The Making of All Things Must Pass Page 3

Additional players or guests would show up on occasion, typically arriving and asking, "Where can I plug in," sending Leckie scrambling for additional headphones. "I remember Donovan actually came once, dressed in a white suit – I was in awe," he remembers. Pink Floyd's Rick Wright came one day, as well. "He suddenly appeared. I knew him, and he said to me, 'Someone said they wanted a piano player.' We already had four piano players, we didn't need any more! So he left."

Spector would encourage anyone who could play – or even appeared to – to join in. "I was once tinkling around on the Wurlitzer, just testing it, and he came up to me and said, 'Hey, John – do you play piano? Want to play on this track?' I told him, 'No, I've gotta look after the tape.'"

Tracking

Sessions began each day around 2 or 3 in the afternoon, breaking at around 11 or 12 at night, while Spector would, typically, go back to his hotel or have dinner, before returning at 12 or 1 a.m. to continue until 8 or 9 in the morning, Leckie says. "Whenever he came to England to work, he always stayed on L.A. time – he was always 8 hours behind."

When it came time to start a new song, George would usually pick up his acoustic guitar, with the guys gathered around, and play them the song. "Everyone would take notes in their minds or write the chords down," says Whitlock. "But mostly, we just listened and played along. Then it fell together."

It was up to the musicians to develop parts and work out the arrangement. "George didn't tell anybody what to play," Whitlock notes. "You're dealing with pros. When you have that caliber of players, you just sing a song, and they start playing. You don't have people that can play like that, and then go tell them what you want. You get me because I play what I do, or I wouldn't be in there." Voormann noted the same. "Nobody ever told me what I was supposed to play. It was more down to each individual. I just listen to the song, and then play what I think is right. We would all do that – try something out, and if you feel, 'That's not the right lick. What fits?'"

Harrison might suggest, "'Don't play the electric piano, go and play the organ,'" the bassist explains. "He might also play the song on guitar, but then change a portion because he feels, 'Well, with a band, that doesn't sound right. Let's rather do a straight 4-beat or something,' And then we'd all adjust what we play to his new idea."

Spector really took no role in the arrangements. "He left it to George and left it to the musicians. I didn't ever see him come and tell anybody what they should play. He left it to George. He was very delicate, not upstaging himself. He left it to George's musical ability." Any comments he had went to George in his headphones alone.

He did, however, love being the center of attention, at least in the control room. "They'd come in for playback, and Phil would start talking about Lenny Bruce or something," Leckie recalls. "He would be holding court and everyone would be laughing at his jokes. He would talk and talk, until George would have to say, 'Hey, shall we get on with the record?' or 'Should we go and do another take?'"

As far as playback goes, Whitlock seemed to take the most interest, when the band would come to the control room. "He was quite involved," says Leckie. "He was always talking to George, and had a lot to say."

Basic tracking for each song was very much in the Spector "wall of sound" mode – the full band tracking together, including horns and a scratch vocal from George (which, if he felt it was right, was occasionally kept). Any overdubs, at least for major parts, took place right after a master take was selected, with Whitlock and Clapton adding background vocals (or together with George, as the "George O'Hara-Smith Singers," as the credit reads), or Harrison playing a guitar solo. "They would do the track and say, 'Right – that's the take. I'll do the slide' or 'I'll do the tambourine,' all done in the same session," Leckie explains.

A common overdub was Ringo, often joined by Mal or Mike Gibbins, doing tambourine overdubs. "I can remember seeing Ringo taking two tambourines in each hand, and he would stand there and bang them on his hips. And with two guys standing there, it sounded like four tambourines, instead of one tambourine. That's why it's so huge," something Leckie took with him once he became a producer himself. "Even today, every time I'm producing a record, and I use a tambourine, I always make sure we've got two, and played just as Ringo did, against the hips."

