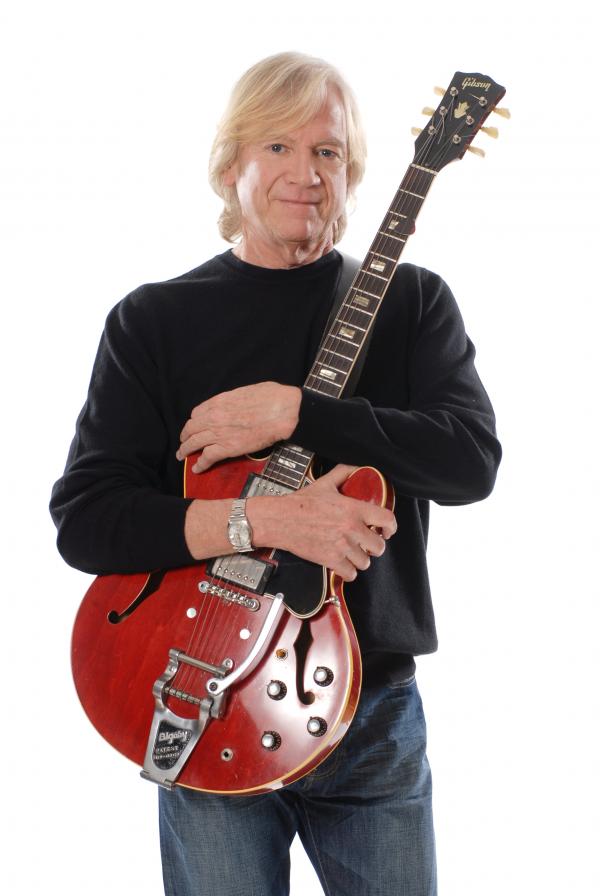

Days of SQ Surpassed: Justin Hayward of The Moody Blues

After recently speaking with former Moodies keyboardist Mike Pinder about the band’s surround-sound proclivities, it seemed only natural to check in with their chief songwriter and lead singer to get his take on how the sound-quality threshold has changed over the years. Here, Hayward, 67, and I discuss the birth of FM, his favorite recordings, and his top Moodies-in-5.1 moments. Timeless indeed.

Mike Mettler: As an artist first recording in the ’60s, how did you feel about the transition from mono to stereo?

Justin Hayward: Well, I didn’t even have a stereo unit until around the time of A Question of Balance [1970]. I couldn’t afford one, and I didn’t have space in my little apartment. I was stuck with my Dansette record player. It was when I came to America with The Moodies that I understood how important a good stereo spread was. With the birth of FM radio, all those disc jockeys were crying out for stuff mixed like ours was, instead of stereo recordings with the drums mixed on the right and vocals on the left. And then, of course, you can’t go back. But that didn’t stop me from loving what I had, my old Dansette, and appreciating the mastering of those old singles.

Mettler: The Moody Blues really helped define the scope and reach of FM radio here in the States. Do you remember hearing one of your songs on the radio in America and getting a sense of what other people were hearing and connecting with?

Hayward: Absolutely. It was a great opportunity for us. We didn’t have FM in the U.K. for so long, but the Americans were well into it. And once the walls had come down, they were totally into it. Of course you still had AM stations, which were still great. But with that little bit of compression, it always sounded pretty good to me on an FM station.

Mettler: Let’s talk about surround sound. Is there one song or album in the catalog that you would cite as the best example of the full-on 5.1 experience?

Hayward: Yeah, that’s a tough one. I didn’t have the courage to go back to any of the masters and try to recreate those beautiful, real echoes. But it’s still Days of Future Passed that hit it the most. All of the time we were mastering it, I was thinking, “How the hell did we do that?” There’s a song on there called “Dawn Is a Feeling,” where Mike [Pinder] got the mellotron just right.

Mettler: Working with production people like [producer] Tony Clarke and [engineer] Derek Varnals certainly helped get the best out of your sound.

Hayward: Oh, they were really superb. Derek Varnals — I have to credit him with my guitar sound in the early days. On those early records, I played acoustic and electric. He captured all of that just beautifully. I’d put the acoustic lines down first, and then we’d do the electric stuff, maybe with the other guys playing at the same time.

Mettler: Are there a few particular examples of Derek capturing just what you were looking for?

Hayward: There’s a song called “It’s Up to You” [on A Question of Balance], where he suddenly nailed it down, and “The Story in Your Eyes” [on Every Good Boy Deserves Favour], which has some exceptional guitar sounds. I was playing them flat-out. He wanted me to play standing in front of the amplifier, a Vox AC30, turn the normal channel up full, and blast it out. That was the sound.

Mettler: And by the time you get to recording a song like “Question,” Tony and Derek have clearly mastered how to capture your acoustic guitar sound on tape.

Hayward: We owe them both a great debt. I still see Derek occasionally. He hasn’t changed.

Mettler: I spoke with Derek for a good 2 hours or so last year, and he was quite generous in sharing the minutiae of recording at Threshold Studios and what he did for the quad mixes; all of those little details. For him to be able to capture and share the full effect of what you poured your heart and soul into recording is just fantastic.

Hayward: I think the quality of engineering went backwards after that. In the ’60s, you had these well-trained engineers, but when people started doing their own things in their own studios — “Ah, I think I can do this!” — they didn’t have the same kind of training. It came down to the stuff being done in the U.S. by the Eagles and Jackson Browne to really bring that quality of recording back again.

Mettler: Good point. In those days, the engineers were doing essentially an apprenticeship with the producers, doing everything hands-on in the studio, learning all the ins and outs. Guys like Glyn Johns —

Hayward: Right. And producer Tony Visconti, who worked with us on “Your Wildest Dreams” [for 1986's The Other Side of Life], was an engineer. There was no other engineer in the studio.

Mettler: Besides the Eagles and Jackson Browne, what other artists made records that sound great to your ear?

Hayward: Well, of course, the kings of that were Steely Dan. Most people would say that. Their stuff was mastered so beautifully, mastered tastefully and not too loud, with the full frequency range. I think the things that were happening in California, a process started by Buffalo Springfield and then Poco, was a really tasteful kind of business.

Mettler: There’s a certain sonic quality we’ve come to expect from a Moody Blues show, which must be foremost in your mind — how that comes across, how the music is presented.

Hayward: It absolutely is. There are great limitations on the building itself — whether it’s conducive to a sweetness of sound, and that’s sometimes frustrating. But I’m a great believer in less is more. I was part of a benefit in San Francisco a few weeks ago for the late Ray Dolby, and it was Jack Vad, the engineer for the San Francisco Symphony, who did the front of house. He was just sensational. When I met him before the show, I said, “I’d like it to be quiet.” And he said, “Oh, I’m so glad you said that.” [laughs] So, yeah, less is more for me, I think.

Mettler: How wonderful Ray Dolby was as an innovator.

Hayward: Oh yes! I didn’t know this until Dagmar Dolby, his wife, shared this with me, but the first Dolby system was put in Decca Studios in West Hempstead [in England], and we were the first group to use it. The only thing I remember from those days was that we had to fill in these forms, and then they’d wheel these big racks into the studio, and you could only have them for a certain time, and then they’d come back and wheel them out again. It changed things forever, and I was very pleased to be a part of that.

And that’s why they’d asked me to be there. I’d just assumed that since he was an American, the system was first used in America, but it wasn’t. She also told me that Decca tried to keep it for themselves. Once it was out of the box, it was impossible to hang onto.

An extended version of this interview appears on Mike Mettler’s own site, soundbard.com.