The Making of All Things Must Pass Page 5

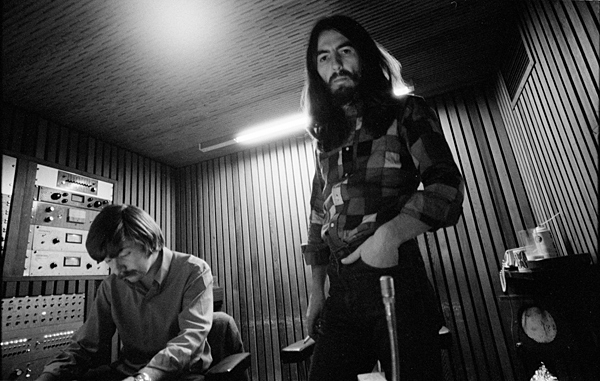

Leckie didn't have the advantage of being able to see the goings on on the studio floor, as he had in Studio 3, the tape machines being placed in a separate room from the control room in No. 2. "It was all dark and smoky down there anyway," he laughs.

Only a single song was recorded, the enormous "Awaiting On You All." The song has George with the Dominos, some great Eric Clapton slide receiving a boatload of reverb. The entire song tracked live, with Whitlock and an unknown player providing organ and piano, respectively and George offering a guide vocal. Take 25 was the master, onto which brass and percussion were added, and Eric overdubbed his harmony slide part.

Work resumed after a 3-day weekend, on Tuesday June 30, with work continuing the following day for another pass at "Run of the Mill" and a whole other version of "Art of Dying," the master being Take 26, Clapton delivering a blistering wah-wah opening lead, and Jim Gordon and Carl Radle driving the powerful rhythm, accompanied by Whitlock's Hammond. Leckie recalls, "We had been in Studio 2, and when we came back to Studio 3, there was a lot of energy for everyone. And we did those two songs, and it was quite an intense session." "Run of the Mill, after 61 takes, finally found its master, complete with live brass, but not before getting the full electric treatment, as can be heard on Take 36 (bonus track/outtake).

Studio visitors came and went throughout the sessions, and on this day, none other than a young Phil Collins popped in, wanting to contribute to the song. "I vaguely remember, late night, someone saying, 'Oh, this drummer has turned up,' and me and Phil McDonald going, 'Oh, God – we've got another drummer??' They answered, 'No, no, he's just gonna play congas." As a joke – not certain if true – Harrison later overdubbed some congas onto a mix, with the congas turned up quite loud, Leckie states. "He said, 'There you go – there's the congas.'"

The rest of the week was spent doing overdubs in Studio 3—and, finally the final take of "What Is Life" on Friday July 3 – take 42, onto which Jim Price and Bobby Keys double-tracked their live horns. The lads also tracked a number of jams, a few even on 8-track this time, including one of "Get Back" on July 1, of all things.

But by the weekend, George realized that his mother, Louise, was dying, and let his Domino friends use the studio for one last pass at "Tell The Truth," its master finally captured, sans George, on Monday July 6. The following day, George's mother passed.

It would not be until later in the month, Monday July 27 thru Wednesday August 12, that he would return to the studio for additional overdubs, in both Studios 2 and 3. But just before, on Saturday July 25, after being greeted once again, by the cheerful "Apple Scruffs" outside the studio, he decided to record a song in tribute to the fans, one by that very name, in Studio 3.

Recorded without Spector in attendance, and with John Barrett operating tape, he did a simple acoustic song, tapping his foot on the metal stool on which he was sitting. accompanied by Mal Evans tap his foot to keep time (with no drums). Also played live was George playing harmonica, something he had rarely ever done.

On Monday July 27, Phil McDonald did 8-track to 8-track "bounces" – submixes from one 8-track tape machine, containing the original masters, to another 8-track machine, onto which he combined some tracks, to make room for overdubs he and George would pursue in the following days. These included "Awaiting On You All," "What Is Life," "Isn't It a Pity (Version 2), "All Things Must Pass," "Let It Down" and "Art of Dying." It was during this step that reverb was added to some of the stereo guitar tracks, as well as effects like ADT to George's main guitar riff on "What Is Life."

-2.jpg)

George's lead and background vocals were finally added to "Awaiting On You All." Also done then, though, were John Barham's string arrangements, recorded both in August at Abbey Road (for "Let It Down") and, the following month, at Trident Studios, where more overdubbing would take place.

