Recording and Remixing Revolver

Beatles fans gain new insights into the creation and lasting legacy of this goundbreaking album with a series of new special editions.

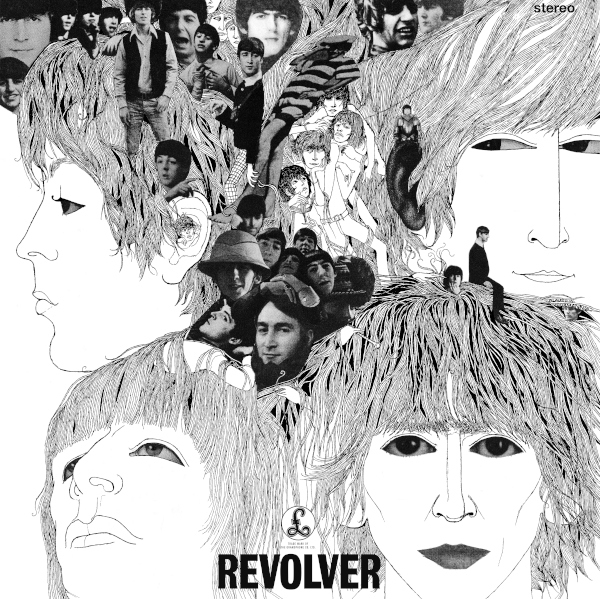

For many Beatles fans, Revolver is their favorite album. A balance of great songwriting and first dips into experimentation and change even place the 1966 LP above Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and Abbey Road for some. And while George Harrison himself considered Revolver and its predecessor, 1965’s Rubber Soul, to be brother and sister albums, the album was a clear step forward into new kinds of music, fresh sounds, and pioneering recording techniques.Following in line with Special Edition packages of Sgt. Pepper, Abbey Road, The Beatles (a.k.a. The White Album), and Let It Be, Apple Corps, Ltd/Capitol Records/UMe today released a series of new special editions of Revolver featuring the original mono mix and a new stereo remix by Giles Martin (son of original producer Sir George Martin) and engineer Sam Okell. Martin has also prepared a Dolby Atmos mix of the album, now available via streaming.

Topping the physical releases are the Special Edition Super Deluxe 5CD ($139) and 4LP+EP ($200) sets, both of which include two (CD or LP) Sessions discs full of studio outtakes, an EP highlighting the single “Paperback Writer”/”Rain,” which was recorded during the sessions, and a hardcover book with historical notes and session details by renowned Beatles historian Kevin Howlett, who, with longtime colleague Mike Heatley, researched the story behind each of the 16 songs that make up Revolver and its single.

Even though it is a far simpler recording than the albums that followed, Okell notes, “It’s kind of a sweet spot, between the early, more basic recording-the-band-live recordings and the Pepper world of overdubbing and layering things up, which came after.” The group’s excitement — heard not only in the outtakes but in the released recordings, brought even more to life via the new remix — is unmistakable. “There’s such energy that comes out of all of the tapes,” Martin says. “They were an extraordinary band. And when they got together, they did extraordinary things.”

Rubber Soul was completed on November 11, 1965, and rush-released on December 3rd, accompanied by — as was the practice in the U.K. — its smash non-album single, “Day Tripper” b/w “We Can Work It Out.” As Howlett explains in the “Road to Revolver” chapter of his book, time had been set aside for production of The Beatles next theatrical motion picture for United Artists in the first few months of 1966, but all of that changed when it was deemed that the script was not satisfactory, and the project was put on hold. With three months of unexpected free time on their hands, “they were able to step off the merry-go-round.”

Even at such young ages — George was 23, John was 25 — they had never had a chance to just. . . breathe and grow, as young men. Each began exploring things that interested them, much of which would influence them musically as they began to write and record when they entered the studio again in early April of 1966. “Paul was getting into meeting [fellow musician] Peter Asher’s friends, like [avant-garde] artist John Dunbar and Barry Miles, going to [experimental composer] Luciano Berio concerts. And meeting William Burroughs, who used cut-up techniques when writing his poetry,” Howlett explains. Paul made note of the idea, which would find its place on Revolver. “All of these things are just blowing his mind. And George has developed a passion for Indian music. And, of course, when one Beatle has a passion, they all share it.”

Their songwriting began to advance, as well as their musicianship, reflective, too, of the changes in rock music happening during this time. “They were not living in a bubble,” notes Beatles instrument historian, Andy Babiuk, author of Beatles Gear. “They were out, partying, going to clubs. They were the kings of London — they were the frickin’ Beatles.”

“I sat with Paul and listened to the new mixes together, as we always do,” Martin explains. “And I think the biggest change in their writing was probably rhythmically. Their rhythm texture — they change gears. ‘She Said She Said’ and ‘Rain’ are different — there’s more swagger to them. And then, suddenly, there’s ‘Paperback Writer,’ which is much more driving. You look at ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’ and George’s ‘Taxman.’ The rhythms are more sophisticated. There’s not a formulaic pattern. They truly left Merseybeat behind.”

