Moving Pictures: Rush's 1981 Masterpiece Gets its Due in Atmos Page 3

The source of how Chycki brought “Limelight” into the Atmos-sphere lies in his interpretation of the way the song was visualized onstage whenever it was performed live — in this case, by placing Lifeson's sustained chords and nuanced riffing directly into the aural spotlight, as it were. “You saw Rush dozens of times live, so you know what happened every time Al hits that first note of the solo — the stage blacks out, and then all the lights focus on him,” Chycki describes. “At the beginning of that solo section in Atmos, the guitar does this funky, weird motion to simulate that. On the stereo version, you're probably getting a lot of the Dimension D [chorus delay] on the guitars. And even though the Dimension D is a very wide kind of chorus unit, there's no sweep to it, so it sounds chorus-y — and yet it doesn't, which was the magic of that vintage piece. The Atmos mix ended up expanding on that by using similar plug-ins and then getting the height so the guitar just sounds like it's the dome of guitar. Call it 'The Dome of Al'!” Chycki concludes with a laugh. (Knowing all that, now imagine what Chycki will eventually be able to do in order to mimic the laser-driven visual dynamics of “Dreamline,” the kinetic, nomadic lead track from September 1991's Roll the Bones.)

The album's longest track at 11 minutes, the Side II-opening, Pond-crossing travelogue “The Camera Eye” incorporates a truly intricate arrangement that vacillates between its New York and London sections. “The key to the different personality of the two parts are the lyrics,” quantifies Brown, “and, of course, the little cockney interjection in London. This tune was always well-received live — probably because of the sheer energy of the arrangement, great dynamics, and synth colors all coupled with such descriptive lyrics.”

Track 6, “Witch Hunt,” is eternally branded as one of the most foreboding and ominous songs in the band's entire catalog. Interestingly, art director Hugh Syme, a gifted keyboard player in his own right, is the man responsible for its truly haunting synthesizer lines. “I think Hugh was visiting Le Studio to discuss cover concepts with the boys — and, being such a great keyboard player, it made perfect sense to give him a shot at playing on one of the tracks,” notes Brown. “I love his use of the Oberheims to get that rich synth and choral backdrop. As for the 'infidels' [the track's chillingly recurring chanting voices], we got as many of the crew and band as possible to assemble outside on the lawn where we recorded them a number of times until it sounded like a huge, unruly crowd.”

The sense of movement and internalized beliefs inherent to “Witch Hunt” translate to Chycki's favorite “height moments” in the Atmos mix. “From the very beginning with all those textures, you move into this massively huge thing that's now in motion, especially when Neil kicks in and does those huge drum fills from hell,” Chycki observes. “And then there are those really huge, thick synths. To bring it back to the lasers and seeing Rush live, I was visualizing what I was hearing and I got deeply, emotionally engaged while I was listening to it. I looked over at my assistant, who was in the studio with me at the time — he's also a drummer, and he was all teared up. It's become one of my most satisfying moments listening to the record in Atmos.”

While Brown concedes “Vital Signs,” the galvanizing album closer “was the beginning of the departure from classic Rush,” it's a clear-cut musical transition that opened a direct throughline to September 1982's Signals, the last studio album Brown produced with the band. With its reggae-inspired feel and angular, skittery riffage, “Vital Signs” is a surefire beacon for where Rush was heading next. “From a mixing point of view, it took a long time to get the ostinato figured out, because there's so much motion going on, and so many elements to deal with,” Chycki admits. “Rush is a progressive band — progressive — and that means progress. Change. And 'Vital Signs' signaled a clear change. It's such an exciting listening experience — and that's what makes it great.”

