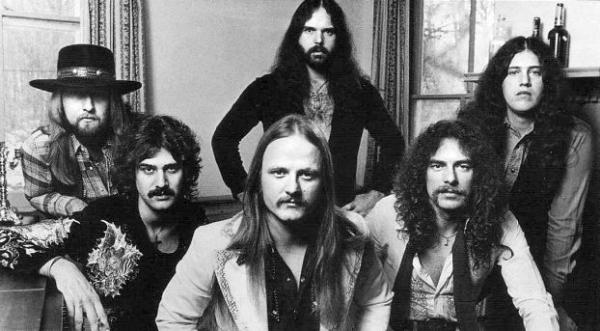

38 Special Keeps Rockin’ Into the Night

More than that, 38 Special fused those influences with their own original pop-meets-rock-at-the-crossroads sensibilities to forge an indelible string of hits including “Hold on Loosely,” “Fantasy Girl,” “Caught Up in You,” and “If I’d Been the One,” to name but a few. And the band’s legacy continues to roll ever onward, with Barnes currently on the road this summer fronting 38 Special while Van Zant, essentially retired from both the band and the live stage, is all excited about the imminent July 1 release of a live album from Van Zant (the band he formed with his brother Johnny Van Zant) called Red White & Blue (Live) (Loud & Proud Records).

RW&B(L) was recorded on January 28, 2006 at Wild Adventures Theme Park in Valdosta, Georgia by onetime 38 bassist Larry Junstrom (a.k.a. “LJ”) with his own mobile recording equipment. Besides Van Zant country-chart hits and a few Lynyrd Skynyrd staples, the album also features Johnny taking a crack at the title track to 38’s hit 1981 album, Wild-Eyed Southern Boys. “It’s just about the first time I ever sang it!” Johnny told me recently. “And that’s a cool thing. I got a lot of enjoyment out of doing that.” And even in semi-retirement, Donnie Van Zant says he’s still got the fire: “Well, I gotta be true with you, sir — I only know one volume, and that’s 10.”

Recently, I got on the line separately with Van Zant, 63, and Barnes, also 63, to discuss the rich musical history of 38 Special and their hometown of Jacksonville, Florida, working with Dan Hartman as their early-era producer, and their respective legacies as both songwriters and performers. They’re just two wild-eyed Southern boys caught up in making some good ol’ rock & roll for anyone who’s willing to listen.

Mike Mettler: Donnie, would you agree the phrase “The first family of Southern Rock” applies to you and your brothers Ronnie [the late lead singer and chief songwriter of Lynyrd Skynyrd] and Johnny [current Lynyrd Skynyrd lead singer and Donnie’s partner in Van Zant]?

Donnie Van Zant: You know what? I’ll let other people reply to that. We try to do the very best we can.

Mettler: Well, so far, so good, I think. A lot of that is in your DNA, literally, as you had a strong parental unit with your mom and you dad behind you while you were growing up. You had respect for your family, and I think that goes a long way in coming out in what you guys do musically.

Van Zant: Oh, big time, brother; big time. We had parents who were totally supportive of anything we wanted to do. They didn’t care what exactly we did — whether we drove a truck, painted houses, or worked at a grocery store — as long as we did the very best we could do. That was what was important to them — always put in the effort, and try to be the best that you can be at whatever. They instilled that in all of us, and in my sisters too.

The truth of the matter is, we grew up on country. My dad was a long-distance truck driver and my mom was a manager of a Dunkin’ Donuts shop. Back then, if your dad drove a truck, that’s what you listened to — country. Mel Tillis, Hank Williams, Faron Young, and George Jones were the people we listened to. We were very influenced by all of that. Johnny Cash was a real big one too. We just loved that rebel feel from him! (laughs heartily)

Mettler: Jacksonville seems like it was such a hotbed for music when you were growing up there in the ’50s and ’60s.

Van Zant: It sure seemed like it. That’s what I’ve always said — there was some good water here, that’s for sure! (laughs) It’s really wild. It was blue collar, working class people. Where we grew up, on the west side of Jacksonville, was a pretty rough side of town. Most of my buddies I grew up with either ended up dead or in prison. Thank God we got into music, and moved away.

Mettler: “Dead Or in Prison” — I think that’s a song for your next album. (Van Zant laughs) So you could just ride your bike down the street, and you’d be at one of the Skynyrd boys’ houses, just a couple blocks down?

Van Zant: That’s correct. And with 38, you’re talking about three members of the group who actually lived on the same street, Woodcrest Road. Well, there was actually a line dividing us from where Don Barnes lived, and that was called Lake Shore Boulevard. And as Don would tell you, you don’t cross Lake Shore Boulevard and go to the Van Zant side, because it was very dangerous! He was on the same side! (chuckles)

Don Barnes: That’s right. I used to ride my bike to Allen [Collins, co-founding Lynyrd Skynyrd guitarist]’s house. He had all those great guitar licks, and we’d listen to old British import records.

