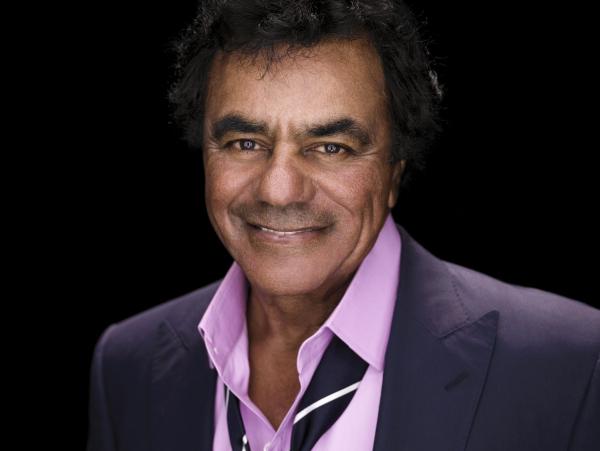

Mettler: “Wonderful! Wonderful!” was a song that was only a single [in 1957; it reached #14], and hasn’t really been available again until now.

Not true. Wonderful! Wonderful! is on many vinyl and CD compilations I have of Johnny's. It's very easy to find.