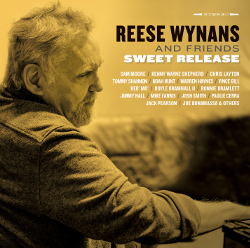

Reese Wynans: A Consummate Sideman Fronts His First, Sweet Solo Release

After the phrase “with a little help from my friends” entered the lexicon by way of those eternally fab pop innovators The Beatles, many sidemen and sidewomen have proudly worn that mantle when the way they selflessly support artists whose names are much further above their own on the big marquee gets described.

One name that’s long adorned such a favored friends list would be that of Reese Wynans, best known for his late-’80s stint adding much keyboard and organ flavor to the hardcore blues of Stevie Ray Vaughan and Double Trouble. Besides SRV&DT, the man has also contributed many a fine piano-born textures to the recorded works and live stages of artists including Buddy Guy, John Mayall, Los Lonely Boys, and Martina McBride. Most recently, Wynans has been tinkling the ivories in various band configurations for guitar prodigy Joe Bonamassa since early 2015.

But now, Wynans has finally stepped to the front of the queue alongside a slew of friends of his own to put forth his first-ever solo album, Sweet Release (J&R Adventures). “I know, man, what’s up with that?” Wynans says with a chuckle after I point out that it only took him over 50 years in the business to get there — even if he still felt compelled to add “And Friends” after his name in the title. “Well, I hope that it’s an album that’s accepted widely,” he continues. “I had a great time making it. It’s really an exciting time for me, just to have something out there with my own name on it.”

Indeed, Sweet Release teems with a veritable patchwork of indelibly great teamwork in action, from the Double Trouble rhythm-section revisitation of a trio of SRV classics — “Crossfire,” “Say What!,” and “Riviera Paradise” — to the stripped-back two-man duende Wynans shares with Keb’ Mo’ on Tampa Red’s “I’ve Got a Right to Be Blue” to the cavalcade of vocal talent trading off on the Boz Scaggs-penned title track (including the likes of Jimmy Hall, Bonnie Bramlett, Vince Gill, and Warren Haynes).

Wynans, 71, called in from his homebase in Nashville to discuss how he and producer/partner Joe Bonamassa decided where his organ should appear in the final mixes, why he began listening to vinyl again, and how he had to instantly be on his A-game when he first joined up with Stevie Ray Vaughan and Double Trouble. We got stranded, caught in the crossfire. . .

Mike Mettler: When you were mixing this record, did you feel you needed to bring yourself more front and center because your name is at the top of the marquee here, as opposed to being more in the background of a mix when you’re a sideman? What was your goal in terms of how you wanted to hear yourself come across in the final mixes?

Mike Mettler: When you were mixing this record, did you feel you needed to bring yourself more front and center because your name is at the top of the marquee here, as opposed to being more in the background of a mix when you’re a sideman? What was your goal in terms of how you wanted to hear yourself come across in the final mixes?

Reese Wynans: Well, Joe Bonamassa, my producer and the guitar player who I play with now, and I kinda disagreed on this. I felt that, on each individual song, you had to determine where the keyboards, the guitars, and each individual instrument were going to align in the mix. Joe said, “Nah — since it’s your record, I think you gotta be front and center all of the time. People wanna hear what you’re playing on it.”

So, we kinda compromised. Usually, the organ is front and center most of the time like he wanted it to be, but occasionally, it’s backed up a little bit more to where I thought it would be a little more realistic. (chuckles) But, you know, I don’t really have that much experience putting a Hammond B3 or any other organ on a record that has my name on it, because I never had a record with my own name on it before.

Mettler: Well, better late than never, I say. Let’s get into your background. You grew up in Florida, right?

Wynans: Yes, I grew up in Sarasota and Clearwater. I also played in northern Florida — in Jacksonville, which is where I hooked up with [guitarist] Dickey Betts, [bassist] Berry Oakley, and [guitarist] Duane Allman back in the day.

Mettler: That’s right, you were almost the “third Allman Brother,” so to speak.