Jacksonville was a navy town, so all those guys from Duane Allman to Gregg Allman to Ronnie Van Zant and all those other bands — Molly Hatchet, The Outlaws, and the guys in Blackfoot, all living right down the road — we all played sailor’s clubs at 15 years old. When you can make 100 bucks a week at age 15, that’s big money.

We learned all the structures of those songs in the early days as kids, because you had to learn the hits of the day from the radio, and you found what the actual craft of building a song was. There’s an A section, and a little ramp that goes to the chorus, a bridge, and an outro — all those things. You find what’s the big payoff on those things. Of course, then you get cocky and you go, “Well, I’m going to write my own songs.” And then you starve for 10 years. (laughs)

Mettler: That’s called paying your dues.

Barnes: I don’t highly recommend it! You gotta sacrifice so much. If you have some stability to fall back on, you should probably do that. There are no guarantees. You have hopes for some songs where you think, “Oh, this is going to go all the way.” And it doesn’t do it. But one that you might have a lot of hope about actually does click.

Mettler: If Skynyrd was considered one of the backbones of ’70s rock radio, then 38 Special was one of the backbones of ’80s rock radio.

Barnes: We’re fortunate to have had 15-16 hit songs throughout the years, a couple #1s, Top 10s, Top 20, Top 40, whatever — people relate to those songs. You know how that whole thing goes. People go, “Man, I remember what I was doing when that song came out.”

Mettler: I think one of the reasons you got a lot of airplay had to do with the ways you were able to blend melody and harmony, which definitely reminds me of a certain Fab Four across the Pond. Those touches appear in your own songwriting.

Barnes: Yeah, we were big fans of them. Coming from the South, it’s automatically assumed you’re going to sing bluesy stuff about bad whiskey and women. We also learned a lot from Ronnie Van Zant, from the early Skynyrd days.

Mettler: Is there any one Beatles song that still stands out to you today, as a songwriter?

Barnes: Well, I always liked the more “power” stuff when they came out. They got a little eclectic, artistic — Paul McCartney, with his dad’s influences, and the skiffle stuff. I liked the early days — just real powerful (sings), “Any time at aaa-alll!” [from 1964’s A Hard Day’s Night]. So we fashioned our sound after that.

We had done an early album that was basically rehashed Southern rock, but it had already been done by the best — The Allmans, Skynyrd, and everything. But Ronnie Van Zant, he said, “Don’t be a clone of someone else. Don’t copy what’s in front of you. Take on your own influences and be true to what you like. And if you like more of a pop element, then try to explore that.” And that was some good advice. We had gone down the road with a couple of albums that had been panned, which were kind of the same thing.

Mettler: Well, I’m still partial to your 1977 debut album [38 Special] that has songs like “Long Time Gone” and “Fly Away” on it.

Barnes: Ohh! Well, that’s great! (chuckles) You remember that long ago!

Van Zant: Uh huh! Oh man, thank you so much! I don’t hear that very often.

Mettler: That album and 1978’s Special Delivery were both produced by Dan Hartman. I think people don’t realize he was a pretty good producer back in the day, not just the guy who wrote and sang “I Can Dream About You.” [Hartman’s 1984 solo hit “I Can Dream About You,” from the Streets of Fire soundtrack and later the album of the same name, reached on #6 on the Billboard Hot 100 singles chart.]

Barnes: Yeah! We didn’t have many people coming and recording us back then because we were young and green, so they said, “Well, this guy Dan Hartman — he wrote ‘Free Ride’ [for The Edgar Winter Group, in 1973] and sang it, and has his own studio in his house.”

Van Zant: Oh my God, yeah. What a talented guy he was. I learned so much from him. I mean, I didn’t believe how much I didn’t know. Being around Dan, you just ate it all up, that’s for sure. Unbelievable musician, and just a great teacher. He taught me so many different things.

We went up there to Connecticut for those first two records 38 ever made, and we were just getting started. We were very green, and he helped us out, all of us.

Barnes: We had a great experience with him. He had his own studio in Connecticut called The School House. A big room was built onto the original school house, and he made a studio where you could put an amp in the bathtub and run an out right from there, because the whole house was wired. You could get all these great sounds from hard surfaces and acoustic tiles.

We had a great time. We lived in his house, and he was a good guy. It was a sad ending for him, but we did a couple of good albums together. [Hartman passed away at the age of 43 on March 22, 1994, of an AIDS-related brain tumor.]

