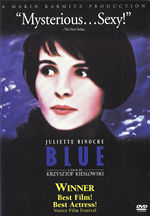

Three Colors

Juliette Binoche, Benoît Régent, Charlotte Véry. 98 minutes. 1993.

White (Blanc)

Zbigniew Zamachowski, Julie Delpy, Janusz Gajos. 92 minutes. 1994.

Red (Rouge)

Irène Jacob, Jean-Louis Trintignant, Jean-Pierre Lorit. 99 minutes. 1994.

All three: Directed by Krzysztof Kieslowski. Aspect ratio: 1.85:1 (widescreen). Dolby Digital Surround (French with English subtitles). Miramax Home Entertainment 47539. R. $39.99 (films not available separately).

When Polish writer-director Krzysztof Kieslowski and his co-writer, Krzysztof Piesiewicz, came up with the idea of making a cinematic trilogy that would be a tribute to the ideals expressed by the French tricolor—liberty, equality, fraternity—they were adamant about exploring each of these in a contemporary, nonpolitical manner. Instead, the three films of Three Colors delve into the mind, focusing on emotions visible and hidden, and on ideals and principles that confront us with a sense of urgency that does not quit: How close can we get to others? How powerful are our memories? What impact can death have on the living?

In Blue, the most powerful of the three, a woman (Juliette Binoche) is so traumatized after surviving a tragic accident that claims the lives of her composer husband and her daughter that she withdraws from life and tries to detach herself from anything that can cause pain, including relationships, objects, even art. But even as she does her best to savor small pleasures that make no demands on her heart—a cup of coffee, a swim in the pool, the life around her—her pain won't go away. She starts to live again only when she becomes interested in and shows compassion for the people near her—a hobo in the street, a stripper neighbor in trouble, and, especially, her late husband's assistant, who loves her and wants to finish the symphony the dead man had begun.

In Blue, the most powerful of the three, a woman (Juliette Binoche) is so traumatized after surviving a tragic accident that claims the lives of her composer husband and her daughter that she withdraws from life and tries to detach herself from anything that can cause pain, including relationships, objects, even art. But even as she does her best to savor small pleasures that make no demands on her heart—a cup of coffee, a swim in the pool, the life around her—her pain won't go away. She starts to live again only when she becomes interested in and shows compassion for the people near her—a hobo in the street, a stripper neighbor in trouble, and, especially, her late husband's assistant, who loves her and wants to finish the symphony the dead man had begun.

Blue is the color of liberty, and Blue examines the freedom or lack of freedom from feelings and commitments, as well as the freedom to belong or to reject the world around us. Binoche gives a heartfelt performance as the tormented heroine who tries to keep her suffering private. Benoît Régent is the man who patiently waits for her to respond to his affections.

By contrast, White is a darkly comic glimpse into the mind of Karol Karol, a nebbish Polish émigré in Paris who loves his doll-faced wife to death. When she divorces him and throws him penniless into the street, Karol returns to Poland, desperate and devoid of any self-esteem. But he regains control of his life and comes up with a devilish plan to get his wife back and punish her for good.

White (the color of equality) is the most plot-driven of Kieslowski's trilogy. The hero (Zbigniew Zamachowski) strives to assert his manhood, and to gain empowerment to "wrestle" with his ex-wife (Julie Delpy). But intricate plotting is not the filmmaker's strength, and some elements here are simply over the top: the hero sends himself as luggage on a plane and survives; he frames his wife for his own clumsily faked murder and gets away with it. Another logical flaw is that the protagonist gets revenge but not equality, because he can't stop loving his wife even after he's landed her in jail. But this may be quibbling about an oeuvre that explores states of mind. Zamachowski conveys comic desperation, Slavic style, to perfection.

Red (fraternity) is about a young model (Irène Jacob) who befriends an older man, a retired judge (Jean-Louis Trintignant), after she runs over his dog with her car. At first repelled by the man's manifest cruelty, his death wish, and how he spies electronically on his neighbors, she slowly comes to understand the tragedy that has propelled him to live his life vicariously. The two connect, but the difference in their ages precludes romance. Meanwhile, a young man (Jean-Pierre Lorit) whose life parallels the judge's is being steered by life's many coincidences—a favorite Kieslowski subject—in the heroine's direction.

Red (fraternity) is about a young model (Irène Jacob) who befriends an older man, a retired judge (Jean-Louis Trintignant), after she runs over his dog with her car. At first repelled by the man's manifest cruelty, his death wish, and how he spies electronically on his neighbors, she slowly comes to understand the tragedy that has propelled him to live his life vicariously. The two connect, but the difference in their ages precludes romance. Meanwhile, a young man (Jean-Pierre Lorit) whose life parallels the judge's is being steered by life's many coincidences—a favorite Kieslowski subject—in the heroine's direction.

Jacob, who starred in Kieslowski's intriguing The Double Life of Veronique, shines as a woman who gets in touch with her most unexpected emotions, and veteran actor Trintignant lends a sympathetic human face to the twisted character of the judge. Red proposes that true friendship is possible between people who seem to be poles apart, and that such friendship can fire their quest for freedom and help them achieve a deeper equality that a romantic involvement would make impossible.

Viewed in sequence, these three works of art, unusual in their cinematic syntax, visual clues, and strong belief in coincidence and destiny, invite us to meditate on what makes us tick, and what we make of the people and reality we are dealt. Larger than the sum of its parts, the trilogy veers between overt pessimism (Blue) and guarded optimism (Red), navigated by Kieslowski's haunting lyricism. The complexities of the human soul are explored by moody musical scores (all three by Zbigniew Preisner) that echo or contrast with a character's mood. The masterful editing weaves a visual feast of layered transitions that are as solemn as they are surprising; bold silences abound, as do fadeouts that divide scenes in two with pregnant pauses. And Kieslowski's camera glides elegantly along external surfaces just as expertly as it pauses on a protagonist's face. These long journeys into the night of the soul are painful, truth-seeking explorations that never fail to reward the viewer.

Viewed in sequence, these three works of art, unusual in their cinematic syntax, visual clues, and strong belief in coincidence and destiny, invite us to meditate on what makes us tick, and what we make of the people and reality we are dealt. Larger than the sum of its parts, the trilogy veers between overt pessimism (Blue) and guarded optimism (Red), navigated by Kieslowski's haunting lyricism. The complexities of the human soul are explored by moody musical scores (all three by Zbigniew Preisner) that echo or contrast with a character's mood. The masterful editing weaves a visual feast of layered transitions that are as solemn as they are surprising; bold silences abound, as do fadeouts that divide scenes in two with pregnant pauses. And Kieslowski's camera glides elegantly along external surfaces just as expertly as it pauses on a protagonist's face. These long journeys into the night of the soul are painful, truth-seeking explorations that never fail to reward the viewer.

Miramax home Entertainment has done wonders. The transfers are luminous, with crystal-clear images and vibrant colors. The Dolby Digital Surround sound is excellent, and the yellow English subtitles are accurate and readable.

This boxed set is full of bonus materials: featurettes about Kieslowski, who died in 1996, and his filmmaking technique; interviews with his close collaborators, including the leading ladies of Three Colors; and several of the director's short student films. A must for every serious lover of film. —DY

- Log in or register to post comments