Robbie Robertson on the 50th Anniversary of The Band’s Music From Big Pink

There are certain albums of the 20th Century that get anointed as having been the ones that changed the world, altered the nature of the overall sonic landscape, and/or influenced generations of musicians past and present — and then there’s The Band’s Music From Big Pink.

Released 50 years ago this past July 1, Big Pink immediately set the world of popular music on its collective ear. In the swirling midst and mists of psychedelia, hard rock, and acid rock, Big Pink was a literal breath of rustic fresh air, seemingly dropped onto the music scene from out of nowhere — even though it was mostly born and bred in the basement of a cozy little rosy-hued house in upstate New York (one that frequently entertained a certain motorcycle-injury-recovering songbard as a regular creative contributor to the proceedings). Over the course of its 42 minutes, Big Pink both reintroduced and expanded upon the notion of songwriters telling stories at their own pace and bandmembers seasoned by sharing many years on the road together playing their own original music intimately and intuitively.

To celebrate this most singular achievement, Capitol/UMe has just released The Band’s Music From Big Pink – 50th Anniversary Super Deluxe Edition, which features six bonus tracks, two 45rpm 180-gram LPs, a 7-inch single, collectible lithographs, and, of great interest to us here in the audiophile community, a 5.1 mix of the entire album and said bonus tracks in 24/96 on Blu-ray by Bob Clearmountain (Bruce Springsteen, The Rolling Stones, Simple Minds) and The Band’s chief songwriter and guitarist, Robbie Robertson.

To celebrate this most singular achievement, Capitol/UMe has just released The Band’s Music From Big Pink – 50th Anniversary Super Deluxe Edition, which features six bonus tracks, two 45rpm 180-gram LPs, a 7-inch single, collectible lithographs, and, of great interest to us here in the audiophile community, a 5.1 mix of the entire album and said bonus tracks in 24/96 on Blu-ray by Bob Clearmountain (Bruce Springsteen, The Rolling Stones, Simple Minds) and The Band’s chief songwriter and guitarist, Robbie Robertson.

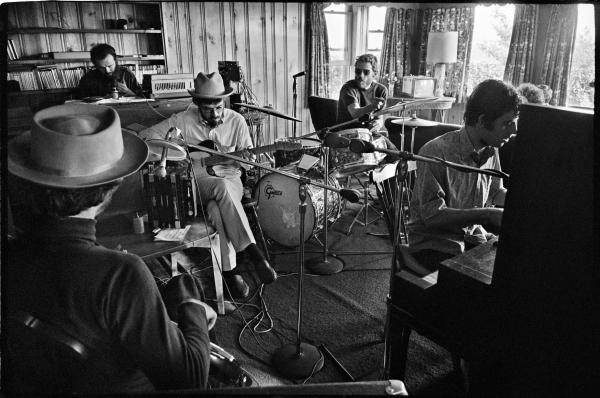

“I wanted to make music that sounded like it’s its own thing,” explains Robertson, seen seated above amidst his Band-mates with his legs crossed and guitar in hand in a classic, copyrighted Elliott Landy photo taken in Woodstock, New York in 1968. “It isn’t just about the playing — it’s about the atmosphere. Certain studios, whether it was Sun Records [in Memphis], Chess in Chicago, EMI Studios at Abbey Road, Muscle Shoals [in Alabama], or whatever — all these places had their own character. All of them. And I was like, ‘I don’t want their sound — I want our sound!’” Without a doubt, Music From Big Pink captures all of those intentions to a T. (Or should that be a B. . .?)

Robertson, 75, and I got on the line to discuss the secret to the overall closeness of the Big Pink recording itself, the key elements that make the 5.1 versions of “The Weight” and “Chest Fever” instant benchmark reference tracks, and what Band album he’d be interested in having remixed in 5.1 next. I see my light come shinin’. . .

Mike Mettler: When we spoke about surround sound back in March 2011, you said, quote, “I love the idea of putting the listener right there so he can sit in the middle of the people playing the music, like he’s in another chair in the room with them.” That being said, I have to imagine you and Bob [Clearmountain] are super-pleased with what I think is a fantastic surround mix for Big Pink.