During their extended break, Paul would make the drive down to Weybridge to have writing sessions with John at his home. “He might have an idea, on his way down, such as ‘Dear Sir or Madam’” — the start of “Paperback Writer” — “and they’d work on it together,” says Howlett. It was a practice that would continue even during recording, on days off, either together or alone, as evidenced by John’s lyrics to “I’m Only Sleeping,” written on the back of a late notice he had received for a bill (and reproduced in the book) — dated just a day or two before the group recorded the song.

Their abilities as musicians also grew and changed during this period. “Listen to Paul’s guitar playing on ‘And Your Bird Can Sing,’” points out Beatles historian Brian Kehew, who, with Kevin Ryan, authored the heavily-researched 500-page Recording The Beatles. “He’s playing together with George, and playing some pretty quick licks. They had grown and exceeded what they’d been capable of before.” Notes engineer Bill Smith, a longtime close friend of Geoff Emerick (who recorded the album), “The earlier records didn’t really afford them the time to experiment and come up with more creative ideas, where they could expand their playing. This one did.”

New Fab Gear

The Beatles’ musical and recording toolboxes were expanded around this time, giving them more ways to create new sounds. Especially evident is the presence of a new electric guitar, the Epiphone Casino, with Paul making particularly strident use of it on a number of tracks.

While John and George acquired theirs that spring, Paul actually got his at the end of 1964. As Babiuk explains, “The pubs would close early at that time, and everybody was wound up and still wanting to keep going. So they would go to John Mayall’s house, to listen to old blues records because he had the best collection.” Mayall explained to Babiuk that Paul was excited to learn how musicians got the rich tone heard on those records. “He said he told Paul, ‘Well, you gotta get a hollow body electric guitar, like a Gibson or something.’”

So McCartney went to a guitar shop in London and bought an Epiphone Texan acoustic guitar and a right-handed Casino, flipping the string order to make it left-handed. “There are actually photos of George and Paul in December 1964 when they were doing a Christmas show, looking at Paul’s new guitar and trying to figure out how to flip the guitar’s bridge the other way. Several weeks later Paul used it for the first time in the studio, playing the lead on ‘Ticket to Ride.’”

Around that time George had acquired a Gibson SG for similar reasons. “They played in the States the year before, and he had seen a lot of guys here using Gibsons, and getting a fatter tone,” Babiuk notes. “So he went out and got a Gibson hollow body ES. “He had said in an interview later, he realized his guitar tone on early Beatles records was kind of thin. He knew a Humbucker guitar pickup would sound thicker, and hence, he acquired the SG, which you hear in this time period.”

While Paul did use his Hofner bass on Revolver, he also made prominent use of the Rickenbacker 4001S, heard most notably on “Paperback Writer,” which he had actually been introduced to two years earlier. According to Babiuk, Rickenbacker’s U.K. distributor, Rosetti, had written to F.C. Hall, the company’s U.S. owner, letting him know of a big band in England — The Beatles, of course — that would shortly be coming to the States, and suggesting he get in touch with their manager, Brian Epstein, about meeting them.

Hall did so and came to New York in February 1964 — bringing with him a prototype 12-string guitar, a new full-size 6-string model, and a left-handed bass — with the intent of presenting them to the band. “The problem was,” says Babiuk, “they weren’t making any money yet, so they thought it was some kind of sales pitch — meaning they would have to buy the instruments. They didn’t understand he was giving the instruments to them!” Hall said the bass was indeed presented to Paul, who responded, “I’m really happy with the bass that I have. It's nice, but thanks.” John similarly passed on the 6-string.

George was sick in bed with a cold at the hotel, so Hall brought the 12-string to him there. He began picking away on the instrument, while on the phone with a local deejay — who offered to buy whatever guitar that was for him if he would play a tune on the air. “So in George’s mind, he got it for free — because the deejay bought it for him. He didn’t. F.C. Hall gave it to him.”

The following year, in August 1965, when The Beatles were playing in Los Angeles, Hall and his son went to visit the band in the house they were renting, once again bringing along the left-handed 4001S to give to Paul. “Paul loved it. And that became the famous Rick.”

Guitar manufacturers weren’t the only ones giving their newest products to popular bands, hoping that they would make use of them and maybe even talk about them. As one of Vox’s principals and amp designer, Dick Denney, told Babiuk, “When the company made a brand new amp, the first people who would get it, at that point, were The Beatles — period.”

Vox’s U.S. distributor was working on an amp with new solid-state circuitry that would eventually find its way into the powerful “Super Beetle” amplifier The Beatles would use on their U.S. tour in 1966. The circuit design appeared first in a new guitar amp with a solid-state preamp that fed the signal to Vox’s dependable tube output. “And that’s the model 7120, which you see them using predominantly in the studio on Revolver,” Babiuk explains. The amp had a 120-watt output and four 12-inch speakers. A similar model, the 4120, with a pair of 15-inch speakers, was built to give to Paul to use as a bass amp, though it appears he preferred using the 7120 for that purpose.