Pete Frampton also returned to add more acoustics, alongside George, on a number of tracks. "George called up and said, 'Pete, Phil wants more acoustics.' I said, 'You're kidding me.' He said, 'I know.' So there were the two of us, sitting in front of the glass, and they'd pull up tracks, some I had played on before, and say, 'Well, George, we need more acoustics on this one.' It might have been 10 of them. Just the two of us, and then we'd double-track it."

Barham wrote beautiful—and always appropriate – string/horn arrangements for five songs on the set, based on both George's suggestions and the ones he had made when George played him the songs at Friar Park five months earlier.

The recordings featured 18 players, typically two songs in each 3-hour session. For "Isn't It a Pity," he notes that "the acoustic guitar ensemble figure sounds much like a lot of recent minimalist music. And the timbre is quite metallic and mechanical sounding. So when I arranged the strings, I went for an opposite timbre, that would add warmth and a soft edge," also adding a background choir that, with the busy drums, builds up the kind of symphonic effect associated with Spector's productions.

"What is Life" received strings which contrasted "a very busy track," its wall of sound, "until the fade, when the strings play a rhythmic figure." "Let It Down" features strings, as does "Beware of Darkness," which has a simple, gentle string accompaniment. The title track, "All Things Must Pass," he notes, "is one of my favorite songs. There is a spiritual quality to it. When George begins to sing, he is high and flying. The strings enter in their high register, which is unusual, when compared to the other songs."

After attempting to add overdubbed parts onto the 8-track tape at Abbey Road, and finding it cumbersome, requiring bouncing down tracks frequently, George decided to bring his recordings to another Abbey Road alumnus, Ken Scott, by then working at Trident Studios. Trident, by that time, had 16-track tape machines, allowing Scott to simply copy the 8 tracks from the Abbey Road reels onto tracks 1 thru 8 on his 2-inch tapes (which he did on September 2), with another 8 available for additional work. He was assisted by Dave Corlett, who served in the same role Leckie did for McDonald, working from Wednesday September 2 thru Saturday September 12.

The majority of the overdubs involved both lead vocals and background vocals, as well as miscellaneous guitar parts, on 12 of the 19 songs. Besides adding his pair of slide guitar parts to "My Sweet Lord," Scott notes, regarding the background vocals, "George did them all. We'd record a few background vocal parts, and he'd add another one, as I was bouncing those down" – mixing multiple tracks of vocal down to a single track, available elsewhere on the tape, to allow additional parts to be recorded on those previous tape tracks. "Then I'd bounce those ones across with the next harmony. And we just kept on going like that, recording on multiple tracks and bouncing down, mixing every time." And contrary to stories you might have heard otherwise, George's beloved Hare Krishna friends do not sing on the recording. "They brought him food," Scott states.

"What Is Life" received a curious overdub. Besides the strings, some guitar fills, and George's lead and backing vocals, "We attempted to record more brass. There was a line that George wanted. We first tried it with Bobby Keys and Jim Price, but it didn't feel right. So George thought it might feel better if we used classical musicians. So we had a piccolo trumpet and an oboe, and it felt just as bad. So it was never actually used in the mix, but it's still on the multitrack." A mix including those horns, and without vocals, was issued in 2001, for the 30th anniversary reissue.

Mixing the album took place at both Abbey Road in early October with McDonald, and at Trident with Scott, from Saturday October 10 thru Saturday October 17, both with George and Spector present at both, along with Mal Evans, Kevin Harrington, and, occasionally, Pete Bennett, from Capitol Records in the States. McDonald mixed the 8-track recordings that hadn't required additional overdubs at Trident, and Scott mixing the songs which had been transferred to 16-track.

At Abbey Road, McDonald and Leckie worked from Tuesday October 6 thru Friday October 9, in a dedicated mix room, Room 4, as well as in the control room in Studio 3, where they could take advantage of the Varispeed setups, for tape wobble, phasing and other tape effects, as were done on "Isn't It a Pity (Version 2)" and "I Dig Love," with its tape echo. Other tracks mixed by McDonald included "I'd Have You Anytime," "If Not For You," Run of the Mill," "Awaiting On You All," "Apple Scruffs," "Ballad of Sir Frankie Crisp" and "Art of Dying." The remainder were mixed by Scott, finishing on Saturday October 17.

