The Retro-Cool Analog Vibes of Nick Waterhouse

It’s a typical story: Boy meets vinyl. Boy falls in love with vinyl. Boy buys tons of vinyl. Boy learns how to write music. Boy eventually makes his own vinyl.

Okay, well, perhaps it’s not the most typical story there is, but it’s a story that most aptly describes the life arc of one Nick Waterhouse, the retro-cool singer/guitarist from Southern California who’s absolutely mastered the art of analog presentation on wax. (Working at Rooky Ricardo Record Shop in San Francisco during his younger days certainly didn’t hurt either.)

On his self-titled fourth album, Nick Waterhouse (Innovative Leisure), the soulful, genre-bending songsmith brings all the worlds he loves as an artist together on his preferred format, 180-gram vinyl (though digital and CD versions are also available). “This album had a couple of working titles while I was doing it, but when I sequenced it, I realized it was a statement,” Waterhouse explains. “The last three albums I made were almost like developing three different muscle groups, and this one is just an execution of everything I had learned over the last three.”

To that end, Nick Waterhouse percolates and hums along like a retro-chic dream by blending blues, R&B, jazz, and timelessly catchy pop into a fine sonic consommé, from the Ray Charles leanings of “I Feel An Urge Coming On” to the hi-hat shuffle manifesto of “Black Glass” to the fully accelerated swinging groove of “Wreck the Rod.”

For Waterhouse, exerting even more control over the proceedings was of paramount concern. “For this album, I finally went, ‘Hey, I have a say in what’s going on here’,” he continues. “I read an interview with Eric Clapton where he was talking about making the Derek and the Dominos record [1970’s Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs]. He said that during the first five years of his career, all he was doing was reacting. He didn’t have any time to think about what he was doing. This album comes from that idea. That’s why I decided to call it my own name, and also to help break out of the trilogy trajectory of the first three.”

I called Waterhouse, 33, at his homebase in Southern California to discuss how an artist’s name can come to define their personal brand of sound, how he reconciled his mono tendencies with making an album in stereo, and the clever but logical way he mixes his passion for both 45s and 33s. I can’t hold back — wreck the rod, and bring the strap. . .

Mike Mettler: You recorded at Electro-Vox Recording Studios in Los Angeles this time around, right? There must have been some kind of a great vibe going on in that studio.

Mike Mettler: You recorded at Electro-Vox Recording Studios in Los Angeles this time around, right? There must have been some kind of a great vibe going on in that studio.

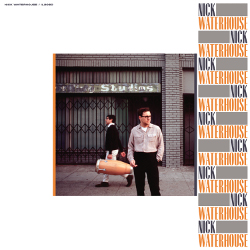

Nick Waterhouse: Oh yeah — and that’s also me in front of Electro-Vox on the cover, out on Melrose [Avenue]. Now that I think about it, my whole career has been about getting into rooms like that. That’s actually the thing I get off on. It’s less than getting accolades or being in front of people (chuckles), but it feels like somebody let me in the back door, or something.

Mettler: I’ve been in a number of studios while artists have been recording, and there’s nothing like being in a room like that whenever a cool new sound comes out of it.

Waterhouse: Absolutely! On the very first day there, “Wreck the Rod” was the very first song we were cutting. We started running it, and by the sixth take, it was like, “Alright, that’s what the room sounds like! We don’t need to touch anything else the rest of the time we’re here!”

Mettler: And you’ve done the perfect retro kind of video for that song too, where you’re dressed in your pseudo-Tony Clifton mode on a vintage talk show. [Sleazy lounge singer Tony Clifton was one of the many alter egos of the late comedian Andy Kaufman, a mantle later picked up by writer and Kaufman confidant, Bob Zmuda. You can watch the video here.]

Waterhouse: (chuckles) Gilbert [Trejo], the director of the video, and I kept talking about that. There were a number of different wardrobe choices, and initially we were going for the Van Morrison-on-cocaine/Last Waltz period [i.e., circa the 1976 movie of The Band’s historical final concert]. (both laugh)

Once you put the prosthetics on me and try to match the hair to what the period would have been, then it unfortunately puts me much closer to Tony Clifton, I think.

Mettler: Somewhere between Van and Tony isn’t too bad, I guess. Tony had his moments as a singer too, sort of.

Waterhouse: That’s true! They also had the same disposition towards show business.

Mettler: Clearly! The swing of that track and the way the girls sing on it shows how you always know how to capture that exact right sense of space that fits the vibe of your material, which really defines your brand, or sound, as an artist. Your name, in essence, now defines what we hear from you, and how we hear it.

Waterhouse: What’s funny is, living in this era, nothing’s really “new,” is it? The concept of a “brand” in the past was more like “Produced by” or “Directed by,” and you would know what you were getting. But now, you would call that a “brand.” (chuckles)

Mettler: Phil Spector had his “Wall of Sound,” so this is the “Wall of Nick,” if we can call it that.

