The 4K Revolution Page 2

Chicken? Please Meet Egg.

The question of when we’ll actually get native 4K content in our homes hangs in the air. As noted in “Hollywood, the 4K Way,” the movie studios are doing their part, scanning many (if not most) new films into the digital domain at 4K or better resolution. Classic back catalog titles are being rescanned and restored in 4K as well. Going forward, new digital movie cameras with 4K or greater resolution will be increasingly used for image capture, resulting in more end-to-end native 4K productions.

But getting those movies into your home theater comes with its own set of challenges. One obvious option might be streaming. As ISF’s Silver points out, 4K is already being delivered right to your computer, courtesy of none other than YouTube. Some of the clips that come up with the search term “4K” have been downscaled to regular HD and are available at a maximum resolution of 1080p, although you can play others at their native 4K resolution. Still, given the current network bandwidth limitations of our country’s infrastructure, delivering full-length movies in 4K with any kind of real-time streaming arrangement isn’t likely, and processing downloads on such large files could be time consuming and memory intensive with today’s tools. Japan and Korea are attempting to develop new 4K terrestrial broadcast standards for their respective countries, but there’s been no movement toward that here in the States. The studios now use encrypted hard drives to deliver movies to theaters for digital cinema, but these won’t be viable as a mass-market option, either.

As with 3D, the best 4K delivery solution for the home is likely to be Blu-ray Disc. “The physical format can do it,” declares Don Eklund, executive VP of technologies at Sony Pictures Technologies, thanks to new compression algorithms. Most notable is HEVC, or High Efficiency Video Codec, which is now in advanced development. It’s considerably more efficient than the AVC codec now commonly used on Blu-rays while remaining similarly free of artifacts, and it will allow a 4K film to fit on a mass-replicated 50-gigabyte, two-layer Blu-ray Disc. “I’ve seen samples of what that codec can do with 4K at a 30-megabit-per-second bitrate compared to what AVC can do at 50 Mb per second, and it actually looks a little bit better at 30 than AVC looks at 50,” Eklund says.

What’s missing, however, is a 4K Blu-ray technical standard that would allow the manufacture of players and discs. Putting that specification together will require a concerted effort by the member companies of the Blu-ray Disc Association. “There are discussions starting, but they’re very early discussions,” notes Eklund. “We just finished 3D, and these things are pretty hard work. But Sony and the other key companies are looking at it very hard.”

Still, the reality is that it’s going to take a while before those discussions bear fruit. With few manufacturers (save Sony) actively promoting native 4K displays for the home and no installed consumer base paving a profit path, other manufacturers and studios in the Blu-ray consortium just aren’t heavily incentivized yet to come on board. It’s the classic chicken-and-egg scenario. And even when the group is unified on a goal, as it was with Blu-ray 3D, it can still take more than a year to develop a standard. Then the manufacturers will have to move the final specification into player hardware as the studios begin mastering discs to it. Translation: Don’t give up hope; we’ll get there eventually. But don’t hold your breath.

There is one more option for driving a 4K display with native 4K content: Make it yourself. A 9-megapixel digital camera—common today—can capture the equivalent of a 4K digital still image. Eklund says Sony’s PlayStation group even worked with the projector division to create a slide viewer for the PS3 that will allow it to send 4K stills stored on the game console to the VPL-VW1000ES for native viewing. And although 4K movie cameras remain pricey professional tools today, Sony envisions a complete 4K ecosystem for the home that will include 4K home movie cameras as well.

Pretty as a (Sharp) Picture

The last step in the 4K chain is the display. Although expensive professional 4K flat-panel monitors exist, as of this writing in late 2011, no television manufacturers have announced firm plans for a 4K consumer display in the U.S. market. That may change at January’s Consumer Electronics Show. If they do arrive, expect to see them around the 60-inch and larger screen sizes, the place where, in Eklund’s words, “4K really starts to come alive.”

Either way, there’s no question the benefits of 4K will accrue most to front-projection systems. The advent of 4K stands to allow larger at-home screens, or, as Cookson noted earlier, the ability to sit closer and enjoy a wider, more immersive image without the distraction of either a visible pixel grid, stair-stepping of diagonal lines, or aliasing on circles or curved shapes. Motion should look more natural, too. With 4K, says JVC’s Klasmeier, “You straighten out the diagonal lines and make shapes look more real, and your brain starts to say, ‘Oh, this is what I’m used to seeing with my own eyes in everyday life.’ And that’s the ultimate goal: You’re trying to reproduce realism.”