Leckie recalls two important visitors who popped into Room 4 on Wednesday October 7, where he and McDonald were working. "John and Yoko walked in and said, 'How ya doing?'" Though John had started working in Studio 3 with McDonald and Leckie for the first sessions for John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band, Richard Lush and Andy Stevens had taken over, while Phil and John were mixing with George. But on this day, Leckie notes, "They didn't stay long. But they said to Phil McDonald, who they knew from Abbey Road, and to me, 'I'm working on my new album, and I want you two to do it, as soon you're done with this one.' That was a big moment."

Lennon's timing couldn't be better. He had been working in No. 3 from about 2:30pm until 10pm, just recording some jams and an acoustic guitar take on his song, "God." With John gone for the night, George could now tackle one last piece of recording in the studio, one which Yoko had secretly asked him to do. Two days later was John's 30th birthday, so she asked George to record some kind of special song to celebrate.

"George and Phil McDonald went upstairs to the tape library and went through the card files," Leckie recalls, "and they found tapes of fairground organs playing tunes," eventually settling on a version of Cliff Richards's "Congratulations." "I remember getting the tape from the tape library and we put that on a piece of 8-track. "I then wobbled it, phased it, using the Varispeed." And then, in a session which ran from midnight to 4:30am, George added some "mad slide guitar, and then we all got out and sung on it. There's me singing, everyone. Anyone that was around would go out and do, 'It's Johnny's birthday, it's Johnny's birthday. . . ,'"

double-tracking their chant. The gang included George, Spector, Eddie Klein, Kevin Harrington – everyone except McDonald. "Phil wouldn't do it. He's a bit too serious for that." McDonald promptly mixed it, and that mix was put on a plastic reel and given to Mal Evans to pass along to Yoko, and it was indeed given to John on his birthday. And, to top things off, it was added to Apple Jam, when McDonald edited the jams down to size and assembled the two sides. [A new mix of the song, minus the calliope, appears as a bonus track on the new set.]

That same day, George also recorded himself singing 5 takes of a song called "Mama Don't You Cry For Me" – which he would record formally in 1976, as "Woman Don't You Cry For Me," for his Thirty-Three & 1/3 album.

Though some documentation notes that the album was mastered at Trident, neither Ken Scott nor Trident's mastering engineer at the time, Ray Staff, recall that occurring. According to George Peckham, Apple Studios' own in-house mastering engineer, "George had me master All Things Must Pass at Apple, and was very happy with my cut." Straight copies of the album side reels, were sent to territories for pressing, accompanied by Peckham's mastering notes, to ensure a uniform sound around the world – which Peckham was given authority to reject, if they did not comply.

For the U.S., Harrison brought the album reels himself on October 28, followed by Peckham, to MediaSound Studios NYC, as requested by Allen Klein. Peckham supervised veteran cutting engineer Dominick Romeo, who cut the album to his specs – though, he notes, "He didn't like a younger man to be in charge, and I caught him trying to change the settings I had brought with me." There was another issue, something many fans have noted over the years regarding some first U.S. first pressings – a noticeable speed variance on some album sides. "They had a problem with their lathe turntable drive," most likely a Scully, which is belt-driven. "It was appalling, and I told their maintenance man it was slipping, and that he needed to repair it, so that we could recut all of the dodgy ones." Though Peckham asked Al Steckler, who ran U.S. Apple Records, to try to recall those sets pressed from the bad lacquers, apparently some still made it into stores.

