Steven Wilson Dissects His Latest 'Home Invasion'

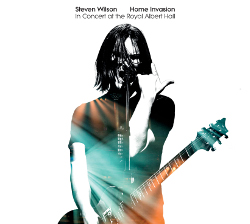

The once and future king of surround sound has duly surveyed the live landscape that’s been laid out before him, and hath found it to be good. I’m talking about, of course, 5.1 guru Steven Wilson, and his just-released Home Invasion: In Concert at the Royal Albert Hall (Eagle Vision) once again pushes the multichannel envelope on Blu-ray, as one might expect. (Home Invasion is also available on DVD+2CD, and, coming in early 2019, 5LP 180-gram vinyl.)

As an artist who has logged a number of live releases over his career, both as a solo artist and dating back to his earlier days with the seminal prog-leaning British collective Porcupine Tree, Wilson feels the need to continue changing how he approaches each performance. “Well, you know me, Mike — I’m always looking for a different way of doing things so that it excites me,” Wilson told me. “And I want to feel like I’ve raised the bar. That applies to the recorded work, and that applies to the live show — otherwise, there’s no point. Doing more of the same thing is pointless to me. Every project needs to have its own identity, and I want to feel like every project is an evolution.”

I called Wilson, 50, across the Pond to discuss the differences between mixing live quad for a performance venue and then mixing the same show for home release, the importance of creating dynamics and tension release, and how to keep an audience engaged for 3 uninterrupted hours. You’re still here, and you’ll dig in again. . .

Mike Mettler: You’ve played at the Royal Albert Hall a few times before, both as a solo artist and with your former group, Porcupine Tree. You obviously feel some sort of comfort factor with that venue, which made it an easy choice for you in terms of where to record this show.

Mike Mettler: You’ve played at the Royal Albert Hall a few times before, both as a solo artist and with your former group, Porcupine Tree. You obviously feel some sort of comfort factor with that venue, which made it an easy choice for you in terms of where to record this show.

Steven Wilson: I think I’ve done it seven times now. I did it once with Porcupine Tree [on October 14, 2010], and six times now as a solo performer, which is amazing.

Something people forget is that my former group didn’t really get to the point I have with my solo career, being able to sell tickets like this. I did three nights at Albert Hall this time [March 27-28-29, 2018], and all of them sold out, so I can’t think of a better place to have filmed the show, for sure.

To be honest, people have asked me over the last two or three albums, “Are you going to film a concert?” And I’ve been quite reluctant in a way, because there’s something about filming a show and trying to capture that spectacle in terms of that whole cinema screen. There’s something that’s inevitably compromised in doing that.

But when the proposition came through this time — the idea that we would film the third night of a Royal Albert Hall run — that made sense to me. Firstly, it’s the third night of three, so the band is hopefully quite comfortable by then in terms of the feeling onstage, and the dynamics with the audience and what you feel onstage having done it two nights before already. Secondly, it’s such a fantastic venue, and thirdly, it’s my hometown! It’s like a hometown show for me. Well, it isn’t like a hometown show — it is a hometown show!

Mettler: You and David Gilmour can give Eric Clapton a run for the number of sold out shows you ultimately do at the Albert Hall.

Wilson: Yeah, I mean, David always does multiple nights there, and Eric Clapton always does multiple nights. It’s very interesting when you look at those kinds of artists who could be doing stadiums if they wanted to, but they prefer to do 10 or 12 nights at the Albert Hall. That’s not surprising in a way, because it’s such a magical feeling onstage at that venue. There’s definitely an atmosphere that hopefully translates across in the live concert film. It has that kind of strange paradox of being a big venue, but at the same time still has this wonderful intimacy about it, because the audience is all around you.

Mettler: From the onstage vantage point we get to see in the film, it looks big but doesn’t feel big, which must also affect the way you interact with the people all around you.

Wilson: Very much. You can literally look everyone in the face. Most places where you play to 3 or 4,000 people, the guy in the back-back row is literally half a mile away. So that does make a big, big difference inside the venue when you’re onstage.

Mettler: Did knowing this venue so well already temper how you decided to set up the way you were going to record the show, in terms of where the mikes were positioned and how the quad speakers were placed?