Wynans: I could have been, way back when! You know, at the same time we were all getting together and jamming in Jacksonville, Tom Petty and The Heartbreakers were getting together in Gainesville, about 200 miles to the south. I’m a big fan of theirs, and I love their keyboard player, Ben — Benmont Tench. I just love the way he plays. There was a whole lot of musical talent down there in Florida at that time.

Mettler: Yeah, that’s true, because you also had Don Felder and Stephen Stills down there too, who also crossed over into that universe. Everyone around the area seemed to share in a similar mentality at that time.

Wynans: Exactly — bands like Marshall Tucker, Lynyrd Skynyrd, and all that Southern rock that was just getting started back then. We were a part of that, when I was in The Second Coming with Dickey [Betts] and [drummer/percussionist] Jaimoe [from November 1968 to March 1969]. We would take all these songs and stretch ’em out and jam on ’em. Sometimes we’d take ’em real slow and get a real greasy, funky groove on them. It was a blast to do them, and it was where that whole Southern rock thing kinda started. That was the cradle of all that, I think. [Wynans also jammed with an early incarnation of The Allman Brothers Band before Duane Allman decided he only wanted one keyboard player in the group — his brother, Gregg Allman.]

Mettler: Speaking of flavor, one of my other favorite tracks on Sweet Release is one you did with Keb’ Mo’, “I’ve Got a Right to Be Blue,” which has that old, 45, Robert Johnson-sitting-in-the-corner kind of feel to it.

Wynans: We did two songs by Tampa Red, who was a guy I listened to a lot. When you talk about the people who are sort of the unknown blues masters who came up with some terrific songs, I think Tampa Red was one of those guys. I wanted to do a couple of his songs [the other one was “So Much Trouble”], and I thought Keb’ Mo’ was the perfect choice to do “I’ve Got a Right to Be Blue.”

And yeah, we wanted it to sound like an old, vintage record — just the two of us playing. Joe came up with the idea of us sampling the sound of an old, dirty phonograph needle on a record with that kind of scratchy sound. And it’s just Keb’ Mo’ and I, playing that song together. Then we took the whole track and ran it through an old Fender tweed amplifier, which is how we got that vintage-y sound.

Mettler: Did you put on an actual Tampa Red record to get that scratchy sound? (chuckles)

Wynans: I don’t know where they got it from, but that would have been a great story if they did get it from Tampa Red, yeah!

Mettler: I also like the vocal response at the end that you kept in there: “Yeah, that felt good!” Was that Keb’ Mo’s reaction in the moment, right after the take?

Wynans: That was actually my reaction.

Mettler: That was you? Okay, well, you were right, because it did feel good! And since we’re talking about vinyl, I’m glad we’re also getting Sweet Release on vinyl too. It’s a requirement at this point, I think.

Wynans: That is absolutely a requirement. I just started listening to vinyl again. I bought a turntable about a year ago, and vinyl just sounds so much better to me than listening to songs off the computer, or even on a CD player. There’s more data that you can hear and there’s a warmth to it that I’ve missed, so it’s great to hear songs again on vinyl — and now you’ll be able to hear my songs on vinyl too.

Mettler: What kind of turntable did you get? Do you know the name of the brand offhand?

Wynans: Well, I can go and take a look for you right now. I have to tell you that I thought I was going to get a really nice, beautiful, $10,000 or $20,000 type hi-fi, and a friend of mine reminded me, “Reese, just find something that Sam & Dave sounds good on, and you’ll be happy.” So, I went and got a whole system for about $1,200.

Let’s see. I’ve got a Sony turntable, a Yamaha receiver, and a couple space-age speakers that stand up on the floor, and they just sound great.

What am I listening to? I’ve got a couple of Hans Zimmer movie soundtracks, some Dave Matthews Band vinyl, and some Jimmy Smith and Oscar Peterson — a little bit of this, and a little bit of that. It’s a beautiful thing, to be able to listen to music that just washes over you.

Mettler: I can totally relate to that. What was the first record you got that had major impact on you, something you bought as a kid that still sticks with you?

Wynans: Well, I did have a little hi-fi, and we bought 45s when I was a kid. I liked this piano player, Jerry Lee Lewis. I bought a couple of his records. And I liked this guitar player, Chuck Berry, who had this great piano player, Johnnie Johnson. Even back then, the tinkly piano, set off the guitar — and that was an education in the way that happened, showing how somebody could play in a rock & roll band.