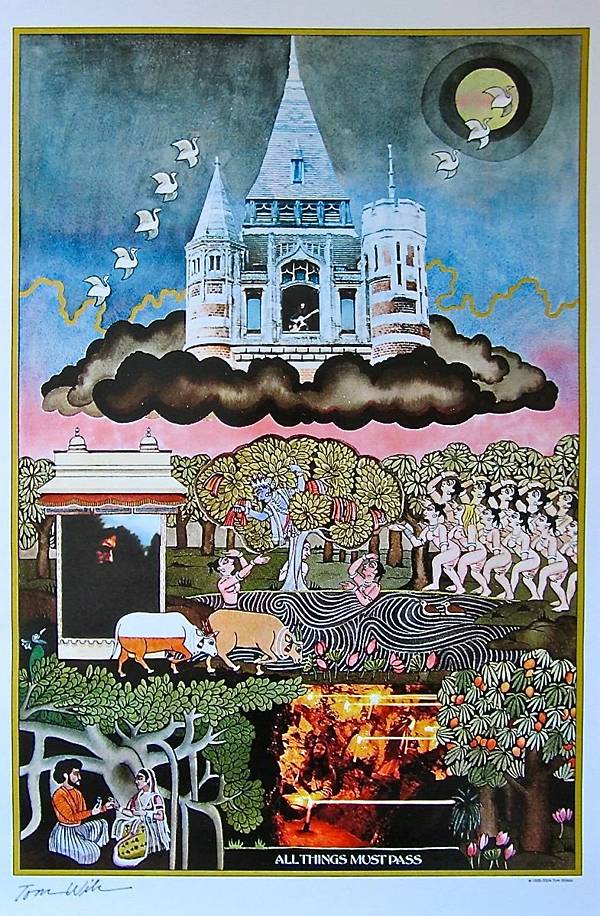

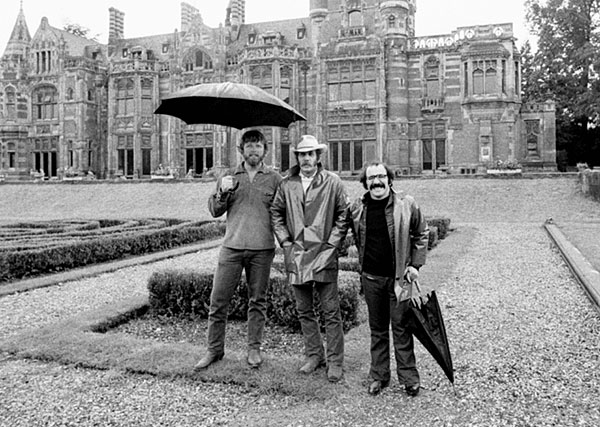

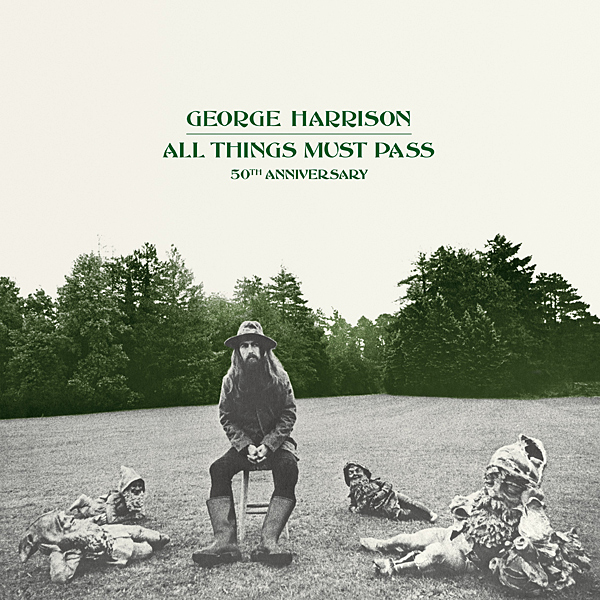

The sleeve was designed by Tom Wilkes, the former head of A & M's art department, who would design covers for many of Harrison's albums in the 70s, featuring photos by Barry Feinstein, taken at Friar Park. Most famous, of course, is the cover photo, with George sitting surrounded by a handful of his garden gnome statues (a replica set of which can be found in the "Uber" deluxe version of the 50th anniversary reissue). "He and Spector knew I did conceptual packages," said the designer, who died in 2009. "He brought us over, and we found these gnomes laying around the grounds, so we just set it up. And he came out in his Wellingtons [tall boots], and we shot it!" Adds his daughter, Katherine, "My father told me that he four gnomes are supposed to represent the four Beatles. And the gnome that's positioned away from the other three represented George."

