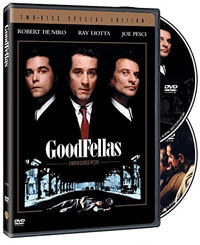

Cinessentials: GoodFellas

Ray Liotta, Robert De Niro, Joe Pesci, Lorraine Bracco, Paul Sorvino. Directed by Martin Scorsese. Aspect ratio: 1.85:1 (widescreen). Dolby Digital 5.1. 146 minutes. 1990. Warner Home Video 12039. R. $24.99.

It is an epic gangster melodrama of white-hot passion and blood-red mayhem. It is a darkly hilarious comedy of bad manners about unbridled appetites, lethal impulses, and ill-directed ambition. It is an absurdist satire of middle-class morality gone perverse, voracious consumerism as a way of life, and the ties that bind only until they're hacked off or blasted away.

It is all these things, and it's called GoodFellas. More than a decade after it blasted its way into the pop-culture pantheon, it remains—arguably even more than Francis Ford Coppola's great Godfather triptych—the touchstone for all subsequent mob movies, and a prime influence on everything from Analyze This and Mickey Blue Eyes to Donnie Brasco and TV's The Sopranos.

It is all these things, and it's called GoodFellas. More than a decade after it blasted its way into the pop-culture pantheon, it remains—arguably even more than Francis Ford Coppola's great Godfather triptych—the touchstone for all subsequent mob movies, and a prime influence on everything from Analyze This and Mickey Blue Eyes to Donnie Brasco and TV's The Sopranos.

This teeming saga of life and death among midlevel Mafiosi is consistently electrifying, charged by director Martin Scorsese (Taxi Driver, Raging Bull) with alternating currents of wonderment and repulsion. Like Henry Hill, the movie's protagonist, viewers may be amused at first by the swaggering vitality of these villains. But Scorsese then rubs our noses in what these people really are all about, and even Henry is aghast.

Working from a screenplay he co-wrote with Nicolas Pileggi—author of Wiseguy, the memoir on which the movie is based—Scorsese dramatizes three decades in the life of Henry (played by Christopher Serrone as a teenager, Ray Liotta as an adult), an Irish-Sicilian Brooklyn kid who greets us with a simple, heartfelt statement: "As far back as I could remember, I always wanted to be a gangster."

Henry begins as a gofer for neighborhood hoods, and impresses them enough to be "adopted" into their family—even though, because of his Irish background, he can never be accepted into the Mafia hierarchy. He begins as, and remains, an observant outsider, which makes him all the more useful as the movie's narrator.

Right from the start, Henry appreciates the value of having good friends in low places. When Henry's parents are informed of their son's frequent truancy, mobsters warn the neighborhood mailman not to deliver another letter from the school board.

Later, Henry strides past the round-the-block line of waiting customers and into the side door of the Copacabana nightclub with Karen (Lorraine Bracco), his future wife, on his arm. He doesn't have to wait—other people have to wait on him, because "being a gangster is like being president of the United States." It's a stunning sequence, a long continuous shot propelled by Scorsese's breakneck virtuosity and Michael Ballhaus' relentlessly gliding camera.

In that scene and elsewhere, GoodFellas is about nothing so much as the rush, the juice of feeling totally confident, totally in control, one of the chosen few. Trouble is, that exuberance can turn toxic. On the final day of his freedom, Henry races through a sardonically twisted yuppie-Mafia nightmare of balancing home life and career. He frantically divides his time among preparing a lavish family meal, visiting his mistress, delivering stolen guns, avoiding a pursuing helicopter, readying a drug shipment—and repeatedly charging himself with cocaine. As always, Scorsese picks the perfect pop tunes to underscore the sequence. Ry Cooder's slide-guitar intro from "Memo From Turner"(which originally appeared on the soundtrack of Performance) dips low and ominously as a coke-addled Henry lurches deeper into paranoia. Then Harry Nilsson's "Jump Into the Fire" explodes in our ears, and the harshly yelped lyrics—"You can jump into the fire, but you'll never be free!"—have the impact of a slap across the face.

Henry has two Mafia "brothers," neither of them reliable. Tommy DeVito (Joe Pesci) is the more obvious sociopath, a volatile hothead who will shoot a waiter in the foot for fun, then shoot him through the heart when the wounded fellow makes a rude remark. But James Conway (Robert De Niro) is even more dangerous in his cold calculations, especially when he begins to exterminate his partners in crime.

The performances are everything they need to be, and much more. The chronically underrated Liotta is riveting as Henry, the ambitious outsider who recognizes far too late the bloody underpinnings of his romanticized Mafia fantasyland. De Niro is subtly imposing in what is basically a supporting role, while Pesci—who won a richly deserved Oscar for his performance—is at once hilarious and horrifying as Tommy, a loose cannon ultimately destroyed by the bloody ricochets of his own violence.

This is a man's world, but Lorraine Bracco (who takes a more analytical view of mob life in The Sopranos) asserts herself as dynamically as the character she portrays. When Karen tires of her husband's infidelities and threatens him with a gun, Bracco makes you believe that, hey, she might actually pull the trigger.

GoodFellas runs nearly two and a half hours. Not one minute is wasted, and not one second rings false.