Defining the Internet of Things

You can’t see the Internet of Things but, trust me, it’s there — and growing rapidly as every imaginable kind of “thing” becomes (or at least tries to become) net savvy. But what exactly does IoT mean? And if we move beyond the quaint Jetson-esque vision of the future, what are IoT’s real-world implications? To get a handle on where our increasingly interconnected world is heading, we tracked down Dave Evans, former chief futurist for Cisco and co-founder of the Silicon Valley IoT startup, Stringify. Strap on your seat belt and prepare for an exciting ride into the future.

S&V: Let’s start with the basics. We’ve been hearing a lot about IoT — the Internet of Things — over the past couple of years. It so all-encompassing. How do you define it?

Dave Evans: In the simplest sense, the Internet of Things is about everyday objects connecting to the Internet — “things” such as your coffee pot, your lights, your car, wearable devices, on and on. Historically speaking, computers and networking devices were primarily connected to the Internet, but today billions of other types of things are getting connected. They connect because there is some value in doing so. For example, your wearable might connect to a service for uploading fitness stats so you can track your progress, compete with others, or get feedback on how to improve your workouts. In a more technical sense, this is about devices (“things”) with embedded technology and sensors connecting to the Internet and using standard protocols to exchange information.

S&V: Let’s break things down a bit if we can. What are the key areas of IoT?

Evans: The key areas are the “things” themselves, the embedded technology and sensors within these things, the Internet, the APIs (application programming interfaces), the cloud, and new business models.

What’s most interesting is that the types of things we can connect to the Internet are no longer confined to computers and other traditional devices.

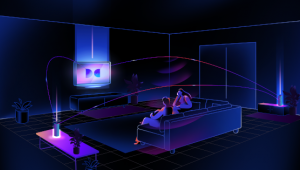

What’s most interesting is that the types of things we can connect to the Internet are no longer confined to computers and other traditional devices. They are everyday objects that expand their capability and value because of their connections — not just to the Internet but to other things as well, which means they can work as a system. Imagine if your smart home could automatically turn off the lights, lock the front door, adjust the temperature, and set the alarm system when it’s time to go to bed. This is a much better experience than going to each thing individually and adjusting it.The embedded technology and sensors within these things refers to the innate capabilities of the devices themselves. Thanks to Moore's law, technology that was once impossible, is now commonplace and embedded in everyday things. The tiny computer inside of a smart thermostat has more computing power than the entire planet had a few decades ago. Thanks to MEMS technology (Micro-Electro-Mechanical Systems — miniaturized mechanical and electro-mechanical elements), sensors have become smaller and cheaper. Sensors that track temperature, humidity, vibration, acceleration, location, and more are now easy to place into everyday things, giving those things the ability to sense the world in ways that were previously impossible.

More and more companies are exposing their services through open APIs, which provide standardized ways in which one can access a given service. For example, it is now trivial for your smart thermostat to connect to a weather service via an API to determine how best to set itself. Your smart and connected irrigation system can now easily connect to that same service to determine whether or not to run the sprinklers that day.

The cloud helps to hide the complexities of the infrastructure behind these services, so developers can now focus on accessing services, without worrying about the supporting infrastructure.

And, of course, all of this leads to new business models. As the world becomes more open, more connected, and more aware thanks to billions of sensors, more companies can offer access to these services, which creates entirely new opportunities. This also lowers the barriers to entry so anyone with a great idea can change the world with IoT.

While the things are of great value, one could argue that it’s really the intelligence in the cloud that has the greater value.

S&V: Of these key areas, which are most compelling right now? And — broadly speaking — how and where does home entertainment fit in?Evans: When we talk about the Internet of things, we often focus on the things themselves. While the things are of great value, one could argue that it’s really the intelligence in the cloud that has the greater value. The software world is opening up through extensive use of APIs. This essentially means that a “dumb” thing can now become an “intelligent” thing, simply by having a connection and tapping into the vast knowledge that is in the cloud.

This has huge implications for home entertainment. Obviously, we have seen increased access to Internet-based services such as Netflix, but this is very much the beginning. Television — with your permission — will watch you while you watch it and learn what you like and what you dislike, perhaps by observing your facial expressions while you watch a show. This information will be analyzed and fed through machine learning algorithms to intelligently tailor content that is best suited for you. One could even imagine smart programming that recognizes children are also watching TV and automatically avoids inappropriate shows.

But it goes beyond smart televisions. Information about the shows you are watching could also be automatically fed to other nearby smart devices. For example, getting statistics on your favorite sports team sent to your iPad while you’re watching the game or getting information on where to buy a jacket or dress an actor or actress is wearing in the movie you’re watching.

S&V: Voice control is all the rage today with Alexa, Siri, Google Assistant, and other virtual assistants — vying to dominate the space. The thing I’ve noticed is how quickly the accuracy of speech recognition is improving. Will voice-control be the dominant means of control for home entertainment and smart-home applications in the near term and in the longer term — say, 10 years out? Or will it gravitate toward something else such as gesture control or even “mind control”?

Evans: Ultimately this is all about technology adapting to us. Since the inception of technology, we have always had to adapt to it to learn how to use a new interface, a new device, whatever. But now, something profound is happening: technology is adapting to us. A voice command, a gesture, an emotion, and even a thought, in some cases.

Voice will be one of the dominant ways in which we interact with technology, but certainly not the only one.

Voice will be one of the dominant ways in which we interact with technology, but certainly not the only one. There are times when voice is simply not appropriate. In a noisy room, for example, a gesture might be a better solution for turning down the lights than a voice command.Control of smart devices will be active and passive. An example of active control is when you walk up to a thermostat and adjust it manually. An example of passive control is when your thermostat detects a change in weather and automatically adjusts itself.

This will only become more advanced over time. Today, we are very much in the active control phase of home automation — meaning, most of the time, we actively control our smart devices. We utter a voice command to control the lights, lock the front door, or set the temperature. Over time, smart homes will evolve into intelligent homes that learn our habits and make adjustments automatically. Much like how your email system over time learns the difference between normal email and junk email, expect to see more and more learning abilities in the smart home as it evolves.