Mettler: Did you gravitate toward piano immediately as a kid? Was that the first thing that connected with you as an instrument?

Wynans: Yeah, yeah. My one grandfather played piano in church, and my father played piano and organ, just for his own enjoyment. We didn’t have any professional musicians in the family but we always had a piano in the house, so I guess it was a natural thing for me to gravitate toward that.

Mettler: Was there a composition you remember playing first, or did you take lessons?

Wynans: Well, we all start out playing out of those ridiculous books — the nursery-rhyme books and the single-note melodies that you work out — but I was good at it. I just stayed with it. We all took piano lessons in my family, but I stuck with it for 10 years, and I enjoyed it.

I had this sense of making music and I realized I had this creative spark in me that just fulfilled something, and I just loved playing the piano and making music. I’ve always done that, but I never thought I’d make a living being a piano player. I thought I’d be a music teacher, or something like that. But you have to have a LOT of patience to be a teacher — and I don’t think I have that much patience. I complain too much! (chuckles)

Mettler: Well, we like seeing you up onstage. I’m sure you’ve heard a lot of stories like this, but I first saw you play with Stevie Ray Vaughan and Double Trouble in December 1985 at a small bar called Easy Street in Des Moines, Iowa. I was going to college there, and I was underage and borrowed a friend’s ID to go to that show. Couldn’t have been more than 100 people in that room, and you guys played for over three hours. It was one of those top-five-shows-ever kind of nights.

Wynans: Wow. Well, I was just new in the band then, and it was kind of different than what I expected it to be. I thought that, when I joined Stevie Ray Vaughan and Double Trouble, I would just play on the songs that I was on, on the record [Soul to Soul] — not all of them, but just some of them — and then they would just continue on as a trio. [Wynans started recording with SRV&DT circa April 1985, not long after the recording session for the band’s aforementioned September 1985 release Soul to Soul commenced.]

But, no — Stevie wanted me to play in the whole show; he wasn’t having any of that nonsense! “You’re playing the whole show!” (chuckles) The first show, I remember clear as day. There were about 10,000 people in Dallas [at the Dallas Convention Center on April 21, 1985]. Before that, I had never played any of those songs, except for the ones on the record. Then, about a month or so later, we were in Chicago at the Chicago Blues Festival, with 75,000 people [at the Petrillo Music Shell in Grant Park on June 7, 1985]. Right into the fire there, you know? I just had to be ready for all these shows. Then, a month later, we flew to Europe to play the Montreaux Jazz Festival [on July 15, 1985 in Montreaux, Switzerland].

Mettler: To borrow a line from the song that starts your album, you were literally standing in the crossfire.

Wynans: (laughs heartily) I love it, man — that’s exactly right! It’s like anything else — when a door gets opened like that and opportunity comes, you walk through the door, but you have to bring something to make it work. You have to bring your talent with you. I tell you, I loved playing with Stevie Ray Vaughan and Double Trouble. I loved that music, and they were a great bunch of guys. And it was really a thrill getting to record some of our old songs for this new record.

Mettler: I love that “Say What!” is in the second position on Sweet Release, because it used to be the second song you’d play in the set in those days whenever it wasn’t the set opener. It’s an organic entry for having you join into the mix of that band’s sound. You filled in with a feel that made it sound like you’d been there all along. Was it an instinctual thing for you, being able to blend in as part of an ensemble like that?

Wynans: Well, I’ll tell ya — I could have played a lot more than I did on that stuff. But I thought that they were a fantastic trio, so I didn’t want to change ’em, you know? I thought I would just try to add to it and make it bigger, and give it a fatter sound altogether.

And on that particular song, “Say What!” — we got the idea for that groove from a Jimi Hendrix song, “Rainy Day Dream Away” [the first track on Side 3 of October 1968’s Electric Ladyland]. When I was talking to [Double Trouble drummer] Chris Layton about that song, he wanted to play it again, and [guitarist] Kenny Wayne Shepherd wanted to play that one too.