Wilson: Honestly, I would love to tell you I gave it lots of thought, but I didn’t, really, because I knew that the show would lend itself to a good surround mix anyway. There are a number of things in the venue already programmed to come from the rears — and obviously, we wanted to emulate that in the mix and in the cinema version too. But there’s also other stuff coming from the rears that weren’t necessarily coming from the rears during the concert.

The difference when you mix quad for a live concert is there’s no way everybody in the venue can be in the sweet spot. Somebody is literally going to have their head in the rear left speaker and somebody’s going to have their head in the one in the right corner, so you can’t really put too much emphasis on the surround. I think you have to be a bit more careful, and a bit more subtle, about how you employ it.

Things that tend to work best live in the quad are the sound-design elements — sound effects, textures, backing vocals. You wouldn’t put rhythmic things in the rear speakers in a live concert, for example — with the time delays, you’d be creating a real issue if you did that.

But obviously, mixing it for the home cinema is a different thing. You can be a bit more bold and a bit more brave in what you position in those rear speakers. I think we can say the home cinema mix is a bit more aggressive and more discrete than the quad mix you’ll hear in the live concert hall.

Mettler: You’re always good at dealing with varying levels of volume in your live shows. Some songs start out quietly and then build up almost cacophonously, then they dial right back into quieter elements. There’s a clarity in the music the band is playing during those moments that a lot of artists don’t quite understand how to harness without it becoming some kind of muddy wash. Being a master of volume manipulation is something that must be very important to you.

Wilson: Yeah. And lest anyone forget, dynamics is a big part of music, and space also plays a very big part in the texture and the very fabric of the music. We can talk about it in relation to the concert film, but I like to think that’s something that’s been a part of my work, a very signature of my work, right from the very beginning — that I love dynamics and that I love the idea of that journey, sometimes within a single song. And by “journey,” I don’t mean the band (both chuckle), but in terms of the range of emotions, changing textures, and sometimes even changing musical styles within the same piece of music.

I love that. I love that almost cinematic approach to creating music where it’s almost like scenes, and you’re telling a story through a series of scenes. Some scenes are going to be very quiet and everyone’s going to be very mellow, and then the next scene, someone is going to be very angry. Those are the sorts of dynamics you get from films, and that often applies to the way I make music. I love to build tension, and I love to release tension. I think that’s always been fundamental to the music I’ve made over the years.

Mettler: Agreed. Especially throughout this set, it’s almost like you’ve created a sine wave for how it evolves over almost 3 full hours with specific peaks and valleys. For me, the back-to-back impact of “People Who Eat Darkness” and “Ancestral” is something that shows exactly what we’re talking about here.

Wilson: Yeah, and I think it’s partly pragmatic as well, because you’re thinking, “Well, I’ve got to keep this audience entertained for close to 3 hours.” If you just have a constant mode that’s static, people’s concentration is going to start to wane. Even if they like what you’re doing, if you’re just bombarding them with the same kind of texture and dynamic for 3 hours, people are going to lose interest.

It’s really a question of keeping people’s attention by constantly changing the dynamics of the mood, changing the atmosphere, going from quiet to loud or pop to progressive, or playing metal riffs — all of which is part of my music. It’s as much part of my trying to keep the audience interested for what is a pretty big chunk of time. If I just went out there and played a whole evening of 10-minute epics, a whole evening of pop songs, a whole evening of singer/songwriter material, or a whole evening of bludgeoning metal riffs, I think that’s where you’d lose people. You have to change it up.

And you pointed out a good example — that change from “People Who Eat Darkness” to the very atmospheric, textural opening of “Ancestral.” That’s as much about getting people’s attention back again after a 6-minute punk-rocker song, you know?

Mettler: That’s a good point, because as an inveterate concertgoer myself, there comes a time at certain shows where I think, “I need some sort of break to catch my breath.” Being assaulted for 2 full hours makes it hard to get into a show on that deeper connective level.

Wilson: I feel that way sometimes about albums. Generally, I love hearing a couple of wind-out songs from an artist, but then I may feel the rest of the album is just more of the same, or just variations on the same musical vocabulary. I think partly that’s why I’ve always been attracted to, ever since I was a kid, those more conceptual rock albums that my mom and dad used to listen to, as we’ve talked about before. Those albums felt more like the artists were exploring different aspects of music. To me, albums where you get ten full-on assaults — I can’t concentrate on those for very long. And it’s not just about the show itself. It’s more of a general feeling, or a more general approach I have to making music — to keep changing things up as much as possible. And that’s partly to keep me interested as well.