Waterhouse: Sure, that’s fine — trademark it! Or you could call it “The Big Wave.”

Mettler: Oh, I like that too. Your first couple of records were done in mono, but this one is in stereo.

Waterhouse: Yeah, well, Paul Butler co-produced it with me, and Paul is my absolute favorite person I’ve worked with in terms of just matching my energy. I’ve found that I’ve had good working relationships with people in the past, but there was less empathy at times, or I’d wind up fighting. But Paul was someone who ushered himself into this world of mine, and he was in absolute harmony with what my vision was.

Paul is somebody who thinks in stereo, and he would instinctively do stuff in stereo that was really subtle. Most of the times when I’ve worked with people who want to use stereo, they don’t want to use it for space necessarily — they want to use it almost out of obligation, or without much thought. But we did do mono mixes of all this stuff that may make it to a limited-edition LP, eventually.

Mettler: I’m almost predisposed towards hearing your music that way, in mono. You kind of live in-between the era where mono and stereo lived side by side in the late-’50s on into the late-‘60s, though almost in reverse.

Waterhouse: (chuckles) I know, I know! I also think that’s where my mind lives — with a lot of those great records like the ones by The Isley Brothers or Chuck Jackson’s Big New York Soul on Wand Records — those records that had more of that early-1960s, interesting stereo. I think rock stereo was very boring, because it was more like, “Gee whiz, the backing vocals go all the way to the left, and the drums pan all the way to the right.” They were all trying to be cool like The Beatles, you know?

Mettler: You’re right. It became gimmicky rather than best utilizing that sense of space we were talking about. I’d rather hear it used like the way it was done on the vinyl version of Mark Knopfler’s 2018 album, Down the Road Wherever, which utilized the full panorama of the stereo soundfield to paint a full audio picture. It had a sense of depth to it, not, “Hey, look what I can put over here. Look what I can put over there.”

Waterhouse: Sure, and that’s really what Paul was telling me while we were mixing. The tendencies he’s had on the records he’s worked on [including albums by the likes of The Bees, Devendra Banhart, Andrew Bird, and St. Paul and the Broken Bones] have leaned more toward the adventurous and of the mid-century — which is cool, because it offset my own habitual way of placing things. Where I would go, “Alright, that’s how records should sound, to me,” he would be like, “What if we pan this to. . .?” He was actually doing some gentle panning and some spatial stuff that would give the listener more interesting data. Again, my brain is so geared towards 45s, and my rhythm is more rooted in playing 45s on a giant sound system in a nightclub. It was cool. He took that more cinematic feel I had on [2014’s] Holly, but applied it on these songs.

Mettler: Would you say the mix of “Black Glass” is an example of setting up the soundfield like that?

Waterhouse: Absolutely, yeah! “Black Glass” is one of my favorite songs.

Mettler: That one key line in it, “adapt or die,” fits so many things going on right now too.

Waterhouse: I agree! Funnily, that was almost the title of the album — Adapt or Die. But that song was really, really, really the most involved in terms of arranging and production, as I had ten drafts of it where I was adding and subtracting things.

There’s always this thing that happens to me in the studio. I’m still a low-budget artist, so I don’t have many rehearsals when I do these records. I did an arrangement of that horn chart, and I got that in-the-moment thrill of running the concept I had for it initially, and then modifying it and modifying it and modifying it in real time while the people were playing it. That was a song of great reduction, and then addition. And Paul was really all about the spread on that, which really gives a whole other level of drama to it.

Mettler: Yeah, with that cool sax break and the percussion that goes on in the back half of it. And at the end of it, we hear that live-room sound reverberating off of the snare as it fades out.

Waterhouse: Totally. It’s like the audio mis-en-scène.

Mettler: Oh, that’s such a great way of putting it. Getting this album out on 180-gram single-disc vinyl also has to be a thrill.

Waterhouse: Yes, and I was very, very pleased to be working with QRP [Quality Record Pressings] out of Salina, Kansas on it. They’re the greatest.

Mettler: They are. You’re happy with this pressing, then?

Waterhouse: Yeah, it’s beautiful. It’s very high-quality. There was something special about getting those deep-groove pressings with my earlier records, which was very fulfilling. But the new record sounds phenomenal.

And for the mastering, I actually sat down at Capitol [Studios & Mastering, in Los Angeles] when we did this one — which seems highly appropriate, because this one felt very much like a Los Angeles record to me. And that was a nice thing for me, because I drove by that building so many times when I was 15 years old, you know? (chuckles) To be sitting in there the morning before I go on tour mastering my newest album feels like an achievement, like it’s somewhere I’ve snuck into that I’m not allowed to be.

Mettler: I get that. “Which Was Writ” is another track I’m looking forward to dropping the needle down on, I have to say.