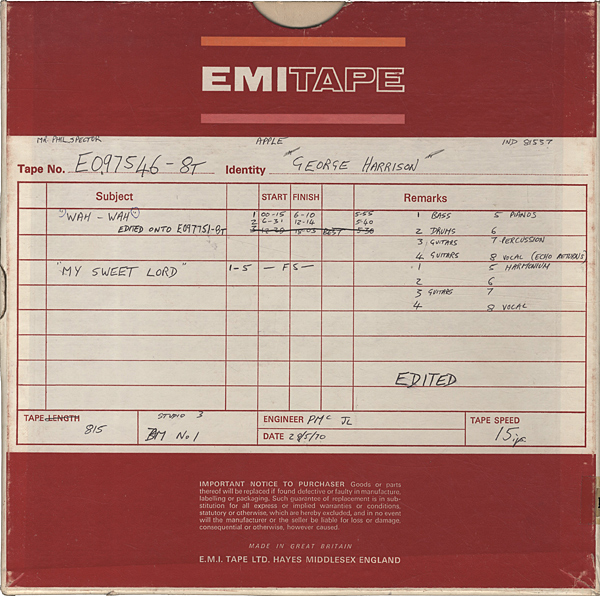

Thursday 5/28/70

The first song to be recorded was the raucous, powerful "Wah-Wah" (whose very first take can be heard as a bonus track on the 50th anniversary reissue) The recording featured the full lineup in action, Klaus, Ringo, two electric guitars, pianos, acoustics and live horns. "It was incredibly chaotic," says Leckie. Recalls Molland, "It was an enormous amount of sound in your headphones. It was super powerful. It was great."

The wall of sound was in full swing, and with only 8 tracks available, Spector had McDonald record, as was often the case on the sessions, all guitars mixed to a pair of tracks – both electrics and the acoustics – on rare occasion with reverb. The drums – even with two drummers – were mixed onto a single track, with reverb or other effects added later in the mix.

When the band started working on the song, there was one person missing. "I had a little 2.2 Porsche, and I decided to drive myself there, and I got caught up in the roundabout in front of Buckingham Palace," Whitlock recalls. "The traffic was just awful." By the time he arrived, he found the other keyboards (Preston on piano, Gary Brooker on organ) already spoken for, hopped on the Wurlitzer. "Everybody else was playing on the downbeat, so I played on the upbeat – that was the only thing left," he says of his unique part, heard on the right, complementing Clapton's wah-wah part. It is George, of course, heard on the left, playing the song's signature riff, on his Stratocaster. Only three takes were required, Take 3 being the master, onto which Ringo added tambourines as an overdub.

"Wah-Wah" completed, the group next recorded a very different kind of song, and one which would become its first single, "My Sweet Lord." George had written the song while on tour with Delaney & Bonnie, and had given that song, along with "All Things Must Pass," to Billy Preston to record on his Encouraging Words Apple LP, which George was producing, in January. Of 16 takes, just two were complete takes, the first 5 of which featured only acoustic guitar, harmonium and piano, before the full band was introduced, Take 16 becoming the master. Harrison can be heard on his Harptone acoustic on the right in the mix, with Badfinger strumming in perfect unison on the left. Ringo is drumming, with Billy Preston on piano. Tambourines were recorded that day, likely by Ringo as an overdub, or else live, perhaps by Mike Gibbins.

John Barham found himself drafted to play the harmonium part, live in Room 43. "He was quite nervous," Leckie recalls, "because the room was full of people. And he would come in and say to me, "I don't know what I'm doing here. Why am I playing with all these people?'" he laughs. The part was, of course, perfect, recorded together on one track with Preston's piano. Barham can also be heard playing autoharp accents throughout the song.

Though Molland has a recollection of Clapton busily trying to work out the song's signature slide part during run-throughs, it is George himself who played two passes of the slide heard on the finished recording, tracked as overdubs later in the year with Ken Scott at Trident Studios.

Harrison had learned to play slide at the end of the previous year from Delaney Bramlett, while on tour, and quickly became a favorite part of his guitar-playing arsenal – both for himself and his fans. The slide part was double-tracked, as was always Harrison's method. "He was very methodical about his solos," Voormann reveals. "George was very, very slow, and he'd do a pass, over and over, saying, 'No, no, now do it again," until he worked out a solo. It took ages. And Spector didn't have the patience for it." The results speak for themselves, his slide during this early 70s period uniquely both hot and melodic, every pass.

The song took many hours to complete, finishing at about 3 or 4 a.m. – at which time, Leckie recalls, "they said, 'Hey, let's do another song,'" and went straight into what would eventually become the album's opening track, 'I'd Have You Anytime" (or, at that time, "I'll Have You Anytime"), co-written by George and Bob Dylan in late 1968 at Dylan's home in Woodstock. Six takes were recorded that day, though the song would be returned to and completed the following day.

The next day, Friday May 29, the group did more recording on the song, finding the master in the 7th take. Badfinger once again joined George on acoustic guitars, and Clapton plays the bluesy opening and accent guitars. Whitlock adding a harmonium – and there are even vibes, played either by Barham or White.

With the song completed, the group moved on to nine takes of "Art Of Dying," featuring a pair of pianos (Preston and Gary Brooker, likely), the final take marked "M?" as the perhaps-master (its first take from this day appears now as a bonus track). The song, though, would be returned to twice more, finally a month later, on July 1, which would generate the true master. The same would be for "Run of the Mill," for which just two simple takes were recorded, with just George on his acoustic and his vocal, also recorded for real on July 1.

