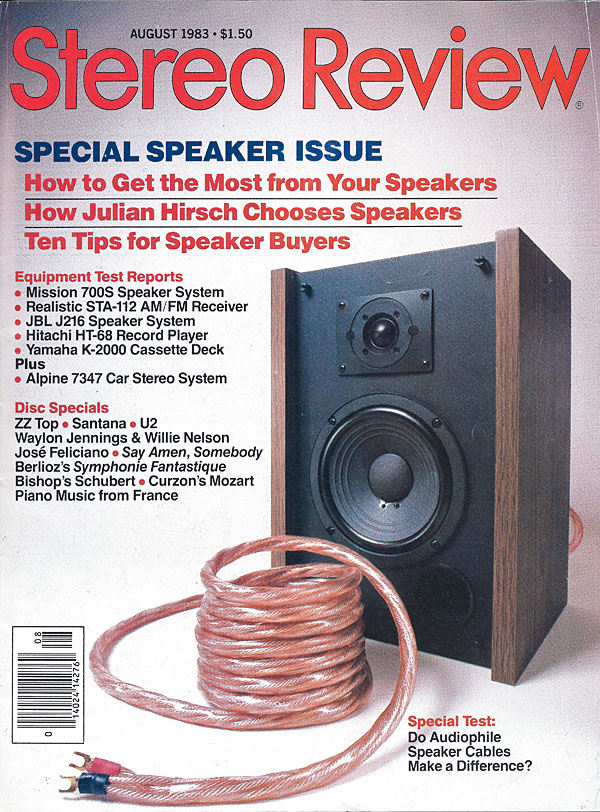

Speaker Cables: Can You Hear the Difference?

Editor's Note, 2018: In the early 1980s, esoteric high-end audio as we know it today was just taking off as an alternative to the mass-market equipment offered in neighborhood TV/appliance stores. Fueled by an underground audio press that included magazines and newsletters such as Sound & Vision sister publication Stereophile, The Absolute Sound, International Audio Review, The Audio Critic, and others, a cottage industry emerged, one populated by small manufacturers of low-volume, high-priced exotica claiming greater faithfulness to the music than the gear reviewed and advertised in the pages of Stereo Review, High Fidelity, Audio, et al. Some of these claims were founded—true advances were indeed being made by start-ups run by technicians with first-class bonafides and good ears. But the High End also attracted its share of half-baked products and at least a few charlatans looking to cash in selling accessories that had little higher performance than a dime-store engagement ring.

Editor's Note, 2018: In the early 1980s, esoteric high-end audio as we know it today was just taking off as an alternative to the mass-market equipment offered in neighborhood TV/appliance stores. Fueled by an underground audio press that included magazines and newsletters such as Sound & Vision sister publication Stereophile, The Absolute Sound, International Audio Review, The Audio Critic, and others, a cottage industry emerged, one populated by small manufacturers of low-volume, high-priced exotica claiming greater faithfulness to the music than the gear reviewed and advertised in the pages of Stereo Review, High Fidelity, Audio, et al. Some of these claims were founded—true advances were indeed being made by start-ups run by technicians with first-class bonafides and good ears. But the High End also attracted its share of half-baked products and at least a few charlatans looking to cash in selling accessories that had little higher performance than a dime-store engagement ring.

In the midst of all this, the premium cable business emerged, driven in no small part by the success of the early Monster Cable products that followed the company’s founding by engineer/audiophile Noel Lee in 1979. The editors of our precursor Stereo Review were suspicious of the benefits of such speaker cables and interconnects, which were suddenly being proffered by an ever-widening mix of high-end specialists, often at prices far higher than Monster’s. The highly objective measurement-based testing approach employed by Julian Hirsch and his colleagues already ran counter to the high-end community’s subjective reviews, which focused solely on claimed sonic differences that SR’s instruments couldn’t detect. It wasn’t long before Stereo Review began positioning itself as the skeptical voice of reason in what its editors deemed an audio industry gone mad.

