Keyboard Maestro Tony Banks Writes His Next Chapter

“That’s a lovely, fantastic thought, and I’m right there with you,” Banks says in response to the idea, with just a tinge of his patented dry sense of humor. “No one can argue with you, because in 100 years’ time, we won’t be there to see it. But, principally, I think my main contribution to everything I’ve done with Genesis and on my own has been as a writer. That’s my greatest attribute, and that’s what I want to be judged on, in a sense, rather than my keyboard playing.”

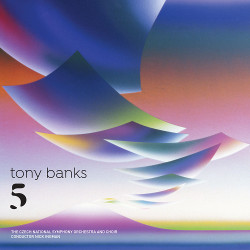

Fair enough. Post-Genesis, Banks has focused on his writing skills via a trilogy of classical-oriented releases: 2004’s Seven: A Suite for Orchestra (Naxos), 2012’s Six Pieces for Orchestra (Naxos), and his latest, 2018 effort, 5 (BMG). The five pieces on 5 essentially emerged from Banks having been commissioned by music director Meurig Bowen to write a 15-minute piece for a live orchestral performance at the Cheltenham Music Festival in Britain in July 2014. That composition, initially known as “Arpegg,” then evolved into the opening track on 5 now known as “Prelude to a Million Years,” which features orchestral arrangements by conductor Nick Ingram and is performed by The Czech National Symphony Orchestra and Choir.

I got on the line with Banks, 68, to discuss the evolution of his orchestral compositions, his ongoing appreciation for the surround sound mixes of the entire Genesis catalog and his solo material, and what he might (or might not) tackle next. The path is clear. . .

Mike Mettler: I’m curious how much you feel “Arpegg” evolved from its first performance at the Cheltenham Music Festival to how it appears now as “Prelude to a Million Years” on the 5 album.

Mike Mettler: I’m curious how much you feel “Arpegg” evolved from its first performance at the Cheltenham Music Festival to how it appears now as “Prelude to a Million Years” on the 5 album.

Tony Banks: With the basic composition, there’s actually very little difference, but the arrangement has changed somewhat. I went back to it and fiddled around with it a bit, and I worked with a new arranger, Nick Ingman, to help me finish it off.

It was interesting when I first heard back the live Cheltenham performance of “Arpegg,” which is short for “Arpeggio,” and was the working title. Part of it sounded lovely and then other parts didn’t sound too good, so I had to think, “How do I get it to sound right?” When you get the whole orchestra playing at the same time, you go, “Well, the flutes are great in there, but the brass is a bit loud,” so you try to fiddle around with it. And what I decided to do on this particular record was to deconstruct it and then record it in parts in the orchestra separately, so I’d have more control. We did it more like a rock album, where you add stuff in later, like the guitars.

We started off with my demos as the sort of template, and the only thing that really survives from the demo is the piano. We substituted my parts of everything else, or added other pieces to it. It’s how I wanted the whole record to go. It was an interesting way of working, since I could really control each aspect of it.

The other thing you can really control using this sort of template is the tempo of everything. You get all the rolling timbres, where all the speeds are absolutely right. What I found on the last two orchestral albums I did [the aforementioned Seven: A Suite for Orchestra and Six Pieces for Orchestra], while I was very happy with a lot of it, there were moments where the speeds were just wrong. And I never got at ease with that.

Mettler: I suppose there wasn’t anything you could do with the performances themselves at that point.

Banks: No. Once it’s there, it’s there. That’s the problem — once you’ve recorded the orchestra all together, what you’ve got is what you’ve got. Sometimes you get some surprises when they’re playing all together and it works better than you think it would, but other times you think, “Well, that’s not as good as it could have been.”

What I wanted was to do one of these orchestral albums where the results sounded like what I originally had in my head. And that’s what we’ve got here on 5. A large amount of the arrangements is what I originally put down. And obviously, Nick Ingman did a fantastic job of transcribing what I did, and then embellishing and adding in a lot of music, especially in the percussion area. If you heard the demos and then you heard these finished mixes, you’d find there’s a certain bit of resemblance. And this time, whether you love it or hate it, is just what I intended. (chuckles) In the past, I’ve done things where I go, “That’s not what I really meant,” you know?

Mettler: I get it. You want 5 to best represent your original idea for how it should sound. Ultimately, it’s your name that’s out there, and on the front of it.

Banks: It is. And principally, I’m a writer. That’s what I want to be judged on, in a sense, rather than my keyboard playing. And although I do play piano on this material, it’s never significant. It’s never upfront.

Mettler: Right — it’s kind of kept back in the overall mix.

Banks: That’s right.

Mettler: There are a number of volume swells that appear during the back half of “Prelude to a Million Years.” Is that something you and the other Nick, [longtime Genesis/Banks producer/engineer] Nick Davis, have to work out in the mix, in terms of where you want things to be accented like that?

Banks: You get everybody to do as much as they can. Like the choirs and the strings, they will do it. And I suppose when you get to the mix, you work on it a bit to get it absolutely the way you want it, but these things do happen in orchestral music where you get these kinds of swells.

I’ve always liked these kinds of crescendos. There’s a piece I did many years ago which is actually the opening piece from my first solo album [October 1979’s] A Curious Feeling called “From the Undertow,” which is all really built on swells — and that was what it was all about, where these chords would come in. I think it’s just such a strong thing, but it’s something that’s not used that much in rock music — though obviously Genesis did it back in the day.

Mettler: The end of [The Beatles’] “A Day in the Life” is another obvious example of that.

Banks: Yes. But modern pop music tends to be very static in terms of the dynamic, where it needs to come in at a certain point to do its thing.