Robbie Robertson: I love it! I love it. And I so appreciate the idea that, the closer you can get to being right in the room, right in the center of the music, closing your eyes and feeling what everyone else was feeling playing that music — I think that that’s a special gift.

Mettler: And Music From Big Pink is only a 4-track recording, right?

Robertson: It is! I mean, the limitations of that, and the way you look at it now is just. . . (slight pause) it’s extraordinary. Because the decisions that had to be made on the spot, for forever, and that we’d be talking about them 50 years later, is — it’s unimaginable to me that what we were able to do that. And I don’t know if we were just really smart about it and really knew what we were doing — or we were just very lucky! (chuckles)

Mettler: I think it’s a combo platter. The way that you tell it in your book, [his November 2016 autobiography] Testimony, in Chapter 19 on page 293, you specifically say to [original Big Pink producer] John Simon, “Okay, we need to have a unique sound. The album needs to have a flavor all its own.” When you guys get to the recording studio in New York [A&R Recording], you were smart enough to say, “Hey, we’ve got to take these baffles down so that we can look at each other.” That was the key, right?

Robertson: Well, it was the only way at that point where we had evolved to musically that we could do what we did. It wasn’t trying to be “different,” it wasn’t trying to be “rebellious” — it was really just about trying to find a way that we could do what we needed to do to make this particular music, and this particular sound. And it was a rebellious thing when you talk about it, but it wasn’t meant that way. We were trying to musically survive — sonically, and just the way we played to one another.

If I couldn’t see somebody’s eyes, if I couldn’t see them lifting their chin to tell me something at a certain point, if I couldn’t signal something with my guitar neck, or I couldn’t nod at somebody right at the moment a break was going to be coming — all of that stuff was integral to the nature of this music that we were making.

Mettler: “Tears of Rage” was the first thing you guys cut in that New York studio. Was there one specific moment after you guys took the baffles down and you knew you were on the right track? [“Tears of Rage,” the first track on Big Pink, was co-written by Richard Manuel (melody) and Bob Dylan (lyrics).]

Robertson: No — when we took the baffles down and we set up in the way that we felt comfortable, the recording engineers [four of them in total: Don Hahn, Tony May, Rex Updegraft, and Shelly Yakus] thought that this was disastrous. And John Simon, he kind of saved the day. They [i.e., the engineers] were saying, “We can do this, but’s it’s gonna sound terrible. The leakage is going to be ridiculous. For everything that we do in this studio, this is exactly what doesn’t work.” When John suggested we use these certain microphones —

Mettler: The Electro-Voice microphones?

Robertson: Yes, these Electro-Voice RE15 microphones, which we used on just about everything. They [the engineers] were like, “But they don’t sound any good! You want to use them on vocals? You want to use them on the drums, on the bass? That’s crazy!” And he [John Simon] said, “We gotta try. We’ve gotta try.”

With all of these stipulations that we imposed on these engineers, they started to find something in that — and this turned out to be a gift, because it made a unique sound. It made this album be something apart from everything else that was going on in music in the world.

And this could have not worked, too. It could have been terrible! But we did do this, and we got to a place where we could see one another, hear one another in the room — and not in headphones — we were in the room beside each other, and we could make music to one another, to each other, looking around the circle — we knew we were in our comfort zone, and we knew this was real to us.

Whether it could be translated to microphones onto a tape machine (chuckles) — that was a complete mystery, and a question. After we got a pretty good balance on everything, John Simon says, “Guys, we’re getting somewhere on this.” When we put down “Tears of Rage,” he said, “I think you should come in here [the control room] and hear this.” And the engineers were saying, “This is really coming together, to our surprise.”

We went in and heard it, we said, “That’s who we are. That’s how we sound.” Listening through the studio speakers, that was the first time we had heard what The Band sounded like.

Mettler: Amazing. And Phil Ramone was there too [the legendary producer who was co-owner of A&R Recording studios]. He came in, heard it, and understood that the methodology you were using was how you guys had to do it.

Robertson: Phil Ramone came in, saw the setup, and thought it was ridiculous. And then we played him a couple of songs, and he said, “If it sounds good, then that’s all that matters.” He said, “This is incredible-sounding! Believe it or not, I thought I knew how to do this, and you just taught me a lesson.” You had to be grateful for those kind of moments.

