First Listen: Dolby Atmos Is "Right" At Home

And I wasn't let down. Atmos in the home environment seems to work—surprisingly well, in fact. Caveats? Yeah, there are a few worth watching out for that I'll get to later. But overall, I'll go on record that this is probably the most discernable advance in home theater sound since the introduction of lossless digital audio in the Dolby TrueHD and DTS-HD Master Audio formats on Blu-ray. And it's one that leaves all the pre-existing height- and width-channel surround formats— including Dolby Pro Logic IIz and DTS Neo:X—in the dust. Finally, this may be one that will truly make it worth the trouble of adding those extra speakers. Maybe...

What is Atmos?

If you've not been exposed to Atmos or don't know what it is, don't feel bad. The system only debuted with the release of the Disney film Brave in 2012, and Dolby currently lists only about 130 or so theaters in the continental U.S. on its Atmos locator. They tend to be mostly in high-population regions, and even where Atmos theaters exist, the exhibitors haven't always done a great job of promoting them. At the AMC theaters that feature it, for example, it's lumped in as one of the technologies being offered in some of their ETX (Enhanced Theater Experience) auditoriums; if you look for the word "Atmos" in their movie listings, you won't find it.

For those unfamiliar, Atmos is an object-based audio mixing system that allows movie sound engineers to place objects essentially anywhere inside of a dome-shaped envelope above the audience. Recorded "objects"—whether a human voice reciting dialog, the sound of a traveling helicopter prop, an insect in a tree in the forest, or a foley effect of breaking glass—are dropped inside a graphic representation of the listening space displayed on a desktop monitor, moved around as desired, and assigned metadata that describes the object and its position at any given moment. This data becomes a permanent part of the soundtrack. The Atmos decoder in the theater knows the speaker/channel configuration available to it at that installation; as many as 64 separate speaker channels can be addressed by the processor. When the soundtrack is played back, it uses the metadata to automatically map the speaker output levels in real time to position each sound as close as possible to where the mixing engineer intended.

This is already decidedly different than traditional "channel-based" mixing, wherein a movie might be mixed with a 7.1-channel soundtrack in which every sound gets manually placed, or panned across different channels on the mixing board to create a sense of movement. The 7.1-channel soundtrack must then be arduously adapted to 5.1-channel and stereo mixes for smaller systems. That work is essentially eliminated with Atmos. But what's key to the Atmos theatrical experience is the addition of individually addressable ceiling speakers, typically found in left/right pairs that correspond to the position of the surround speakers mounted on the theater's side walls. It's the ceiling speakers, and the way in which they're discretely controlled by the Atmos soundtrack, that allow for a more realistic soundfield than has been possible even with a traditional 7.1-channel setup with side-wall and back-wall surrounds, or any of those artificially-derived adaptations that add height and width speakers to 7.1 and 5.1 channel soundtracks. Instead of ambient sounds tending to hug the boundaries of the room where the surround speakers have been traditionally located, they can be made to come from directly overhead for any seat in the audience.

All of that said, my impressions of Atmos in the theater have been largely dependent on how the film's creators chose to use the available tools. The effect can be subtle and simply create a more convincing ambience for special effects, as was done in the Hobbit films. Or, it can be more pronounced, as in Life of Pi. While Pi made superb use of the overhead speakers to recreate the feel of wild ocean storms, the soundtrack also used the ceiling speakers at times to place elements of the music score overhead while the rest of the score played across the front speaker array, allowing for a greatly expanded and spacious soundstage. With either approach, though, you're going to come away with a fresh and more engaging movie experience.

Atmos At Home

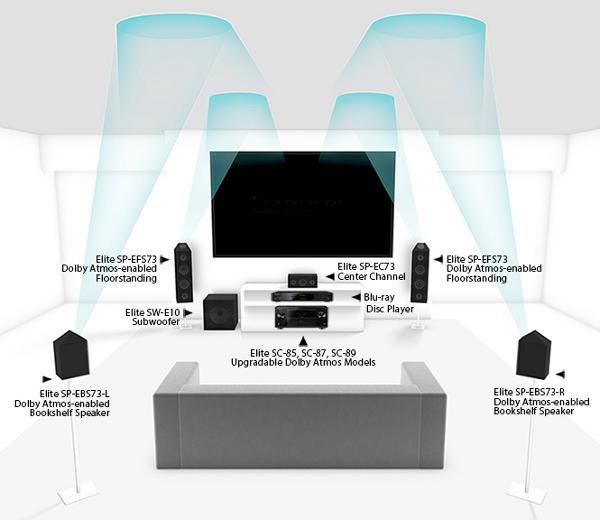

About 200 movies have now been mixed in Atmos. Making use of those soundtracks in home theaters means adding what most often would be four additional speakers to convey the the ceiling-speaker information. You need a source component that can deliver an Atmos bitstream, an AVR that can decode the bitstream and drive power to the extra speakers, and the speakers themselves.

For soundtrack delivery, Dolby says any existing Blu-ray player should suffice, and I noticed the demo discs being used for the CE Week demos offered Atmos menu options for both Dolby TrueHD and Dolby Digital Plus soundtracks; the latter could potentially be used for streaming content. For the decoding hardware, Atmos firmware upgrades for pre-announced AVRs or brand new Atmos-enabled AVRs are planned by several manufacturers, including Onkyo and sister brand Integra, Denon and sister brand Marantz, Pioneer and Yamaha. Higher-end 9.1-channel models are an obvious fit because they provide the amplifier power to drive four additional speakers in what Dolby is designating a "5.1.4-channel" system to include the traditional five surround channels, the subwoofer, and four ceiling speakers.

More Dolby Atmos News:

Dolby Atmos Movie-Theater-Sound Technology Heading to Home Gear

Pioneer Showcases Dolby Atmos-Enabled Receivers and Speakers