It was no surprise, then, that in 1983, the magazine jumped at the opportunity to conduct a double-blind listening test, which editor-in-chief Bill Livingston and his colleagues hoped would reveal, scientifically, that high-end cables were indeed a hoax and provided no higher performance than the everyday lamp cord in common use at the time. The pitch was made by accomplished research psychiatrist Laurence Greenhill, an active member of the Westchester (county) Audiophile Society based in the New York City suburbs, and a reviewer for the audio journal High Performance Review. Greenhill’s science background and personal interest in acoustic perception and subjective listening had led him to write some articles on these subjects, and eventually to fascination with a new audio testing device called the ABX Double Blind Comparator System. This box (as explained in Greenhill’s article) used logic circuitry to randomly trigger relays that allowed listeners to compare two unknown sources instantaneously while eliminating the need for (and therefore, the bias of) a test administrator to select the sources; hence the term double-blind. The system had been developed by members of the Southeastern Michigan Woofer and Tweeter Marching Society, a DIY hobbyist group out of the Detroit area (of which former long-time Stereo Review contributor Tom Nousaine was an active member).

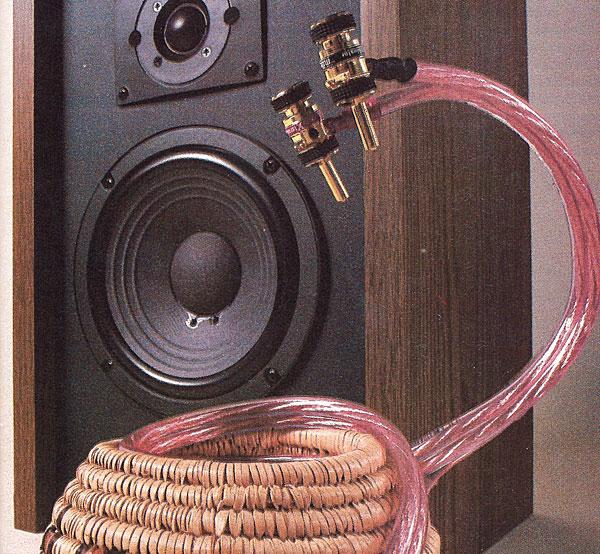

By chance, Greenhill lived a few miles away from Hirsch, and their casual acquaintance provided the entrée. The SR editorial team worked up the test protocol with Greenhill and some Audiophile Society colleagues and Marching Society member/ABX officer David Clark. To keep things from getting unruly, they settled on testing three speaker cables at 30-foot lengths, including thin, 24-gauge of the type found at electronics outlets; 16-gauge lamp cord bought at a hardware store; and 11.5-gauge Monster Cable to represent the premium segment. As the most visible and successful purveyor in the category, Monster was an obvious choice, though, as Greenhill told me recently for this article, it’s noteworthy that Monster’s early speaker cable was essentially also twisted-filament copper like the other test subjects, with nothing particularly advanced in the cable design compared with later products that came from Monster and other manufacturers. An 11-member listening panel was recruited largely among experienced high-end audiophiles from the Westchester Audiophile Society, with Greenhill’s own young son and another high-schooler filling out the mix. The 50 hours of tests were conducted in Greenhill’s personal listening room with equipment borrowed from manufacturers.

The resulting article created a firestorm. As you’ll read, the panel identified, to a statistically significant degree, the 24-gauge from the other two contenders with pink noise as the source. More critically, they also identified, again with statistical significance, the Monster Cable from the 16-gauge with pink noise. But the latter results didn’t hold when choral music was used, and none of the Monster versus 16-gauge results passed the higher threshold of a 75 percent or greater detection rate said to be psychoacoustically significant.