Mettler: Yes, and it’s been proven again in the 5.1 setting. Graham Nash and I once talked about this. He’s also very passionate about surround sound, and he told me he wanted it to be like you, the listener, was standing next to him while he was singing: “You need to be right next to me for you to get the feeling I want to get across to you.” And it sounds like you and Bob [Clearmountain] have worked together to get this mix to where I feel like I’m sitting there where Rick [Danko, bassist] and Richard [Manuel, pianist] are looking at each other, and the rest of you guys are too. I feel like I’m right over your shoulder, if you don’t mind me being there. (chuckle)

Robertson: Well, what Bob and I did, with us going back and forth with these mixes, is we wanted to arrive at a place that felt like complete satisfaction — to not getting in the way, and doing everything that we could to invite you closer and closer to the emotions in this music. What a fantastic experience, 50 years later! And, what it turned out to be, to me, is a total experience in sound and vision. I can see the music, as well as hear it.

Mettler: I think so too. That’s why we’ll have to name the magazine after you for that idea.

Robertson: Yes! (chuckles heartily)

Mettler: And obviously, “The Weight” is a song that very much fits its title. The staggered “and” vocal choice you made for the three vocalists just gave me chills as I heard that unfold in the surround mix. You had to make sure those three vocalists hit it just right. [The three singers on the song, drummer Levon Helm (first three verses) and Rick Danko (fourth verse), who share lead vocals, and Richard Manuel, who sings background vocals, each take a turn singing the word “and” before they all join together on the rest of the line that follows, “. . .you put the load right on me.”]

Robertson: And we didn’t really get that arrangement figured out until we got into the studio. As I have said before, I didn’t know if this song was going to make the cut. It was kind of a backup song I had written, but I believed Levon could sing this song to pieces, and I had wanted so much to write something just terrific for Levon. I knew his “instrument,” his voice, so well.

We ran over it at Big Pink, and everybody thought, “Oh, yeah, that’s pretty good.” When we got into the studio, I really conveyed to everybody the way that I heard how the voices should work in this song. And it came so natural to everybody. Yet the timing of it is funny — the precision of landing in just the nick of time after those staggering voices, all of that. And even on the chorus — the voices aren’t tight.

Mettler: There is a microsecond delay there as they stack it — but it comes across as being real, and it really makes you feel like you’re there while it’s happening.

Robertson: Right — it is real, and it sounds like it. I didn’t want that smooth thing where everything is so tight that you can’t tell one voice from another. I didn’t want that. I wanted character. I wanted a story. And a story isn’t told by perfection. You need those things that are just slightly off that are so human, and so moving.

Mettler: Right at the very beginning of “The Weight,” I hear somebody, and maybe it’s John Simon, say something like, “It’s Take 13, and here we go” in the center, and then we hear, “Right right right” in the right channel. Is that you saying “right right right” before it kicks into gear?

Robertson: Yeah! When we started recording it, we were figuring out a couple of things as we were going along. But the engineers were like, “Wait a minute — we’ve got a problem here with this mic,” and we would do it again, but then it would be a false start. Then we would try something else, and they [the engineers] would say, “Oh no no no, I think we need to change the limiter on this.” It was all a bunch of technical stuff and false starts.

Finally, we’re getting to where we could play the damn song, and then they come on and say, “Okay, Take 13!” and I’m thinking, “We haven’t even played it yet,” you know? So that’s why I’m saying ,“Right right right.” Like, “It’s now Take 95 because of you guys — not because of us!” (both laugh)

Mettler: And then the song begins, and it sounds like an old 78. I’m not sure if it’s because of tape hiss or something, but it sounds like it could have been recorded 50 years earlier, in a way. It has a timeless quotient to it.

Robertson: I know! I know. Yeah.

Mettler: At about 3 minutes and 30 seconds into it, the organ part there that Richard does comes across a little bit differently than I remember hearing on previous versions, right before the “Catch the cannonball” verse kicks in.

