CES at 50: From Humble Origins to Global Showcase

Regardless of your view of Sgt. Pepper, it certainly holds up better than the then cutting-edge but now delightfully quaint AV gear introduced at the first Consumer Electronics Show (CES), also held 50 years ago this week, June 25–28, in New York City.

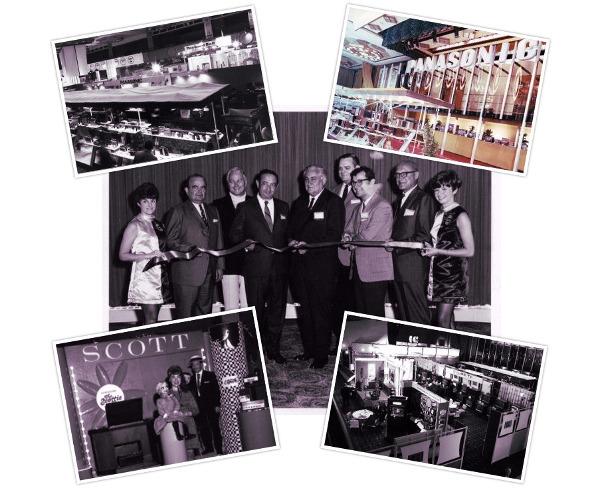

Booths at four Manhattan hotels, primarily the midtown Hilton on Sixth Avenue and the Americana—now the Sheraton—around the block on Seventh Avenue, were filled with primarily four categories of products: TVs, record players, radios, and an essentially new class of products: Audiotape players for both the home and—just barely emerging in 1967—the car.

While most of the products displayed at the first CES would now qualify as historical curiosities, CES itself has become synonymous with innovation, the global gathering to see and hear the future.

But why, considering "consumer electronics" had been around since the birth of commercial radio in 1920, was there not some sort of AV equipment showcase before 1967?

CES Origins

The short answer to that question is, there was. In 1924, several companies in the nascent radio business banded together to form the Radio Manufacturers Association (RMA), which ran annual open-to-the-public radio exhibitions around the county until the mid-1930s. These likely ended as a result of the Depression and then World War II.

After the war, RMA shifted its focus to keep up with technological changes, becoming the RTMA (Radio and Television Manufacturers Association) in 1950, then the RETMA (Radio-Electronics Television Manufacturers Association) in 1953. In 1957, accounting for the dramatic rise in government and industrial electronics, RETMA converted itself into the EIA (Electronics Industries Association). To represent the 20 percent of sales constituting home electronics, a Consumer Products Division within EIA was created.

With no industry-specific trade venue, consumer electronics vendors displayed their wares at a variety of other trade shows, most only tangentially associated with TV, phonographs, and records. Primary among these was the Music Show, run by the National Association of Music Merchants (NAMM)—an organization for the musical instrument business.

By the mid-1960s, however, companies such as RCA and Zenith began to dwarf not only their fife-and-drum-selling neighbors, but the entire musical instrument industry. A variety of CE companies lobbied NAMM for a more representative presence at the Music Show, to no avail. So in mid-1966, EIA's Consumer Products Division staff VP Jack Wayman convinced the EIA board to sponsor an industry-specific consumer electronics show.

Ignoring the Young

While establishing CES was prescient, the assembled vendors were less concerned about addressing the industry's most lucrative future market. We all know how tectonic the mid-1960s were. One often overlooked shift lost amongst the long hair, short skirts, civil rights marches, political assassinations, war protests, sex, drugs and rock n' roll culture-change headlines, however, was the more pedantic coming of age of a new consumerism among the humungous post-war Baby Boom generation.

With the exception of transistor radios and "picnic" players (small, portable record players that teens would stack a pile of 45 RPM singles on for party play), the growing importance of the 15-to-24-year-old demographic had been largely ignored by conservative middle-aged male electronics executives. As such, it’s doubtful that any rock records were spinning on turntables as hi-fi audition material at that first CES, despite the revolutionary Sgt. Pepper and the breakthrough Monterey Pop Festival that had concluded only the week before. Classical music and jazz were the chosen soundtrack for CES 1967; rock ‘n' roll was considered kids' music by the mainstream music reproduction suppliers, unworthy of playback on their sophisticated gear. (They weren't far off in thinking rock ‘n' roll lacked technical sophistication; The Beatles worked primarily on a mono version of Sgt. Pepper, with the original stereo mix a mere afterthought. But I digress.)

At a Youth Market panel presented at CES that year, Philco-Ford Consumer Electronics Division VP and GM Armin E. Allen sarcastically mocked that while youth may "defeat poverty, wipe out ignorance, and overcome injustice…any manufacturer or retailer who becomes enchanted by the tremendous number of people in the 15 to 24 age bracket and gives this segment of the population his undivided attention is making a mistake."

Which may explain why there's no Philco-Ford any more, and why the company ignored a new booming technology being copiously consumed by kids—tape.

First Format War

By 1967, the familiar wooden credenza-type living-room phonograph consoles were fading from fashion in favor of tabletop turntables and the aforementioned portable picnic players. But thanks to the discovery and development of audiotape and the booming commercialization of the transistor, personal music playback could finally make it to the car.