This guy was so multi-talented. We would wake up and come down to the den and hear somebody playing like Hendrix, with the amp low-tuned. He could play like Hendrix. And then he’d sit down at the piano and play all these Elton John songs. He loved the Philadelphia Soul — that’s why you can hear it in “I Can Dream About You.” He loved The Spinners, and all those guys. He was like a sponge; he soaked up all those influences. And it was amazing to see the guy be such a virtuoso at every instrument — singing, playing, producing, piano, guitar. And he played bass in Edgar Winter.

Mettler: He could do it all.

Barnes: We have some good memories about that. We went to Edgar’s house — he lived in Westport also — for him to put a sax solo on one of the early songs [“Can’t Keep a Good Man Down,” on Special Delivery]. Edgar just floored everybody with the first take. We thought it was great and we were getting ready to leave, but he’s such a perfectionist, so he went, “Well, let me try it again,” and he’d do nine or ten passes at it again. We kept the first one, because it was so spontaneous. But he is truly a genius, Edgar is.

Van Zant: Somebody asked me what was my favorite record of ours — I don’t actually have favorites. Any song that got onto a 38 or Van Zant record, I had to feel they were “A” songs, or they wouldn’t have made it anyway.

Mettler: That’s what I liked about the records you guys made back in the day. Each album was 40-ish minutes, and every song was worth being on there.

Van Zant: That’s right. The way I looked at it, you wanted to give the people their money’s worth. I remember buying records where there’d only be one good song.

Mettler: And then you felt like you got ripped off.

Van Zant: You did! You felt like you got ripped off. You bought the whole record for one song. We thought just the opposite of that. We’d write 50 songs to get 10.

Mettler: That’s the mark of being good editors, something I think got lost in the CD age. We all love the convenience of CD and digital, but having a good solid 15-20 minute side that you can put the needle down on and then flip it over was where it was at for me.

Van Zant: You know, it’s weird you say that, because I just did that the other day. I actually went out and bought a record player again. I have a collection of records I’ve kept over the years, and it was cool to hear that sound. For one thing, it was a little dirtier of a sound. It wasn’t so clean, like digital.

Mettler: What was the first record that had impact on you growing up?

Van Zant: From other artists? I was a big Eric Clapton fan — I love Derek and the Dominos. My favorite song is “Layla.”

Mettler: Can’t go wrong with that. I love the piano coda Bobby Whitlock added at the end of it.

Van Zant: Oh sure, and Eric is such a great singer too. I loved all that. I also love the blues. If it had some heart and soul to it, I loved it. The only type of music I never got into was opera. Couldn’t get into it, but I learned to appreciate it.

Mettler: What did you put on the turntable you just got?

Van Zant: You know what — it was actually an old 38 Special record. It was a song called “Stone Cold Believer” [on 1979’s Rockin’ Into the Night]. That, and another song called “You’re the Captain” [on the same album]. I didn’t know if I could remember them, but it was cool to put them on and listen to them.

Mettler: I don’t think I have that one on vinyl, so maybe we can get Universal/A&M to re-release the 38 Special catalog in a 180-gram vinyl box set.

Van Zant: Vinyl’s made a nice comeback, brother. I’d buy that one, right there.

Mettler: Me too — that makes two sales right off the bat. (Van Zant laughs) I’ve seen a cross-section of generations in the 38 Special audience in the last few years, especially recently. You’ve got plenty of younger faces out there looking back at you.

Van Zant: Even 3 or 4 years ago, the audience that came to out shows was very broad; that’s all I can tell you. People our age and older, we had teenagers, and that music crossed over to a lot of different age brackets. Again, it’s because they were live, real songs, and people related to that. It’s the reason Lynyrd Skynyrd got so big. My brother Ronnie wrote songs about truth — songs about what he lived and what he saw other people go through. As long as you live by that and write about that, people can see it.

Barnes: We come from that Skynyrd school of going out there like a football team — being triumphant, and winning the night. Most people go out there to party and have fun — we do that too, but at the same time, it’s all serious work getting the job done.

Mettler: There’s something to be said in this day and age for a band going out there and actually singing and playing real instruments on real songs that they wrote themselves.

Barnes: Kevin Cronin [of REO Speedwagon], we talked about that, the last time we got together. People come up and say, “I can’t believe you guys actually sing these songs, and you play your own instruments!” Well, that’s what you’re supposed to do! (chuckles)

That’s what we started out doing. It becomes a bit of an anomaly after so many years. You hear people track with sequencers and all that, so when real guys come out, the people come out, and they appreciate that. We’re bringing all of the history and all of the hits, the catalog, and the career. And unfolding that history brings a lot of people joy and a lot of happiness.

A longer version of this interview appears on Mike Mettler’s own site, soundbard.com.