Interestingly, it was not the results of the test (which were mixed, after all), but the article’s written conclusion that set off so much heated discussion. As originally submitted, Greenhill’s balanced conclusion acknowledged that the panel had indeed heard statistically valid differences, at least with pink noise, and that the test should be seen not as a blanket result for all audiophile cables, but simply as research on these three, largely similar test subjects that were distinguishable mostly by level changes easily associated with gauge. SR’s editors, however, rewrote the ending to create something akin to a blanket condemnation of the category and pressured Greenhill to accept the changes, a decision he later regretted. “They felt my conclusion didn’t grab the reader as it should, but that was my point,” Greenhill recalled. “I wanted to conclude that this test wasn’t a fair judge of all cables, but revealed you could tell level differences based on the size of the cable. They wanted it to be a condemnation of [high- end] audiophiles.” (You can read Stereophile’s description of the controversy on stereophile.com; search for “The Horse’s Mouth.”)

The article as published was picked apart and attacked by the high-end press, and the Monster Cable company, not unreasonably, felt unfairly maligned as expressed in a letter to the author from Noel Lee. Greenhill, for a time, became a pariah in the high-end community, though he continued reviewing and has for many years been a regular contributor to Stereophile. He now lives in California and, at 76, is still a practicing hospital physician and a teacher at the University of California, San Francisco. Today, 35 years later, the debate over audiophile cables remains as active as ever.—Rob Sabin

The Original Article from 1983:

Some audiophiles believe that the seemingly innocuous wires used to connect stereo amplifiers to loudspeakers actually have a considerable effect on a system’s overall sound quality. Unsatisfied with the performance of 16-gauge heavy-duty lamp cord or “zip” cord (“gauge” is a measure of thickness; the lower the number, the thicker the wire), these purists install exotic, expensive, and physically imposing cables instead. A 30-foot run of special audio cable may cost anywhere from $55 (for a pair of Monster Cables) to more than $300 (for Levinson wire). After purchase, these thick and massive wires are terminated with special lugs or pressure-fitting banana plugs ($25 per pair), coated with a contact cleaner (Cramolin), and installed with loving care.

Does it make any difference? Is all this trouble and expense necessary to achieve the best possible sound? The editors of Stereo Review have long maintained that for normal home cable runs (in the 20- to 50-foot range) to 8-ohm speakers, 16-gauge zip cord provides optimal power transmission between a system’s amplifier and speakers. The “official” view has been that heavier and/or more expensive audio cables represent—for ordinary home installations—electronic overkill.

Nevertheless, equipment-oriented audio hobbyists have continued to tinker and experiment with their systems’ connections. Quick to respond to a felt need, audio manufacturers have filled the marketplace with a variety of exotically named wires: Discwasher Smog-lifters I, AudioSource UHD, Live Wire 301X4, Mogami Neglex 2477, Oracle Leonische, Fulton Golds, Monster Power Line, Big Red Live Wire, and so on. Is this just another case of the mystique and glamour of high-end audio inducing otherwise sensible music lovers to waste their money? Or is there some real sonic advantage to using audiophile speaker cables?

Our view is that if there are audible differences among speaker cables, they probably derive from measurable differences in their respective electrical properties. Nelson Pass of Threshold Corp., for instance, claims that subtle sonic differences can be correlated with differences in electrical resistance, capacitance, and inductance, which vary according to overall cable length. And these factors can result in measurable differences in frequency response and signal level, depending on the particular speakers and amplifiers the cables connect. But the measurable differences in electrical characteristics and performance between audiophile cables and cheaper, 16-gauge zip cord seem too small to explain the apparently huge audible differences that are sometimes reported.

Just how different in electrical characteristics do cables have to be before there are audible effects on frequency response and signal level? In order to answer this question, among others, we embarked on a series of laboratory and listening tests. Because of logistical, time, and budget restrictions, only three cables were exhaustively tested: (1) 16-gauge heavy-duty lamp cord, purchased from a suburban hardware store for 30 cents a foot; (2) 30-foot lengths of New Monster Cable, costing $55 a pair; and (3) 24-gauge “loudspeaker cable,” available from many sources at about 3 cents a foot.