HDR: The Other OLED

What makes a good TV picture? Sharp detail? That’s a factor, sure. Vibrant color? Of course. What about brightness? Definitely, you don’t want a dim picture. How about black level? That’s vital. After all, you don’t want grayish blacks; that wouldn’t be lifelike.

The biggest key, however, to a really spectacular image is the combination of brightness and black level. Contrast ratio—the difference between the brightest image a TV can produce and the darkest—is the most important aspect of a TV’s overall picture quality. Yes, you need good color and detail, too (and low noise, and some other factors), but a truly impressive contrast ratio is going to win out. We’ve seen this time and time again here at Sound & Vision (and before, at Home Theater).

New TV technologies like OLED and LCDs with a local-dimming LED backlight (and “old” technologies like plasma, may it R.I.P.) can create some extraordinary contrast ratios, but they’re still nowhere near what the human eye is able to see.

That’s where HDR, or High Dynamic Range, comes in. And the potential is awesome.

All About the Contrast

Several years ago, I conducted an epic (if I do say so myself) TV faceoff, where a group of panelists (professional reviewers and enthusiasts alike) compared several LCDs, plasmas, and even the last of the DLP rear-projection TVs. All were calibrated, and all displayed the same 1080i HD signals. The TV that won, hands down, wasn’t just a plasma but a plasma with 720p resolution—roughly half the pixels of the other TVs. Why? The winner had a significantly higher contrast ratio. That TV was a vaunted Pioneer Kuro, a member of one of the greatest TV lines of all time.

More recently, Value Electronics in Scarsdale, NY, conducted their own annual TV face-off, and while their methods were a bit different, the winner their customers and members of the electronics press chose was the new LG 55EC9300 OLED, almost entirely because of its incredible contrast ratio. And that was against a bevy of local-dimming LED LCDs, and even the last of the great plasmas, the Samsung F8500.

I, and nearly every other TV reviewer, can confidently say that contrast ratio is the most important aspect of picture quality. It’s easy to see why. A high-contrast image looks more realistic and offers more apparent depth, while a low-contrast image appears washed out and artificial.

Dolby and several other companies want to really push that envelope of brightness and black level, expanding the contrast ratio into something they call High Dynamic Range.

Increasing a TV’s contrast has been one of the main picture-quality goals for all manufacturers, regardless of their chosen technology. Achieving deeper and deeper black levels—one half of the contrast ratio equation—has been an ongoing quest. Local dimming was created in an effort to make LCDs appear to have a similar contrast ratio to plasmas. The best of these do a pretty good job. OLED’s great claim to fame, its breakthrough, if you will, is in delivering remarkable, infinitely inky blacks.But even OLED, as impressive as its contrast ratio is, still doesn’t look like a window on the world. It’s close, certainly closer than we’ve ever gotten with any other technology, but it’s still a “TV.” Why is that? It’s because, even with unmeasurable black levels, the brightness of highlights in our current televisions still can’t mimic real life.

Dolby and several other companies aren’t just aware of these limitations; they’re actively working on a solution. What they want to do is really push that envelope of brightness and black level, expanding the contrast ratio into something they call High Dynamic Range.

An Acronym You Can Love

Imagine you’re outside on a sunny day. (Terrifying, I agree, but stay with me here.) You look down the street, along a row of cars. The sunlight reflects off the windshield of one, dazzlingly bright. On the side of that car, the tires are in shadow. Your eye can see both the intense brightness of the reflected sunlight and the comparatively dark area where the

tires are.

A TV with a high contrast ratio will show that scene pretty well: bright reflection, dark shadow. A TV with a poor contrast ratio will show either a bright reflection and a bright gray shadow, or a dim reflection and a dark shadow—that is, not high brightness and deep black level at the same time.

Another example: It’s night, and you’re walking along a road. A car comes around a corner with its high beams on. A high-contrast TV will be able to show the bright lights and keep the background dark, while a low-contrast TV will have to make a choice between the two.

Enter HDR. Imagine a TV that, in the first example, shows the shadowed tires but can still display the reflected sunlight as genuinely bright. Like it would be in real life. Or imagine a picture in which those high beams truly pierce the darkened screen around them.

How bright are we talking? Well, if you have an LED LCD at home, and you crank up the backlight, you can probably get around 100 foot-lamberts of brightness on pure white highlights. Plasmas, which make their own light and don’t have the benefit of LEDs to drive the picture, produce less than half that. The folks at Dolby, with their Dolby Vision HDR technology, are talking about a TV capable of 5,837 ft-L (or, as they say it, 20,000 nits).

HDR is the same idea idea as local-dimming LED LCDs but a few steps beyond. Think of it as local dimming on meth.

Now, I can hear you already: “OMG, it burns, it burns, turn it off.” You, my recently singed and blinded friend, would be correct. A TV that puts out a continuous 5,837 ft-L would be unwatchable anywhere but on the surface of the sun. Probably not even there—not without a welder’s helmet and some Perrier.It all comes back to contrast ratio. That’s what the real story is. The idea of HDR is not to make an ultrabright TV—at least, not in and of itself. The idea is to make a TV with enough headroom to create truly bright highlights, while at the same time creating inky deep blacks. So to use the first scenario I mentioned, the average across the entire screen might be 30 ft-L, with the shadowed tires around 1 ft-L but the small area of the reflected sunlight 200 ft-L or more. In the nighttime scene, the blacks in the sky would be as close to 0 ft-L as possible (no light), but the bright headlights—and just the headlights, mind you—could be 100 ft-L. These numbers are just examples, but I think you get the idea. Basically, it’s an image that mimics what you would see in real life, not an image created by a screen in your den.

You may be wondering about “regular” local-dimming LED LCDs—what you’ve seen in stores, in these pages, or perhaps in your home right now. HDR is the same idea but gone a few steps beyond. Think of HDR as local dimming on meth. Maybe more than that. Meth and melange.

The Signal

Creating an HDR TV is great, but what about improving the content? This is the other aspect of what Dolby calls its Dolby Vision concept. They want to improve the video signal to make sure the content supports what an HDR display could do. This is no trivial endeavor. Much of our current content is still created within confines established by the limitations of CRT televisions.

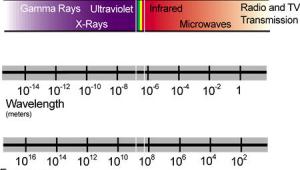

Notably, Dolby hopes to expand the video signal’s color gamut and bit depth. The same types of enhancements are under serious discussion by those considering the future of Ultra HDTVs, apart from the 4K resolution that is its current primary selling point. Color gamut determines the range of colors possible in the signal. Current TVs, bound by the HD color spec Rec. 709, don’t offer nearly the rainbow of fruit flavors visible to the eye. For example, the deepest reds, a decent purple, and many other colors just aren’t possible. As part of Dolby Vision HDR, Dolby wants to have richer colors available on the painter’s palette for film and TV directors.