Five takes of another song were begun that day, as well, whose master would be found after a three-day weekend, on Tuesday June 2, recording the last song of what would be the album's first side – "Isn't It a Pity." The bed of the recording is formed by a combination of Badfinger's rhythm acoustics and piano parts played by both Billy Preston and also Gary Wright, his first session on a George Harrison album, and someone who would remain a close friend and collaborator of George's for the rest of his life.

"George asked me, 'Oh, Klaus, who can I ask for keyboard for this?' I had just played on Gary's first solo album," following Wright's stint in Spooky Tooth, Extraction, "and told George, and that he's a really mellow guy, would fit really well. And they became great friends." Wright plays throughout the album, sometimes turning in piano with a slight country bent to it.

Drums are handled by Ringo, with Klaus on bass, and Whitlock on the Hammond L-100, also adding a harmonium as an overdub. Curiously, on the May 29 recording, there is both an electric harpsichord (again, likely played by Barham) and a Moog synthesizer. The latter was played, according to Jason Kruppa (author of All Things Must Pass Away, co-written with Kenneth Womack, about Harrison's and Clapton's collaborations) by another former Abbey Road veteran, Chris Thomas, by then George Martin's assistant at AIR Studios. Thomas's part was wiped, though, from the reel and replaced with a guitar and vocal. Ringo added his double tambourines, as well. "There were a lot of takes – and it's quite a long song, too," Leckie notes. "And they take breaks in between and jam" (see jams, below). 19 passes found the master.

The Side 4 opener, "I Dig Love," was also tackled that day. A few passes were made with acoustic guitars, plus Eric on electric, Klaus on bass, and Whitlock on Hammond and Wright on grand piano, but the next passes added Preston on the Wurlitzer, making the song, in its mix, essentially a wonderful keyboard track. The song features Ringo, receiving fast tape slap echo in the mix of the master, Take 20.

A second take on "Isn't It a Pity," which would appear as a "Version 2" on the fourth side of the album, was recorded the next day, this time with Clapton's guitar put through a Leslie 122 speaker, a now-common effect at Abbey Road, courtesy of a homemade interface box which allowed plugging in a guitar or a microphone, instead of a Hammond organ. Take 30 was the master.

Billy Preston was now on piano, and as was the case with Whitlock's Hammond, was given a special "wobble" effect, effected by tape operator Leckie, operating a second, 1/4-inch tape machine. Connected to the machine was a Varispeed control—a Levell rheostat with a dial, which would vary the speed of the tape machine's capstan, like a pitch control knob, something invented by studio engineer Ken Townsend during the Beatles period to allow "automatic double-tracking" (or "ADT") of lead vocals, by creating a slight delay in the signal during mixing.

"You would move the Varispeed knob between two limits, marked on the dial with a Chinagraph marker, and you could wobble it," Leckie explains. "And if you capture it on the null point, you get the traditional "phasing" or "flanging" sound. And if you move it quickly, with the momentum of the tape movement, it would swing faster and slower. It's something you can't do digitally – you can't do it with a computer – I've tried. It can only be done analog. It's a sophisticated effect, and it's the only way you can get it." The effect was also applied to Whitlock's Hammond.

Thursday June 4 saw the first pass at a new Bob Dylan composition, "If Not For You." The song would be attempted the next day, Friday June 5, with the addition of two new players.

Pete Drake was the most respected pedal steel guitar player in Nashville – and who would shortly produce Ringo's second solo album, Beaucoups of Blues. Drake recalled in an interview in Guitar Player, his assistant buzzing him, noting a phone call, "George Harrison wants you." Pete answered, "Well, where's he from?" "London." "Well, what company's he with?" "The Beatles." Noted Drake, "His name, you know, just didn't ring any bells. Well, I'm just a hillbilly, you know." But Drake was happy to accept the invitation to play, and arrived at Abbey Road, with his pedal steel in tow, a few days later, on Tuesday June 9.

"They were in awe of him," Leckie recalls. "As far as George was concerned, he was the god of pedal steel guitar." Drake's steel was unpacked and set up, and the master spent some time demonstrating his licks on the instrument, as well as another device he had brought along – a "talk box" (or referred to as "Pete Drake's talking guitar"), popularized not long after by Joe Walsh and. . . Peter Frampton.

And the latter is not by coincidence. Earlier in May, Frampton was leaving Humble Pie, and was visiting with Terry Doran, a mutual friend of his and George's, at the Marquee Club on Wardour Street. "He asked me, 'You want to come and meet Geoffrey?'" an apparent code name for Harrison. The two walked down Wardour Street to Trident Studios on St. Anne's Court, where George was working on the Doris Troy album. "We came in, and there was George at the console, and he said, 'Hi, Pete.' I thought perhaps Pete Townshend must have walked in behind me!"