The Beatles can also be seen with Fender Dual Showman guitar amps, which offered a truly clean sound, though it is unknown if/when it was used on the recordings.

A key element to the sound of Revolver also emerged during the sessions — guitar distortion. The Beatles had played with distortion over the previous years, the first time being in 1963, when John brought in a Maestro Fuzz Tone box. “But George Martin told him, at the time,” says Babiuk, “’John, we’re trying to get the guitars to sound clean. And you’re just causing it to sound very distorted. We won’t have that.’” A box was used by Paul to provide the over-fuzzed bass on George’s 1965 Rubber Soul track, “Think for Yourself.”

But it wasn’t until The Rolling Stones released “Satisfaction” in August 1965 — featuring Keith Richards playing the song’s signature riff through a Maestro fuzz box — that everyone just had to have one. So the Fabs began using a WEM Rush Pep distortion box on Revolver, along with other boxes, such as the Tone Bender or Maestro, to produce distortion. The Rush Pep box was made by Pepe Rush of Watkins Electric Music (WEM). “WEM didn’t make many of the Rush Pep boxes,” informs Kehew. “So they’re quite rare and expensive — because The Beatles used them.”

Even so, it’s not clear what box was used to achieve the signature distortion heard on so many Revolver tracks, such as “She Said She Said,” “And Your Bird Can Sing,” and others — or if it was even a box. Amp manufacturers, such as Vox, did begin including distortion/fuzz circuits in their amps, as well. “They either cranked up their amps, taking advantage of the distortion a tube amp would make,” says Kehew, “or they used one of the pedals.” Babiuk agrees. “There’s no way to tell what they used, really.”

On the drum side, Ringo actually had two full drum kits in the studio during the sessions, one with a 22-inch kick drum, which he had just come off the road with in 1965, and one with a smaller, 20-inch kick drum, notes Babiuk, who has examined — at Starr’s behest — all of his drum instruments. “He had two 22-inch and two 20-inch kicks, at the time [but] it’s the 22-inch that is heard most on this album.”

New Man Behind the Glass

|

Engineer Geoff Emerick in his early years at EMI’s studio at Abbey Road. Photo courtesy of Abbey Road Studios. |

Geoff Emerick had been listening to records since he was 6 years old, hearing 10-inch 78 rpm classical records — such as “Madame Butterfly,” “Rhapsody in Blue,” and the Brandenburg Concertos” — on his toy Gramophone in his grandmother’s cellar. “I just fell in love with them,” he told me when I interviewed him in 2006. “I just knew, I’d like to be involved with putting music on records.”

Ten years later, at age 16, he was sending out application letters to all the record companies in town, receiving rejection letter after rejection letter. But help from a school careers official got him an interview at EMI’s studio at Abbey Road — even after being rejected on his first pass.

Emerick began working at EMI Recording Studios (renamed Abbey Road in 1976) in September 1962, around the time of The Beatles’ first recording session for “Love Me Do.” As with all new recruits, he began as a “2nd engineer,” mainly functioning as the tape machine operator (in absence of any kind of remote control system, which came decades later). “Being the new guy, I was put on classical sessions. And I loved the emotion that I’d hear, live, being recorded straight to stereo.” Pop recording sessions would also typically be recorded to “twin-track” (as was the case of The Beatles first two LPs) or just mono.

He assisted on only a small number of pop sessions, after being assigned to other tasks. He did indeed get to work alongside Norman Smith on numerous occasions — including several Beatles sessions, starting with the piano overdub on “Misery” from their first album, “She Loves You” in July 1963, and “A Hard Day’s Night” the year after. “There was always a huge buzz, when they were coming in,” Emerick recalled.

“Norman Smith taught me a lot. One thing he said quite often was, ‘It happens down in the studio, not really in the control room,’ which was really the case at that time. Because what did we have? We had eight mic inputs, very limited EQ, a tape machine, and an echo chamber. That was it.” He also learned another valuable lesson. “Norman always said, you could lift up one fader/mic in the studio, if they were routining or rehearsing something. And no matter who it was, you could hear whether you had a hit on your hands or not.”

After a time, Emerick was assigned — as was the practice — to cutting the playback lacquers artists would listen to at home before mastering lacquers were cut and sent to the record plant. Though he never cut discs for any Beatles records, he did learn from the man who did, mastering engineer Malcolm Davies. “I learned all my mastering skills from Malcolm — he was brilliant,” Emerick noted.

He did, however, work on recordings from the States that had to be cut for release in England. “I was in awe of the sound of the American records, compared to our records. They were louder, and the bass content was a lot heavier. And they were brighter.” He would take these experiences with him, when he was promoted to balance engineer in early 1966 at the age of 20 — a promotion that took him by surprise.

“He hadn’t really done much music balancing, at the time he was asked to become The Beatles’ engineer,” Howlett observes. “But he did have a current No. 1, when they were making Revolver” — Manfred Mann’s ‘Pretty Flamingo,’ which he’d balanced just a month or so before. So he was clearly a talented engineer.”