Aspect Ratio Oddities Page 2

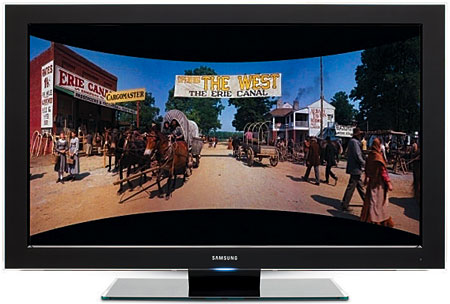

How the West Was Won Smilebox

Of course, it’s not a perfect simulation. During the movie’s production, each of the three Cinerama camera lenses was angled in a different direction. The center lens aimed straight ahead, and the left and right lenses each aimed diagonally toward the opposite side. In theatrical exhibition, the three projectors (named Able, Baker, and Charlie) were arranged likewise. The leftmost Able projector shone onto the far right panel of the curved screen. Baker shone straight ahead, and Charlie (on the right) projected toward the left panel. Because of this unconventional process, both the flat letterbox and the SmileBox simulated curve have some degree of geometrical distortion, but in different ways. You can see this 9.5 minutes into the film when Jimmy Stewart paddles a canoe from screen left to screen right. When he hits the right-hand panel, the shape of the canoe seems to warp and bend away from the camera in the letterbox transfer. However, the boat moves in a fairly straight line in the SmileBox image. Elsewhere, a three-shot of characters at time code 2:26:07 looks normal in the letterbox version but is very oddly stretched in SmileBox. In the latter, Debbie Reynolds looks like she’s been flattened into a two- dimensional cutout and pasted onto the left side of the screen.

Each version has its own strengths and weaknesses. SmileBox doesn’t win everyone over. Former professional projectionist Vern Dias claims to have seen How the West Was Won in its original three-panel Cinerama more than 20 times. To him, “SmileBox approximates the view looking through the doors from the lobby or sitting in one of the rearmost rows of seats in the theater.” Dias says, “My favorite seat and the choice seat for full involvement in the action was to sit dead center in the row of seats that roughly lines up with the chord of the arc that the screen creates. This usually meant row 7 or 8 from the front but was dependent on the individual theater. This seat would closely correspond to the position of the camera when the movie was originally shot. When you sit in this sweet spot, you are located almost equidistant from all points of the screen, and the height at the center of the image does not appear to be significantly less than the height of the sides.” For the Blu-ray release, Dias prefers to watch the letterbox transfer on his front-projection screen.

To this, Strohmaier counters, “Every effort was made to do this SmileBox process correctly up to and including projecting 1962 historic three-panel Cinerama/MGM focus charts on the actual 146-degree Cinerama curved screens at the two existing Cinerama locations. This became the template for the SmileBox process. It was developed with very great care by people who knew and cared deeply for what they were doing.” In the end, the two aspect ratios for How the West Was Won come down to personal preference. Both are valid in their own ways. Thankfully, Warner provides both versions in the Blu-ray package.

Letterboxing was first introduced for home video with the long-defunct CED disc format. Back in 1984, Federico Fellini’s Amarcord was released on CED with letterbox bars to maintain its 1.85:1 theatrical aspect ratio on the 4:3 TVs of the time. The process had been previously used for selected scenes in movies (usually opening credits), but never for an entire feature. A few months later, Woody Allen’s Manhattan followed on both CED and Laserdisc. At first, many people had trouble understanding the concept. If stories from the time are to be believed, a large number of consumers returned their copies. They believed the discs were defective because they didn’t fill their TV screens. Eventually, Laserdisc, DVD, and Blu-ray made letterboxing a standard practice for any movie whose photography didn’t quite match a TV’s shape. These new developments with changing or oddball aspect ratios serve the same purpose.

Despite the many years it took to get used to the idea of letterboxing, people still ask why movies are made in different aspect ratios. Why don’t all movie studios standardize their filming formats to 1.78:1, which will fill an HDTV screen when their products come to Blu-ray? The choice of aspect ratio is an artistic decision made by the director and cinematographer. Would the sweeping epic vistas of the Lord of the Rings trilogy have the same impact at a narrow ratio? Conversely, would the Godfather saga feel so intimate if it had been shot wider? Each movie has its own artistic needs. The goal of home theater isn’t to fill an HDTV screen. The television is just a picture frame. The movie is the artwork. If the art doesn’t fit precisely into the frame, some matting may be needed to dis- play it properly. As filmmakers con- tinue to experiment with the forms their art takes, new types of matting may be needed.

- Log in or register to post comments