Mettler: That’s true, and that also speaks to the lost art of sequencing 40 minutes for an album, as opposed to 80 minutes. You’re telling a story, even if it’s not linear, where you still need to take people through changes of feeling, and affect them all across that period of time — or else they may not even stick with it the whole way through.

Wilson: Right, and the more timespan you need to fill, the more you need to think about that. What happened when CDs came along is that albums got longer and longer, and people became less good at sequencing them, and they became even more tiring.

And it’s funny — so many of the classic albums, the ones that have held up year after year, seem to come from the vinyl era, not the CD era. And I think there’s no coincidence that as CDs got longer, people became more fatigued by them.

Again, I have to reiterate that this is close to being a 3-hour show, so I really had to think, “How am I going to keep people engaged for that long?” And I don’t know if I do or not, but I certainly had a good crack at it.

Mettler: Oh, I think you did quite a fine job of it. You also have to keep us engaged visually, so I’m sure you were very hands-on with those film-related decisions as well.

Wilson: I wasn’t as hands-on in the final editing, but the one thing I did encourage the guys to do was, “Don’t feel like you can't use cinematic techniques.” For a lot of concert releases, the artist will say, “I just want the band to be portrayed very straight,” but I said, “No. You know what? If you want to use slow motion and animation, if you want to use different images laid on top of each other, if you want to use split-screen or blurring — do it.” Because this is a concert film, with the emphasis on film. And I don’t see any problem in using cinematic techniques. It doesn’t have to be “purist,” in this case.

Mettler: Did you give them [director James Russell and editor Tim Woolcott] any specific filmic touchstones for what you were trying to achieve?

Wilson: I’m not sure I gave them examples, but what I remember was, when I went down to see the first cut they had done, I saw they had hinted a little bit at that. And I said to them, “Do more of that. We need more of that.” And what they said to me was, “We were being very careful because a lot of artists don’t like it when we put those kind of things in.” And I said, “No, I love it! Do more of it. More of the blurring, more of the split-screen, more of the slow motion, more of the overlay. To me, this is more about keeping people interested for 3 hours, and making it a very cinematic experience.” I think it was more of a question of me encouraging them to do more of what they were already hinting at so that the film definitely became more cinematic by the end.

I’ve never made a live performance film quite like this before. It is very cinematic, and that cinematic approach stems partly from the show itself, which is probably the most cinematically spectacular thing I’ve ever presented.

Mettler: After I saw it live in New York, I remember thinking to myself that I would need to see it a couple more times just to catch everything that was going on, because there were multiple elements not only in terms of what I was listening to, but also what I was observing onstage, and what was projected on the scrim and what was behind you as well. You’d given us a number of options for what to focus our attention on.

Wilson: To me, that’s a fundamental thing, and I again go back to those albums I loved as a kid — this idea that you needed a reason to go back and listen to things two, three, or even 50 times. If you got everything you were going to get out of it the first time through, that didn’t necessarily reflect very well on the art. I believe the best art has got layers, and that it has something that keeps you coming back to it time and time again. It’s a very intangible thing, but I like to think what I do has that kind of quality to it.

Mettler: I always think of the way you like to change things up. In one of the Blu-ray-only bonus features, the song with the now ironic title of “Routine,” we get to both see and hear how that song has gone through a number of permutations as you’ve performed it over the years.

Wilson: It’s actually really beautiful because we shot it in the empty venue on the afternoon of the show, and the venue almost becomes a part of it — the Albert Hall, with no one in it. Some of the angles the camera captures for that are a little bit eerie, but it suits that song really well.

Mettler: Last thing — recently, a high-grade vinyl Yes box set came out with your name on it, The Steven Wilson Remixes. Did you ever think you’d become, well, a brand?

Wilson: No! But I guess I am, in a way. I just wish they had asked me before they did it (laughs), but, hey, whatever. I suppose that’s flattering in some way, yeah, but listen — one thing I’m proud of is that if my name is attached to a remix project, I do think people now have a certain expectation of quality. I don’t do remixes or surround mixes as much as I used to because I’m busy with my own career, but if I do do them, it’s because I love the music first, and secondly, I think I can do a good job.

That’s something I hope I’ve earned, and you know what? That’s why I keep doing it — because people seem to like it, and they like the way I’m doing it.