Waterhouse: Oh, it sounds gorgeous on vinyl. There’s a lot of depth to it. That was another song I was inclined to do in mono, and Paul convinced me that getting a little more space around it was a good idea. So, again, I’m really interested to see if we’re going to do this limited-edition mono LP, and what that will feel like.

Mettler: There’s a lot of good bass content on that track too.

Waterhouse: And that’s pretty cool, because that was a Fender VI, one of those six-string basses that the second guitarist on the record, John Anderson, was playing. I started improv’ing that line over it — and the next thing we knew, we were having the background vocals sung down the length of the baby grand that we had miked at the other end. That’s how we got that really ghostly backup vocal thing.

Mettler: Yeah, it has that Raelettes/Ikettes vibe going on there, for sure. That’s the first thing that came to mind when I first heard it.

Waterhouse: (chuckles) Right on! I tell people I’m enjoying my career like I’m the last man, like The Omega Man — I’m still making records, because after this, records just might not exist.

Mettler: Well, guys like you and Jack White have to keep doing it, because we’ll keep spinning them. The last time we talked, you told me you had a VPI turntable. Do you still have it?

Waterhouse: I’m looking at it right now! I just got a new needle, actually. It’s a Hana, and I was hipped to them by an audio shop in Pasadena, [California], a fairly new shop called Audio Element. A very nice cat over there turned me onto Hana cartridges. I switched from a Denon [DL-103] big elliptical [stylus], because I needed a stereo needle to play my new record! (chuckles heartily)

I’m also starting to get to the point where I’ve been parsing my record collection. Since I talked to you last, I had to move out for a while after Holly and put everything into storage. Once I got back and situated into a home I could listen to my hi-fi in, I started shuffling through my collection. I have friends who are collectors and record people, and if they have wants and needs, I’m almost inclined to give ’em what they need, if I have it. Yeah, that’s my world.

Mettler: Sweet. Do you still have the rest of the same gear — the Fisher receiver and the Klipsch Heresy speakers?

Waterhouse: The Fisher X-101-B, and the speakers? Yeah. The cool addition to that family is I had an engineer buddy build me a step-up [converter] box that I’ve been pulling transformers from all my outboard gear to use with, which has been really fun. (chuckles)

Mettler: Since we’ve been talking about the differences between singles and albums, do you have a preference between 45s and 33s? Is it more because you grew up listening to 45s?

Waterhouse: Well, it’s interesting in relation to this record. The concept of a 45 is part of the making of an album for me now. I think of songs as 45s still, but that’s also why I was self-titling this one. I was owning up to this being an album, and the idea that I was making an album.

The thing with 45s is, they just sound so much better. They command your attention. I’ve said this since the very beginning of my career — a 45 is like a vote of confidence. You either like the song, or you don’t. You buy it, or you don’t buy it. And that’s even shaped my own editing process. Songs will “die” early — they won’t even make it to the studio unless I’m feeling strong enough about it for it to be its own thing.

Mettler: I always thought of buying a 45 as voting with my dollars. Growing up, you didn’t have a lot of money and you’d buy a 45 of a song that you heard on the radio. You’d play the B-side, and sometimes you’d go, “Hey, I like that too.” You might buy the second single next, but by that point, if I liked four songs by an artist, I figured I’m going to like 10 or even 12, so I’m going to buy the album after that.

Waterhouse: Absolutely! There’s almost like this other set of arcane laws, almost, where the laws of physics are different in the culture of 45s. I mean, I get caught up in how the music business works sometimes. I may have two or three songs I feel are really strong 45s, and my brain is wired to think about artists like [early-1960s R&B vocalist] Charles Sheffield, who has two 45s on Excello [Records], you know? He didn’t have an album, so when should I ever give a f--- about an album? It wasn’t until I ever had to turn in a product that I thought about it that way.

For me, when I’m making an album, I’m able to think of stuff both as an album, and as 45s. To me, “By Heart” is a 45. But it’s also an album opener. It’s a weird thing where songs become sentences in a poem. A line can be really powerful, but the line has to serve the greater structure of the poem, and maybe it’s even stronger by being a part of the entire poem.

Mettler: To me, a lot of first singles are like that — they also serve as album openers, and they introduce us to who you are. That “Put me on, I’m your brand new record album” vibe. “By Heart” is also like that. What’s the line in it? “Never learn something you can do. . .”

Waterhouse: “. . .you can do by heart,” Yeah, yeah.

Mettler: I suppose if we’re really going to go all the way back, you need to do a nice big lacquered 78 one of these days.

Waterhouse: Hah! That’s a bridge too far for me, I think. I think you would be putting people through too much to get to your songs. That’s my rationale. It’s funny — for how esoteric I may seem, I’m very democratic. I’m very much a man of the people.