Connections for a High-Def World

Ah, the golden age of television. The only thing I loved more than Lucy was the solitary input on the back of my TV. It was a simpler time. Now we must choose between 300 channels and only slightly fewer inputs. Add HDTV to the mix, with all of its inherent confusion, and it's a recipe for connection disaster.

Component Inputs

Studies consistently show that many HDTV owners aren't watching HD content, either because they aren't getting it from their provider or they don't have their TVs connected correctly. A quick call to your cable/satellite provider can take care of the former, and a quick read of this HD-connection primer can help with the latter. Some TVs and projectors may have HD-capable inputs not listed here; however, for simplicity's sake, we've chosen to focus on the three you're most likely to find on a consumer HDTV.

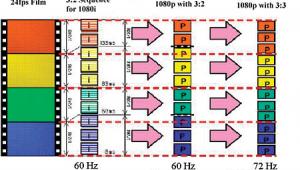

All three of these connections can support HD resolutions up to 1080p, but it's up to your TV's manufacturer to decide which resolutions to support through each connection. For bandwidth and copy-protection reasons, many choose not to accept 1080p via component video; some don't even accept it through HDMI. An owner's manual will usually list which resolutions each connection supports, so you should do your homework before you buy.

Component Cable

Component Video

Digital connections may be the buzz, but component video is still the standard for sending HD signals from a source to a TV or receiver—at least for the time being. Component video isn't just for HD, either. It's often the highest-quality output on SD sources like DVD players, as it allows for a much cleaner, more colorful picture than lower-quality analog connections like S-video and composite video.

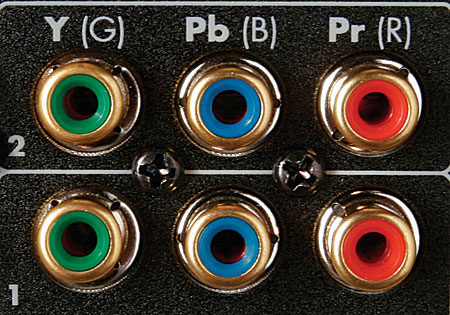

DVI Cable

Component video splits the video signal into three parts, labeled Y, Pb (or Cb), and Pr (or Cr). Both the connections and the cable are color coded: green for Y, blue for Pb, and red for Pr. The Y element carries the signal's luminance information—which is primarily green, plus enough red and blue to make the image look black and white—and the horizontal and vertical sync pulses that tell the TV when a new frame begins. The Pb element carries the remaining blue, and the Pr element carries the remaining red. RCA is usually the connector of choice for component video, although some professional and high-end equipment may use the twist-and-lock BNC connector for a more secure connection. Prepackaged three-in-one component video cables are easy to find, or, in a pinch, you can simply use individual 75-ohm video cables for each element, as long as they're each the same length and type.

I should stress that not every component video input has the bandwidth to pass a high-definition signal. If one of your HDTV's component video inputs is labeled "480i/480p," that means you should only use it for standard-def sources. With most new HDTVs, it's safe to assume that, unless the component input is labeled otherwise, it is HD capable. If you own an off-the-shelf upconverting DVD player, it is unlikely that you'll be able to view store-bought DVDs at a 1080i or 720p resolution through component video; you must use a digital connection.

DVI Input

Component video is a stable connection that can travel over long distances with minimal degradation, which is why it remains a popular choice in the custom-installation world. In spite of its current popularity and ubiquitous nature, component video will someday fade from the HD landscape, primarily because it lacks the copy protection to protect high-quality digital sources.

DVI

Like component video, the Digital Visual Interface (DVI) connection splits the video signal into three elements to improve image quality. Unlike component video, the digital signal remains in digital form, sent in a format called Transition Minimized Differential Signaling, which divides the signal into its green, red, and blue/sync elements. This connection has its origins in the computer realm and has the bulk and appearance to show for it.

DVI-to-HDMI Adapter (front)

DVI allows you to transmit a fully digital, uncompressed HD signal from source to TV, bypassing the digital-to-analog conversion processes that can potentially degrade signal quality in an analog connection. Because the DVI signal is not compressed, it's much too large to be recorded, which means DVI—and consequently HDMI—is not an option for sending HDTV from a set-top box to some form of digital recording device. (See sidebar.)

To further protect content, DVI employs a form of copy protection called HDCP, or High-bandwidth Digital Content Protection, which prevents DVI devices from communicating properly unless both have HDCP in place. In the home theater realm, many first-generation DVI-equipped displays did not use HDCP and therefore will not display an image coming from a new DVI-equipped DVD player or set-top box. If you're having no luck getting a picture when connecting two devices via DVI, chances are that one of them lacks HDCP—and I'm afraid you're completely out of luck.