For now, it looks like consumers will have more than one path to chase that 4K ideal. Sony’s approach in the VPL-VW1000ES uses three native 4096 x 2160 imagers that generate light using Silicon Xtal Reflective Display (SXRD) technology, the company’s proprietary take on liquid crystal on silicon (LCOS). This late-generation SXRD chip—one each for the red, green, and blue color primaries—measures just under 0.75 inches diagonal and fits a full 8.8 million pixels on its surface. This makes the projector ready for native 4K content and able to accept a true 4K signal via its HDMI 1.4 inputs. Some might deem this purist approach unnecessarily expensive at a time when a home delivery system for true 4K movies still doesn’t exist. The VPL-VW1000ES is priced around $25,000, although Sony justifiably touts this as a breakthrough for native 4K projection. Cost aside, it does theoretically future-proof the projector and ensures buyers will be ready for the day 4K content arrives while still allowing them to enjoy upscaled 1080p images today.

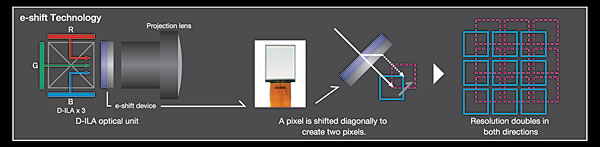

Meanwhile, JVC, another proponent of LCOS with its Direct-drive Image Light Amplifier (D-ILA) technology, has taken a decidedly interim approach to 4K. Several models from the company’s new consumer and professional lines boast a feature called e-Shift, which seeks to deliver the 4K benefit of a more seamless image using native 1080p imagers.

![]()

“We’ve had [professional] native 4K projectors for a number of years, but when we looked, we saw that native 4K content, the delivery and transmission of native 4K, and even the compression algorithms for it just aren’t there yet,” Klasmeier explains. “But there’s a lot of very good 2K content that’s available from Blu-ray. So when we started testing, we realized we can display an image that looks better than a standard 2K image from a 2K Blu-ray with this e-Shift technology. We still get that 4K fill pattern on the screen, but at much lower cost to the end user compared with trying to image at native 4K, where your optics and lens costs go up appreciably.”

Among the 2012 JVC consumer projectors (the custom installer Pro series products are identical but carry different model numbers), e-Shift appears in the top two models, the DLA-X90R and the DLA-X70R, which carry list prices of $12,000 and $8,000, respectively. Developed in conjunction with the research arm of NHK, Japan’s government broadcasting service, e-Shift takes 1920 x 1080 content and effectively displays it as a simulation of native 3840 x 2160. Again, that’s Quad HD, technically short of the DCI 4K spec of 4096 lines. (Note that while both the new Sony projector and these JVC models do project 3D images at full HD resolution, neither can accept a native 4K 3D signal, and only the Sony will upscale full HD Blu-ray 3D to 4K.)

With e-Shift, an original 1920 x 1080 frame of pixels contained in the 1080p signal is electronically doubled to create a second 1920 x 1080 pixel set. Once that’s done, JVC’s upscaling algorithm looks closely at all the subpixels and edits them with the goal of smoothing edge transitions, reducing the stair-stepping effect on diagonal lines, and improving contrast between adjoining light and dark areas.

However, due to the resolution limitation of the 1920 x 1080 imaging devices, the new set of subpixels can’t be displayed on the screen simultaneous with the original pixel set. So e-Shift rapidly flashes the two sets of pixels 1/120 of a second apart, with the second set shifted a half pixel to the right and a half pixel down from the original pixels. The two sets of subpixels are time-aligned to prevent motion artifacts, and the frames change so fast they blend together, effectively eliminating the screen-door effect caused by the grid between the pixels.

Sound familiar? Longtime videophiles may recall that the first 1080p consumer displays were DLP rear projectors that featured a technique dubbed “wobulation,” which did something similar. It allowed the use of lower-resolution micromirror chips to achieve an effective 1920 x 1080 display. But those DLP displays relied on a mechanical operation to physically shift the second set of pixels. With e-Shift, it’s done entirely without moving parts, using a known property of liquid crystals called birefringence that causes light passing through a liquid crystal cell to refract. JVC adds a dedicated liquid-crystal-based e-Shift device to the light path. Simply by applying a signal, it can change the e-Shifter’s properties to switch between straight projection and the refracted projection, thus causing the second set of subpixels to come off at a different angle. We’ll be testing one of the new e-Shift projectors in an upcoming issue to see how well the effect works, but demos we saw at CEDIA in September were promising.

Sit Back, Relax, and Enjoy the Show

As you’ve seen, 4K for the home—and even 4K for digital cinema—is still in its infancy. Sony and JVC have stepped out in our industry’s best tradition and pushed the envelope to bring serious videophiles and movie lovers a new kind of home viewing experience. We’re grateful. And we’re hopeful that other manufacturers will soon follow suit, creating a little 4K industry where there once was none. As they do, Home Theater will be right here to bring you all the latest developments and cast our critical eye on that ever-expanding screen. So pull up your La-Z-Boy, kick out the footrest, and stay tuned.