker after acquiring what was left of the failed DiscoVision venture. LaserVision was eventually dropped from the official name.

Around the same time, RCA dropped millions of dollars to launch the incompatible Capacitance Electronic Disc (CED) system it had been developing for nearly 20 years. In sharp contrast to laserdisc’s advanced laser system, the RCA SelectaVision VideoDisc player used aging phonograph stylus technology to play LP-like discs that were encased in protective sleeves and offered only VHS picture quality with mono sound. The format was obsolete from the get-go and abandoned within a few years. During the same period, JVC was demonstrating its Video High Density (VHD)—a sort of laserdisc/CED hybrid that used a stylus to electronically read a slightly smaller groove-less disc, which significantly reduced disc wear. The format was introduced in Japan in 1983 but never made it to the United States.

Around the same time, RCA dropped millions of dollars to launch the incompatible Capacitance Electronic Disc (CED) system it had been developing for nearly 20 years. In sharp contrast to laserdisc’s advanced laser system, the RCA SelectaVision VideoDisc player used aging phonograph stylus technology to play LP-like discs that were encased in protective sleeves and offered only VHS picture quality with mono sound. The format was obsolete from the get-go and abandoned within a few years. During the same period, JVC was demonstrating its Video High Density (VHD)—a sort of laserdisc/CED hybrid that used a stylus to electronically read a slightly smaller groove-less disc, which significantly reduced disc wear. The format was introduced in Japan in 1983 but never made it to the United States.

The laserdisc format evolved throughout the ’80s—eventually offering digital surround sound, widescreen presentations, and supplemental materials such as filmmaker commentaries—but was largely ignored by the masses and plodded along as a niche format before quietly fading away in the DVD era.

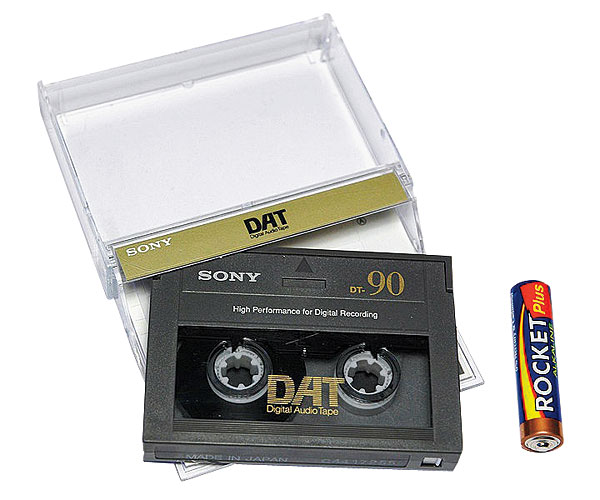

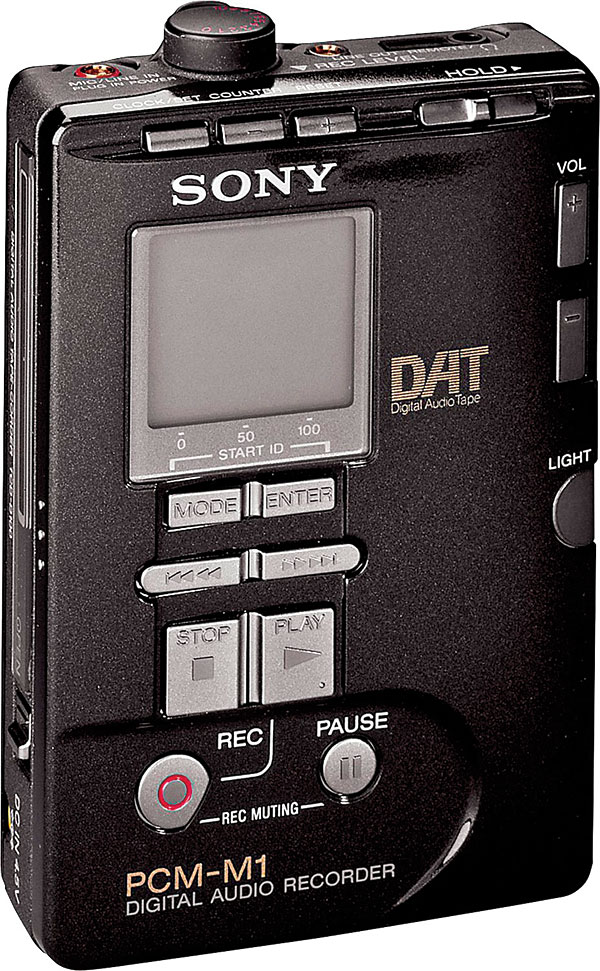

DIGITAL AUDIO RECORDING (1987-1992)

The early days of digital audio recording were tumultuous times that set the stage for the epic file-sharing battles that would come a decade later. The music industry had complained about losing revenues to home taping since the heyday of the analog cassette but went into panic mode in 1986 when Sony announced plans to launch the world’s first consumer digital audio tape (DAT) recorder as a successor to the analog tape deck. Fearing that the release of digital decks would lead to lost sales from rampant CD cloning, the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) retaliated with aggressive rhetoric—at one point likening the Japanese-dominated hardware industry to an assassin bent on destroying the music industry—and in 1987 threatened to sue the first company to sell a digital recorder.

The war was on as the RIAA lobbied vigorously for federal legislation that would restrict digital copying and compensate copyright owners for lost sales. It would be three years before DAT decks appeared on store shelves, which happened only after hardware makers agreed to equip consumer decks with the Serial Copy Management System (SCMS) that would become the cornerstone of the 1992 Audio Home Recording Act (AHRA). The law required all consumer digital audio recorders to incorporate SCMS, which permitted first-generation digital copies but prevented second-generation copying from copies; it also imposed a royalty on the hardware and blank media.

DAT was an audiophile’s dream come true, offering uncompressed near-studio-quality recording on a tape that was three-quarters the size of a standard cassette, but it never caught on with mainstream America. The format did, however, achieve moderate success in professional markets and as a data storage medium for computers. It also opened the door for two other digital formats that debuted the year AHRA became law: Philips’ Digital Compact Cassette (DCC) and Sony’s MiniDisc. Both incorporated SCMS circuitry and were among the first consumer formats to use perceptual coding technology to compress music for greater storage flexibility.

DCC was a short-lived but clever attempt at updating the familiar analog tape deck with an analog/digital hybrid that offered up to two hours of near-CD-quality digital recording on a cassette that looked like the one Philips invented in the early ’60s. DCC decks were less expensive than DAT recorders but still pricey and could play (but not record on) analog cassettes. The DCC launch was criticized for focusing on home decks and not including portable players—a mistake that limited the format’s appeal. The retro format barely caught the attention of American consumers and faded quickly.

MiniDisc was a forward-looking, magneto-optical format that stored up to 74 minutes of near-CD-quality sound on a mini CD encased in a thin, 2.7 x 2.9-inch caddy. It was positioned as a skip-free portable format that offered CD-like random access and an arsenal of easy-to-use editing features. It became popular in Japan and attracted a small, loyal base of followers here but ultimately succumbed to the onslaught of affordable CD recorders and MP3 players.