Speakers Are A Lot Like Dinosaurs

No doubt about it — speakers have come a long way, and continue to get even better. The range of speaker options is staggering: You can choose anything from diminutive satellites to mighty towers, skinny soundbars to rotund subwoofers. If you can’t find the speaker that exactly fits your needs, tastes, and budget, then you just haven’t looked hard enough. But — and I take a deep breath here — speakers are a lot like dinosaurs.

They rule the earth, but maybe they’ve been around for a little too long, and maybe it would be best for everyone if a giant comet just finally wiped them out. I can see the hate mail filling my inbox already. Yes, I agree that speakers can deliver truly outstanding sound reproduction. Yes, I know that speaker engineers are among the most innovative and progressive folks around. No, I don’t have an alimony-hungry ex-wife who’s a speaker designer. But — another breath — in today’s technoworld, speakers are anachronisms. The first moving-coil speaker was devised in 1898 and significantly improved in 1924. Since then, all other audio technology has rocketed forward. But the essential design of the speaker hasn’t changed. Many very clever alternate designs, such as electrostatic speakers, have been invented. But most speakers still use the 19th century moving-coil design, with incremental improvements appearing over the next 111 years. That’s kind of like riding around in a tricked-out horse and buggy.

In all fairness, speakers have a tough job. Much like the larynx, two hands clapping, and everything else that makes a sound, a speaker must move air. In particular, it must convert an electrical signal that represents a sound into the sound itself. Most speakers use a linear motor to do it: The signal powers the voice coil, which moves a cone, which moves the air. That’s nowhere as easy as it seems. For starters, the process is enormously inefficient. Also, those pesky laws of physics insist on being observed.Even worse, speakers don’t directly benefit from the most important fruit of recent technological innovation — the computer. Sure, speaker designers use computers to model and study their creations, but speakers themselves can’t use tiny silicon minds and software to move air more efficiently or accurately. Like dinosaurs, they have tiny brains and survive mainly on brute strength.

As the ultimate sign of their perceived backwardness, speakers are now culturally unacceptable. Back in the day, manliness was directly determined by the height of your (two) speakers. Every young boy longed for the day when he too could precisely align two big towers in his room. Now way too many speakers are designed to be tiny and unobtrusive and to “blend in” with the room décor, as if it’s embarrassing to actually have speakers in a room, as if their presence would somehow distract from the enormous TV. Even worse, and much to the chagrin of speaker manufacturers, too many listeners are forgoing speakers altogether and instead jamming cheap little transducers into their ears. How humbling for once-mighty speakers — to be downgraded into plastic things the size of a pinkie.

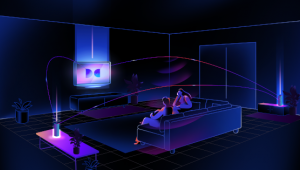

So what will become of speakers? Will some clever engineer devise a startling new way to move air? Or will we abandon this essentially hopeless endeavor altogether? Maybe with enough computing power and software and some newfangled neurochemistry, we’ll figure out how to beam sounds directly into our brains. Imagine a home theater system without any traditional speakers at all. Instead, you’re listening to full-tilt sound in a completely acoustically silent room as the system taps into some mental wavelength. Or consider an MP3 player free of tangled cords — and absolutely nothing in your ears. In that future world, all electronic sound, reproduced or live, would be beamed directly into the cranium. The efficiency and accuracy of such future technology would render obsolete the need to transduce electrical audio signals into moving air. The only audible sounds would be from natural sources like crickets, birds, and orchestras on stage.

Well, maybe someday. Meanwhile, we’ll have to rely on speakers to connect us to the world of electronic sound. Some important points in favor of their backward simplicity: No matter how old the technology, speakers will never crash, their software license will never expire, and their motors, which go nowhere except in and out, will never fail to boot. Whew! Can you imagine if we were suddenly unable to access all recorded sound? Thanks to trusty speakers and the vital role they play, we’re safe from that calamity. Sometimes it’s good to be a dinosaur.

-- Ken C. Pohlmann

- Log in or register to post comments