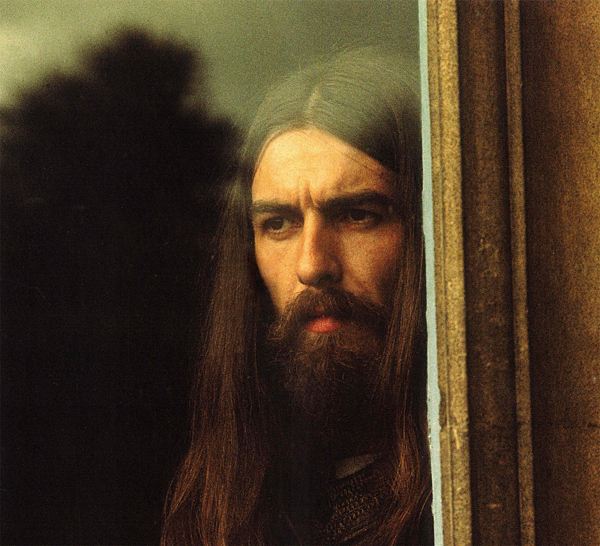

The package included a poster, featuring a beautiful portrait of George, taken by Feinstein in a window in Friar Park. But there was also to have been a second – a wonderful collage full of Indian imagery, hand-painted by Wilkes, and featuring a few photographs. But Harrison passed on it (it is reproduced here, courtesy of the Wilkes Estate). Wilkes also painted a jam jar, which appears as the label backdrop image for the Apple Jam LP labels.

Remixing – 50th Anniversary

Ken Scott notes that, in 2001, he and Harrison briefly considering remixing All Things Must Pass, doing a "de-Spectorized" version, leaving out the excessive reverb and some effects present on the original. When it came time to create a new mix for the new 50th anniversary release, George's son, Dhani, and engineer Paul Hicks, who also has been remixing the John Lennon catalog, considered a similar approach, also only briefly.

"We actually mixed it a few times," Hicks explains. "The first time, I did the slightly more traditional way that we've done it, where I matched the mix to what it was," then thinking about which elements perhaps should be brought out more than in the original, as he did with the Lennon Gimme Some Truth package, raising, for example, George's vocal more. "It sounded very similar to the original, but with a little bit more clarity."

A second pass was taken which, he says, was quite the opposite – no reverbs, etc. "And it just didn't sound right. So we kind of came to a balance between the two."

The original recordings, to some degree, limited how much remixing could be done. "Nearly every song has a stereo guitar track," McDonald, due to the limited space of 8-track tape, having combined both George's and Eric's electric guitars with the acoustics – and, often, with reverb – onto two tracks, making it impossible to create a new mix with those items separated. "We tried various kinds of software to get rid of the reverb, but it was really better just left alone."

Some songs, like "If Not For You," he says, actually sounded quite good "dry," without reverb. But with a clamorous track like "What Is Life" following it, with printed reverbs, he notes, "It just didn't work," so it was given a more full mix. Similarly, "We tried doing 'Apple Scruffs' without the delay effect, and it just sounded like a demo." The same for "Let It Down" and "Hear Me Lord" – "Without the slap delay on the drums, it just didn't sound right."

The one thing that benefited from an absence of reverb was George's vocals. "He has a voice that lends itself to that. And with a lot of the outtakes and extras, we've just kept his voice really, really dry, because that's what George liked. And it works."

Hicks started his remixing work in Los Angeles, but then also used Abbey Road's resources, to accurately replicate ADT and other effects, as well as working at FPSHOT, George's original studio at Friar Park. Some effects, though, such as the wobbly piano on "Isn't It a Pity (Version 2)," had the effect tracked to tape originally, so they were left as is.

As for George's demos, recorded on the first two days of work, the decision was made to simply present them intact, in order, the first day's work with Ringo and Klaus on one disc, and the second day's work on a second disc.

For the Dolby Atmos mix, something at which Hicks excels, he says, "It's a really, really immersive mix. Probably the most immersive mix I've done." For the stereo guitar tracks, mentioned above, he placed those to the sides and the back, to provide a deeply immersive mix. "They're nicely balanced to begin with. So you constantly feel 'in it.'" He took advantage of the height of the Atmos volume, to place Harrison's vocal more within the space, giving a more intimate experience. And the Trident overdubs, with additional tracks of material, gave him yet more layers to play with, for songs such as "My Sweet Lord," with items like the multiple background vocals, strings and autoharp, and "Let It Down" and others.

For the outtakes disc, he notes, "Some songs, like 'Wah-Wah,' there were only a few takes. And then, others, they tried a few different versions," noting a favorite version of "Isn't It a Pity" as well as one of "I'd Have You Anytime." "It's really interesting – a brilliant outtake. It's got this 'verby piano, and it's higher tempo."

"I think fans are going to be pleased. The album is one of the great treasures of George's catalog. And now it sounds simply amazing."

Thanks to: John Leckie, Ken Scott, Klaus Voormann, Peter Frampton, Bobby Whitlock, Joey Molland, John Barham, Tim Plumley, Jason Kruppa, and Chip Madinger.