Cool article! What about the entry door to the room? A standard interior door is going to let out a bunch of sound from the gap between the bottom of the door and the floor. Do you add a soundproof entry door?

Soundproofing 101: How To Keep Your Home Theater Quiet

Sound familiar? Ever wonder what it would take to soundproof a home theater/media room/man cave? Or maybe you’re building a new home or planning an addition to accommodate the theater of your dreams and want to include proper sound isolation as part of the plan.

We called on home theater guru Anthony Grimani and asked him to walk us through the basics of soundproofing. Grimani is president and founder of Performance Media Industries (pmiltd.com), a Novato, California–based firm that designs and engineers world-class home theaters and professional studios. PMI’s specialty is architectural acoustics, which involves everything from selecting bassfriendly room dimensions to adding acoustical wall treatments to managing construction projects and building soundproof rooms. Grimani is also co-founder of MSR Acoustics (msr-inc.com), which supplies acoustical tuning systems and specialty construction materials based on PMI’s designs.

As a veteran of Dolby Labs and Lucasfilm THX, he was instrumental in developing standards for home theater and is credited with developing the Surround EX format for introduction with Star Wars: Episode I—The Phantom Menace in 1999. Grimani is also a longtime instructor for the Custom Electronic Design & Installation Association (CEDIA), which runs an educational program for professional electronics installers and technicians.

Not-So-Good Vibrations

When you think about it, there’s not much to the walls in a typical American home: sheets of half-inch-thick drywall screwed or nailed to 2-by-4 studs. Rap your knuckle on the wall, and it sounds hollow, which explains in part why standard walls don’t do a very good job of containing sound. If the kids are clowning around in the room next to your home office, you hear the ruckus. If they’re playing Call of Duty or watching The Avengers—subwoofer cranked up to 11—you hear and feel the sonic mayhem.

Standard drywall construction has what acousticians call a sound transmission class (STC) rating of 40 decibels; the higher the number, the better the material is at blocking sound. When you crank up your system to experience Jimi playing “Voodoo Child” at concert volumes, it’s easy to hit a very loud peak sound-pressure level of 110 dB. An STC of 40 means a person on the other side of the wall will definitely hear Jimi jamming, and if you were to measure the volume with a sound meter, it would register about 70 dB, which is loud enough to be bothersome. You begin to have an appreciation for how the phrase paper-thin walls came into being.

Grimani likes to compare the walls and ceiling of a home theater to a giant sail. “Think of the drywall as a big tarp that collects the air displaced by your speakers,” he says. On a boat, the sail transmits energy from the wind through a mast to the hull and propels it forward. In a home theater with standard construction, the drywall collects the air and vibrates; that vibration is transmitted through the studs to the wall on the other side or the floor above. (Good luck if either of those spaces is a bedroom.) So most of the sound you hear in the room above, below, or adjacent to a home theater actually travels through the studs that connect the two walls or the joists that connect the ceiling to the floor above. Sound also leaks through electrical outlets, lighting fixtures, and other openings that aren’t properly sealed. And then there’s just shoddy construction with materials that don’t line up, leaving gaps, seams that aren’t caulked, etc.

“Sometimes people think, Well, I’ll just add a second layer of drywall, and that will get rid of the problem,” Grimani observes. “It helps a little but not much. It’s like the difference between using a light sail and a heavy sail—it still pushes the boat forward.” People also believe that putting fiberglass or other forms of insulation in the wall will improve the sound isolation, but it barely does because sound transmits through the studs, not the air. “Air is not a very good transmitter, so shoving a bunch of fiberglass in there won’t make much of a difference,” Grimani says. He notes that you’ll get about the same minimal improvement you get by doubling up on the drywall (more on that in a moment).

Another common misconception is that putting foam or acoustic panels on the walls and ceiling will somehow stop sound from going into the room next door. “That would be the equivalent of putting wood blocks in front of your sail to stop the boat from moving,” Grimani says. “Insane! The wind is going to get around those blocks, hit the sail, and move the boat forward.” Sound absorber panels are intended to control echoes inside a room, not block sound.

Soundproofing 101

It seems there are plenty of approaches to soundproofing that either don’t work or don’t work well, so what does it take to successfully soundproof a home theater?

The science of soundproofing boils down to three things: mass, damping, and decoupling. You can achieve varying degrees of soundproofing by adding mass, damping wall surfaces so they don’t vibrate, and most important, decoupling structures so they aren’t physically connected. “Ideal sound isolation is a combination of all three,” Grimani explains. “The right mass, correctly damped with sufficient decoupling, will give you very good separation between spaces.” And isolation is what you want when it comes to sound systems that pump out enough bass to send shockwaves throughout the house.

Let’s take a closer look at those key ingredients.

Mass. The most common way to add mass to a wall is to double up on drywall, the idea being that the heavier the wall, the less it’s going to transmit sound. But, as noted earlier, simply slapping on a second layer of drywall barely moves the sound isolation needle. Technically speaking, you’ll get an additional 3 dB of sound isolation, which is like barely nudging down the volume on your A/V receiver. In other words, it’s game over when Optimus Prime and Megatron start duking it out an hour after your kids go to sleep. “Mass on its own doesn’t quite cut it,” Grimani says. “Damping and decoupling go a lot further.”