A reel-to-reel tape deck was a key part of a hi-fi enthusiast's solid-state home stereo rig, but it was hardly a mainstream product and not portable at all. But in 1964, the 8-track tape—or Stereo 8—loop cartridge format exploded into the public consciousness. By 1967, nearly every major car maker offered a factory-installed 8-track option.

In mid-1966, two other tape options were unveiled: Philips' two-track compact cassette and MGM's PlayTape, a 1/8-inch two-track loop cartridge that held 24 minutes of music. PlayTape came in five colored flavors: red for a two-song "single" ($1), black for four-track EPs ($1.49), blue for children's fare ($1.00-1.50), white for eight tunes ($2.98), and gray for talk and educational material ($1.00-1.50).

|

1967’s landmark Beatles album on a super rare and short-lived 2-track tape cartridge. |

At that first CES, all three tape formats fought for prominence among both hardware vendors as well as record labels—the first format war. All the loop formats would be referred to as "CARtridge" to stress their automotive focus, but there were plenty of home decks and even changers.

Not fully certain which format would prevail, many top record releases—including Sgt. Pepper—were sold in up to six different media: vinyl, reel-to-reel tape, compact cassette, 4-track cartridge, Stereo 8, and a four-song PlayTape version.

Of the 117 exhibitors at the first CES, 43 hawked some sort of tape equipment, including Capitol Records, The Beatles' U.S. label, which sold its own branded 8-track decks. By the end of 1967, audiotape hardware sales were estimated at 12 million units, more than twice the number of record players sold.

Compact cassette's unique recording capability ultimately would not only prove decisive, but created a whole new "mixtape" culture and laid the groundwork for establishing legal home recording rights in the Betamax case nearly 20 years later.

TV Technology Transition

While music was undergoing a radical shift in both what we listened to and how, TV seemed a bit more stuck in place. For instance, the top 10 TV shows on the three major networks, ABC, CBS, and NBC, continued to be alternatively staid, safe, and silly—Bonanza, The Red Skelton Hour, The Andy Griffith Show, The Lucy Show, The Jackie Gleason Show, Green Acres, Daktari, Bewitched, The Beverly Hillbillies, and Gomer Pyle. Only the hip Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour hinted at the degree of edginess that would infiltrate network TV in the 1970s.

But one on-air advance was obvious. Finally, 13 years after RCA muscled through its NTSC color standard, 1966-67 was the first TV season in which all prime-time programs were broadcast in color. As a result, color TV vendors led by RCA, Zenith, and Admiral dropped prices on color sets 5 to 10 percent that summer.

Color TVs were still expensive in 1967, even more so than 4K sets today. Screen sizes ranged up to 23 inches and cost between $500 and $900—around $3,600 to $6,600 in 2017 dollars. Despite their lofty prices, color models started outselling monochrome sets in the U.S. two years earlier, and color would account for nearly 75 percent of all sets sold by the end of 1967.

Aside from the color, the world was expanding thanks to TV technology. Coincidentally, Sunday night, June 25, the evening of the first day of the CES, was the global broadcast of "Our World," the first program beamed live around the world via satellite. Consisting of vignettes from 14 countries, the show was capped by, yes, The Beatles, representing Britain with the premier of a song written specifically for "Our World"&mash;" "All You Need is Love."

Perhaps more importantly to the industry, Japanese TV manufacturers such as Sony, Panasonic, Toshiba, Hitachi, and Sharp, heretofore known primarily for budget (OK, cheap) goods, displayed their first U.S. color TVs at CES and were in the midst of establishing their first American subsidiaries, which would lead to their dominance less than two decades later.

Hardware-wise, the innards of all new TVs were now solid state rather than driven by vacuum tubes (the screens, of course, were all of the CRT, cathode-ray tube variety). This finally allowed for faster start-up (such as the touted "Instant Play" feature on Admiral models), automatic fine-tuning that reduced the amount of antenna jiggling, and for some shrinkage of cabinet size. CES saw the first affordable battery-powered "portable" color TVs—weighing up to 45 pounds and mostly designed to be rolled around on an optional cart—costing between $200 and $330, $1,500 to $2,400 in today's currency.

If color models were too hefty, there also were black-and-white portables with screens as small as 1 inch and weighing as little as 5.5 pounds, including batteries.

Cause or Effect?

In all, an estimated 17,500 trade executives attended that first CES, a tenth of CES 2017's record attendance that practically overwhelmed Las Vegas.

With 50 years of hindsight, we can wonder: How much did having its own showcase influence the explosive growth of consumer technology over the subsequent half-century? That's an unanswerable chicken-egg conundrum. But it's undeniable that the pace of home electronics development certainly accelerated, coincidentally or not, after that first show.

From just those first four product categories—TV, phonograph, radios and tape decks—the CE landscape burst forth with technology unimaginable in 1967: the personal computer, the VCR, the camcorder, cartridge and then CD video games, the CD, the cell phone, the internet, satellite TV, satellite radio, GPS, the DVD, big-screen projection and then flat-screen TV, Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, the digital camera, HDTV, the smartphone, flash memory, Blu-ray, tablet PCs, 3D printers, 4K UHD, drones, smart home, autonomous vehicles…

So, while the products at that first CES haven't aged as well as Sgt. Pepper, CES itself continues to get better all the time.