DVI-to-HDMI Adapter (back)

Of the three connection types, DVI is the least reliable over a longer video run. The official DVI spec only requires that the equipment maintain the signal up to 16 feet, although you can purchase DVI extension and repeater devices to allow for a longer run. As HDMI becomes increasingly popular, DVI connections are disappearing from new video products.

HDMI

The High-Definition Multimedia Interface (HDMI) represents the evolution of DVI. In terms of how it handles a video signal, HDMI is identical to DVI, passing a fully digital, uncompressed signal between source and display. HDMI ups the ante by allowing for the passage of uncompressed multichannel audio and control information. These uncompressed signals are too large to be recorded.

HDMI Input

HDMI has a smaller, more user-friendly form factor than DVI, but the two are usually compatible through the use of a simple adapter, as long as both employ HDCP copy protection. HDMI is more reliable than DVI over a longer video run. If your run is longer than about 20 feet, it may be worth the extra money to invest in a high-quality HDMI cable or an HDMI amplifier or repeater from a company like Gefen or Acoustic Research.

For all of its potential benefits, HDMI can be frustrating to use in its current form. Communication failures abound. Sometimes, you must cue up devices in a particular order to ensure that you get a picture. Other times, a source and a display will communicate well—until you add an A/V receiver to the mix. We've already encountered several instances in which an HDTV and a high-definition DVD player had difficulty communicating over HDMI. Silicon Image, the company that invented HDMI, has attempted to address this through their Simplay HD certification process, which tests a product's HDCP functionality and its interoperability with other HDMI devices. Products that sport the Simplay HD logo have been verified to work together. This is a step in the right direction, but only a few manufacturers' products are currently certified. (For a list, go to www.simplayhd.com.)

HDMI Cable

If and when its bugs are worked out, HDMI could usher in a new golden age of TV, filled with beautiful HD programming and TVs with just a single input. Those would be the days.

Want to Archive Your HDTV Recordings? Ask for FireWire

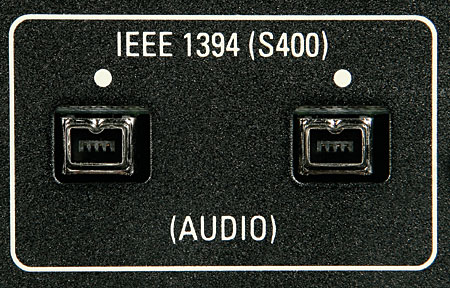

The good news is that there are plenty of HD DVRs and Media Center PCs that allow you to record your favorite TV shows in HD. The bad news is that, until Blu-ray and HD DVD recorders hit the market (hopefully this year), saving those recordings to a disc presents a challenge. FireWire, or IEEE 1394, remains our best hope for transferring and archiving HD video signals. If your TV or cable/satellite set-top box has active FireWire ports, you can transfer HD recordings—at least of unencrypted channels like ABC, CBS, and NBC—to a recording device, such as a D-VHS recorder or a computer with a Blu-ray or HD DVD burner. In 2004, the FCC mandated that cable companies must give you a FireWire-equipped cable box if you ask for one. So speak up.

FireWire Inputs

FireWire Four-Pin Cable (left) and Six-Pin Cable (right)

Audio in HD

Optical and coaxial digital audio connections have long been the standard method of transferring multichannel digital audio signals from an HDTV or HD set-top box to an A/V receiver, but HDMI is coming on strong. Electronics manufacturers are paying more attention to a receiver or pre/pro's ability to accept both video and audio via HDMI so that you only have to run one connection from a high-definition source, such as a cable box. Current HDMI specs allow you to pass PCM, Dolby Digital 5.1, DTS, DVD-Audio, and SACD; Dolby is the most common format for HDTV broadcasts.

With the arrival of high-definition DVD and the new uncompressed Dolby True HD and DTS-HD Master Audio formats, everything gets a bit more complicated (naturally). With the first crop of high-definition DVD players, you can send compressed Dolby Digital and DTS audio the old-fashioned way, through the optical or coaxial outputs. Or you can let the player decode the Dolby TrueHD and DTS-HD Master Audio internally as uncompressed, multichannel PCM and send it over HDMI to your receiver. The HDMI 1.3 spec, which is just beginning to appear on products, lets you pass the Dolby TrueHD or DTS-HD bit stream directly through HDMI to the receiver—if manufacturers and content providers enable it. Confusing? You bet.