Robertson: WOW! Wow, that’s really, really keen listening on your part! I don’t know that anybody else has caught that. There was a technical problem on the volume of it, and Bob said, “I’m gonna have to work on this to try to get this to come out properly.” He was going to have to use some of his mixing magic to get it to the way that we wanted it — and he pulled it off! And you caught that. That’s pretty sharp on your part. That’s pretty good, Mike. (chuckles)

Mettler: Well, thank you. When you’ve listened to a song so many times over the years and then you hear something in it that makes it sound even better, that’s just magic in action — so mission accomplished. And obviously, we have to give you guys another nod for enveloping us with the 5.1 mix of “Chest Fever.” I also feel Rick [Danko’s] bass in the second half of the song has more impact here.

Robertson: It is one of those tracks that, sonically, if you dig in a little bit deeper, there’s something even cooler going on. That track sounds unlike anything that anybody had ever done before — or maybe since! It has this thing that’s somewhere between magical and accidental (chuckles) — but in the way that the gods are on your side, when you’re doing it.

And we wanted that low end of the thing to serve its purpose. That was something that we couldn’t get back then because of the limitations of what you could get on a disk — you know, on vinyl. Sometimes, the mastering guy would say, “I’m going to have to cut a little of the bottom off of this, or the record’s going to skip.” We didn’t have those limitations [with the Blu-ray], so Bob was just able to push the button on that one.

Mettler: Since I actually have a bust of Johann Sebastian Bach in my living room, I gave it a bit of a nod as I was listening to Garth Hudson’s intro to “Chest Fever,” which has its own nod to Bach’s “Toccata and Fugue in D minor” in it. Garth’s infamous “black box” Leslie-like speaker and his Lowrey organ make that whole song about as unique as it gets. [Garth Hudson’s self-engineered “black box speaker” was essentially a mini Leslie speaker he built as a 2½-foot square box with sound vents on four sides of it, and it also had a fan inside that made the sound coming out of it that seemed to “whirl” around” as a “lo-fi raunchy swirl effect,” as Robertson describes it in Testimony.]

Robertson: Nobody played a Lowrey organ — nobody! Everybody played mostly the same kinds of organs then. And Garth, with his organs and his keyboards over the years, has always been so unique in his taste, and in the way he would hear things, and the way he would hot-rod the instruments.

Everything about Garth was original, and there has never been, in the story of rock & roll, a more unique organ player and keyboard player, ever.

Mettler: I agree — and this song alone defines its own sound. All throughout the album, I get this great sense of envelopment, and the way some of the fills come in around you. And like you said, with the physical limitations of vinyl in those days, you just couldn’t maximize what you, the artist, wanted us to hear. With all that in mind, will this release help get you and Bob to put your heads together to do a 5.1 mix of the self-titled album, The Band? Can we get a surround mix of that one, maybe next year for its own 50th anniversary? [The Band was originally released on September 22, 1969.]

Robertson: Well, that’s not a bad idea! I’m sure the record company is going to be thinking about that. Because that record wasn’t recorded in the studio, it was a different extension of the basement. [After some false starts in New York, The Band set up shop in the pool house of a rented home in the Hollywood Hills in California owned at the time by Sammy Davis Jr., in order to give The Band album a “clubhouse feel,” according to Robertson.]

At that time, I remember telling the people at the record company that we wanted to do that, and they didn’t even know how to respond. They just had these blank looks on their faces, like (slight pause), “WHY?? What’s wrong with you? If that’s what you really want to do, we’ll try to go along with it, but we kind of think it’s ridiculous.”

I was always impressed with the idea of recording in musical sanctuaries. Les Paul had his own world of recording, and nothing sounded like that. So, we’ll see. We’ll see. I think we’ll cross that when we get there. But I do wanna hear “Rag Mama Rag” in 5.1 myself.

Mettler: Yeah, we have to have that! “Up on Cripple Creek,” “The Unfaithful Servant,” and “King Harvest” are all just rife for being put into a good surround envelopment. See, now you’ve got plenty of work to do! (chuckles)

Robertson: I know! Geez! You’re not letting me get any rest.

Mettler: Well, you can rest “across the great divide,” as a certain song title of yours puts it.

Robertson: There you go! There you go. (chuckles)