Courageous Convictions

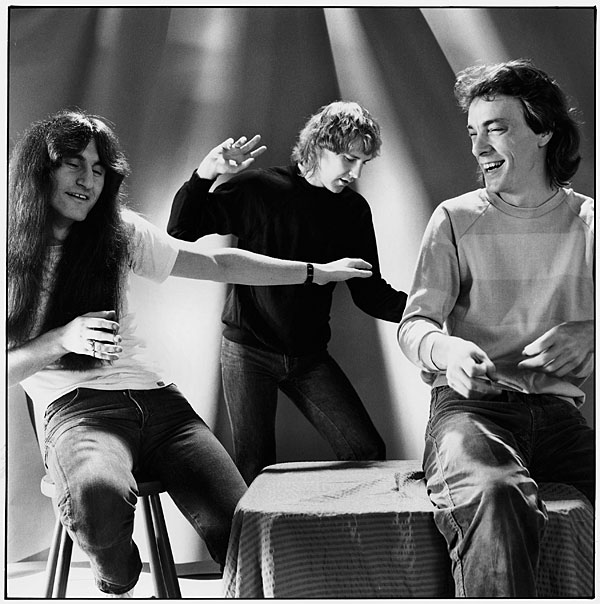

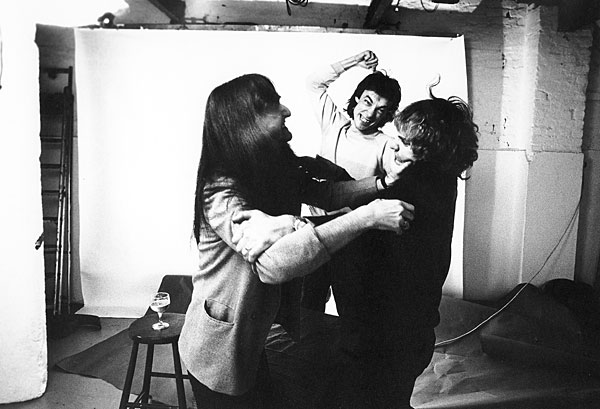

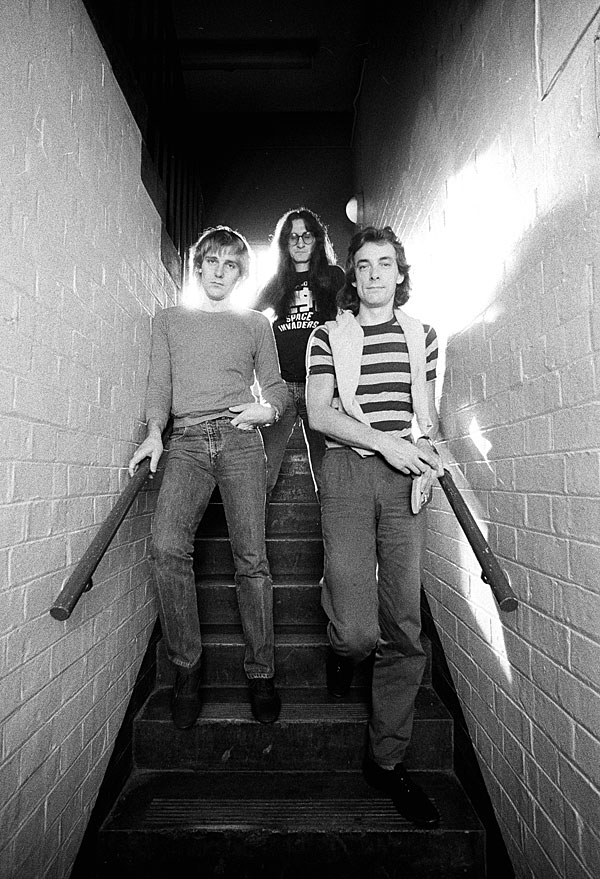

To call Moving Pictures an album for the ages might just be an understatement. “Moving Pictures doesn't seem to have aged,” Brown points out. “It still sounds as fresh as it did when we finished it. It's a combination of great tunes, great performances, and that magical chemistry of three guys who loved to play. During the recording, the boys were always pushing themselves beyond the benchmark achieved on the previous album [Permanent Waves]. It was a very creative and rewarding two months.”

If UMe continues to follow the chronology of Rush's catalog for its Super Deluxe Edition agenda, one can only hope 1982's above-noted Signals will be next on the 40th anniversary slate to get the full-on Atmos treatment. Lest we forget, the template for this maneuver is already in place, given the 5.1 mixes Chycki did for the bonus Signals DVD included in the 2011 Sector 3 box set later transferred into Dolby True HD and DTS-HD 5.1 options for the 2015 Signals High Fidelity Pure Audio Blu-ray edition. Concludes Chycki, “I'd love to do Signals in Atmos. Everybody likes to use the buzzword immersive, and it definitely applies here because Moving Pictures in Atmos draws the listener into a more enveloping listening experience. Atmos is more three-dimensional, and more engaging. It's the next, natural step.”

Some time ago, I asked Geddy Lee what Rush's “secret sauce” was for being in sync, whether they were playing together onstage or when they went into the studio to make records like Moving Pictures. “The secret is, there is no secret!” he responded. “It just requires three people who respect each other and have a willingness to do the things it takes to stay together. It all comes down to respect.”

That unbending, mutually triangulated respect ultimately translated into a body of work that by its very definition, elevated the norm. And when you revisit Moving Pictures, especially in Atmos, you hear exactly how Lee, Lifeson, and Peart captured the true spirit of collaboration. Not content to be a trio comprised merely of players, performers, and portrayers, the harmonic convergence at the heart of all Rush music ensures the legacy of Moving Pictures will last long outside the gilded cage.

For more about the rich and lasting heritage of Rush's ace drummer/lyricist, see “Embracing the Spirit of Neil Peart”.