Mettler: We need more of that “The Cinema Show”/“Supper’s Ready” kind of approach.

Banks: Well, I love things that go up and down all the time. It’s not to everybody’s taste, but it’s what I do and what I like, and there are people out there who do like this sort of thing. I like pieces of music that go through various changes, and three or four of the pieces on this record do go through quite a few changes. Each one takes you on a sort of journey — an emotional journey, if you like — but you’ve got to stick with it.

The problem is, I’m a bit old-fashioned, I suppose, looking for people to listen to longer pieces for a few minutes when they only have a 10-second attention span. I’ve got a problem, I know that.

Mettler: Luckily, you’re speaking with someone who has a similar problem — someone who likes sitting down to listen to 50 minutes of music uninterrupted. And I’m glad you mentioned “From the Undertow,” because when we talked about A Chord Too Far in 2015, we discussed the surround sound mixes you and Nick Davis did for both that album, and [June 1983’s] The Fugitive. Naturally, I think 5 needs to have a subsequent release called 5.1, wouldn’t you agree?

Banks: (laughs) Oh, yeah! Funnily enough, we never did a 5.1 for it. We did do a 5.1 for the first of these, Seven, so there is a 5.1 of that one in existence [albeit still unreleased, as of this posting]. And we could quite easily do a 5.1 mix of 5. We could release a Blu-ray version of it, though I’m not sure how popular it would be. It’s sort of gone the way of quad, which I thought always had a nice sound.

Mettler: The Esoteric Recordings label, which you’ve released albums on internationally, has been very supportive of the 5.1 format with many of its artists, and Steven Wilson continues to put out his own solo material in 5.1 on Blu-ray himself, so there is a certain kind of audience willing to buy it and listen to it. Given the platform, would you be interested in doing a 5.1 of 5 to put us in the literal middle of the orchestra while we’re listening to it? It seems to be a natural fit.

Banks: I haven’t thought too much about it, but knowing record companies these days, if they can release something ten different times and can sell it, they’ll do it. (both laugh) But it’s something that would be very easy for us to do, particularly because of the way we recorded it, doing all the things separately. You can certainly imagine it in 5.1. You want to make it sound like an orchestra, and the orchestra is very much in position because they are separate. They are very separate.

We didn’t do it this time around since that wasn’t where our heads were at with it, but we did do it with [July 2015’s] A Chord Too Far. A lot of those pieces exist that way. Speaking as a writer, it’s a great thing to do. I love the sound of 5.1. When we redid all the Genesis albums in 5.1, obviously, we got very experimental on [November 1974’s] The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway with the stuff out of the back and everything, which was great.

I think 5.1 is a wonderful thing. Even the ones that we did quite “straight,” like the opening to “The Cinema Show,” and everything there in all the different places — I thought it was quite magical. For me, that’s my favorite moment of all the Genesis 5.1s — the first half of “The Cinema Show,” and the way it glides, and all that. Quite extraordinary.

Mettler: I often put on the extended piano opening you do on “Firth of Fifth” that’s in 5.1 on the Blu-ray version of [October 1973’s] Selling England by the Pound. I audition my surround system for people with it along with “The Cinema Show,” which is also on that album.

Banks: That’s really nice that you do that! And you’re right in a way, because I suppose one could argue that the only way you’re really going to hear it in full and in the moment is when you buy the Blu-ray. Spotify or YouTube isn’t going to give it to you that way. It’s an interesting thought, really.

Mettler: I also have to say I think “An Island in the Darkness,” the Strictly Inc. track you did with Wang Chung’s Jack Hues that also features some absolutely amazing guitar work from Daryl Stuermer, would be a great track to hear in 5.1. It’s got such a majestic scope to it that’s perfect for surround sound, I think.

Banks: I wouldn’t have any objection to that. And yes, it was on my Strictly Inc. album [released in September 1995], which unfortunately sank without a trace. It’s one of the best things I ever wrote, and I’m very proud of it. It’s also another one of those tracks that’s 15 minutes long. The longer they are, the better they are, in my opinion. Who knows? I’d like to do 5.1s of everything, but it’s just a matter of finding the time and getting them out there.

The main problem you have with projects like these is just to let everyone know it’s out there. There’s so much stuff out there and there are no obvious radio stations, and few people play this kind of music. It’s either pop music, classical music, or talk stuff. Some things like this that are in between are somewhat difficult. But I’ve done all I can do, really. (chuckles) Hopefully, I’ve done the best record I can do, and I can only hope you’ll like it, and that we’ll get picked up on.

Mettler: We’re doing our part to help with that. The intro at the beginning of “Reveille” really has a kind of “signature” Tony Banks feel to it, doesn’t it?

Banks: I’ve always used this sort of technique where the two hands cross each other so I can play in the same area. I’ve used it at the most effective level and most prominently on the opening of “The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway” — the opening, and the rest of the song. It’s the same technique used there. It’s a way of playing soft and rhythmically in a way that (slight pause), well, that’s actually not too difficult to do! (laughs) It’s one of the reasons for doing it, and I love the way it gives a stronger momentum to a piece.

Mettler: We’ll have to find you and Nick Davis the time to make that all happen, then. Is it too early to say what you’re doing next? Since you have Seven, Six Pieces for Orchestra, and now 5, will the next one you do go one more back and be called 4?

Banks: (laughs) Well, there you go! I hadn’t intended this one to be called 5, but we wound up with five pieces, so I couldn’t see a way around it. But I really haven’t written anything since that, which is quite a few months ago. So, I don’t know. Maybe I’ll just sit down at the piano and see what happens.