Mettler: It’s the perfect blend of generations right there. On the original track, when you guys all shout out “soul to soul,” is that just an improv shout-out in the moment, or did Stevie come up with it?

Wynans: I don’t know who came up with saying that, but we cut that the very first night I was with the band. I wasn’t going to ask any questions about that. “Everybody get over here and sing, ‘soul to soul’!” “Okay! I’m there!” (chuckles)

Mettler: I’m also glad you have your version of “Riviera Paradise” on this album. That was the first thing I put on when I learned that Stevie had passed away [on August 27, 1990]. And as I understand from [Double Trouble bassist] Tommy Shannon, who I talked to about it a few years ago, that was done in just one take, right?

Wynans: It was done in only one take but the headphones were all out of whack, because we had just played something loud and raucous before that. The headphones were set for a “loud” song. And Stevie said, “Let’s do ‘Riviera Paradise’ now. Turn the lights down a little bit, and go.” So he’s playing the intro, roll tape, and here we go! That’s the way that track worked out, and yes, we only played it once in the studio.

Mettler: Talk about a lightning in a bottle moment. On the intro to “Riviera Paradise” on your record, you take some of Stevie’s parts on the organ, and then we have that wonderful guitar tandem of Joe [Bonamassa] and Jack Pearson in there, playing their own thing. Again, this is just your instinct of how to pepper the right flavor at the right time. You’re like that special seasoning on everything.

Wynans: (chuckles heartily) I love that! The special seasoning! (laughs again) This particular song — it’s such a great song, and I always wondered why other people hadn’t played [i.e., covered] this song. Not many people play it, but to me, it’s a beautiful song. I think of it as a movie soundtrack kind of song, with a wistful melody. On this version, I wanted to bring the [Bova] Orchestra in to play the lush string parts on it, and I think it worked out beautifully.

Mettler: You could almost call it something like “Tales of an Imaginary Texas Western,” or something like that.

Wynans: Exactly, exactly — everybody can visualize whatever they wish. And that’s the wonderful thing about music — it’ll take you somewhere.

Mettler: I could go back out there in a heartbeat. In the album’s booklet/liners, there’s this great black-and-white photo of you with headphones on at an organ with some stained glass behind you. Where was that photo taken?

Wynans: I was cutting the record at Ocean Way [in Nashville], and that’s a room I played in a lot. I just love recording there. There’s plenty of room for us all to set up live around each other in the main room, which is what we did. When you go in there to listen, the control room is big enough for us all to hear well. And downstairs, they have a pool table, so what else do you need?

Mettler: Yeah, that’s perfect! And pretty much everything was cut live, with everybody in the same room together?

Wynans: Just about everybody. The basic tracks were cut live, and I did all the solos live. Joe was there, Kenny Wayne Shepherd was there, Jack Pearson, and [guitarist] Josh Smith was there. Mahalia Barnes did [background] vocals. We sent out some tracks — we sent out to Warren Haynes and Doyle [Bramhall II], who couldn’t make it to Nashville. We sent out to Sam Moore to sing [“Crossfire”], and Vince Gill to sing [a verse on “Sweet Release”]. But I think most everybody else was there.

Mettler: Do you feel you have a better connection while you’re looking somebody in the eye in the same room when you’re recording?

Wynans: Absolutely! No question about it, especially for the basic tracks. I don’t know how people can put down a piano track, and then a drum track, and a bass track, and then send it out to different places. I think you miss something in the communication when you’re doing that. I like sitting around in a room with a bunch of live people, looking at each other, listening to each other — that’s what I’ve always done, and that’s what I like doing.

Mettler: I’ve attended a number of recording sessions as a semi-partial observer, and you can tell there’s that unspoken intuitive language when people are looking at each other and can anticipate what that next note or fill is going to be, and you can only do that when you’re in that position. Now, I’m going to go out on a limb, Reese, and say you have a future in doing more solo albums. We won’t have to wait so long for you to do another one, right?

Wynans: I think because of the way this turned out so well that I would love to do another record. I’ll talk it over with Joe to see if he wants to produce it. I’m starting to get some new stuff together already, so you got a deal, Mike.