Damping. The idea behind damping is to reduce vibration in the ceiling and walls of a room, which in turn will mitigate the transmission of sound through studs and joists to an adjacent room. There are a couple of options, starting with specialty drywall that’s made for soundproofing. “It’s internally damped with a viscoelastic compound that absorbs sound and vibration,” Grimani explains. “When you rap on it with your knuckle, it’s much more dead sounding than regular drywall, which kind of goes bink bink bink.”

Acoustically engineered drywall is available from several companies in thicknesses ranging from half an inch to more than an inch and includes the Sound-Engineered Drywall (SED) line from Supress, National Gypsum’s Gold Bond SoundBreak XP Gypsum Board, and Serious Energy’s QuietRock line. As you can see in Figure 1, sound-engineered drywall with insulation does a respectable job of impeding sound transfer in the middle frequencies but won’t prevent bass from permeating an adjacent room; in the example shown, the Transmission Loss (TL) at 63 hertz—or how much sound is attenuated at that low frequency—is only 16 dB. “Lowfrequency vibrations just push right through to the studs,” Grimani explains.

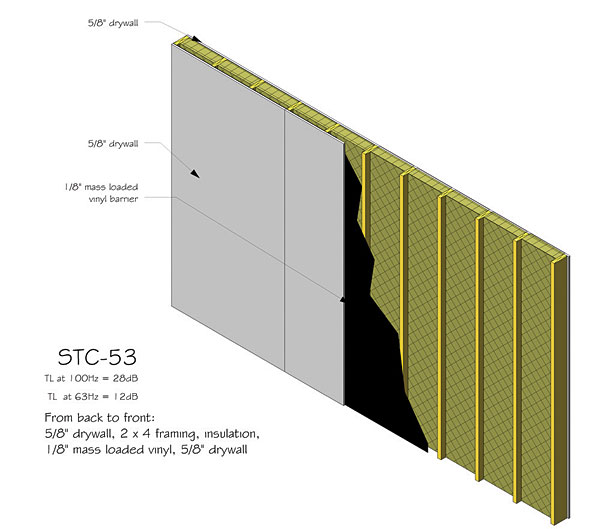

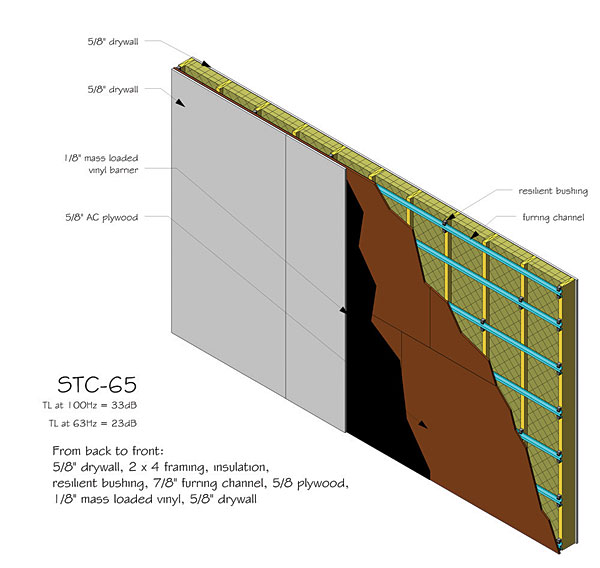

Damping and Mass. The mass-loaded vinyl barrier used in the soundproofed walls shown in Figures 2, 3, and 4 is an eighth-of-an-inch-thick rubbery sheet filled with weighty metal particles that professionals use to add both damping and mass to walls and ceilings. Whereas drywall is a rigid mass that vibrates and resonates, a mass-loaded barrier is what acousticians call a limp mass, which means it’s floppy and doesn’t vibrate; it’s also surprisingly heavy, weighing about a pound per square foot, which makes it tricky to work with. Vinyl barrier is typically stapled to wood studs (or screwed to metal studs) prior to adding the drywall or sandwiched between plywood and drywall as in Figure 3. Just about every company that sells acoustical products offers a version of vinyl barrier; Acoustiblok, made by a NASA spinoff company of the same name, is one of the most common forms of vinyl barrier and comes in eighth- and quarter-inch thicknesses.

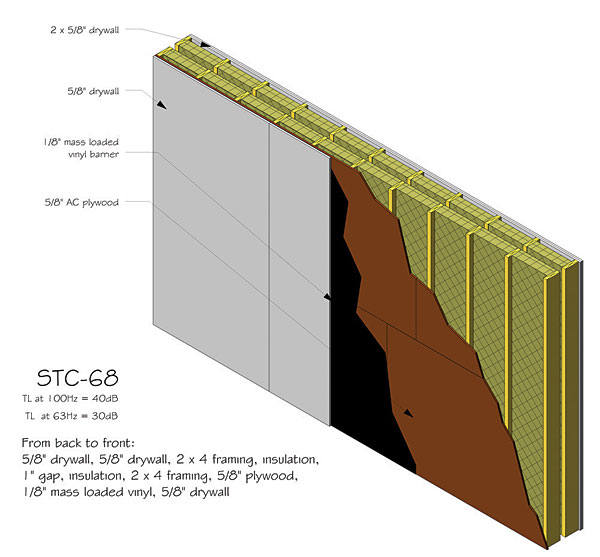

Decoupling. Adding mass to walls and ceilings and reducing vibration through damping provide a good start for soundproofing, but you’ll need to go further if your mission is to contain larger-than-life movie soundtracks. “You need to literally separate, or decouple, the drywall from the studs, preferably on the theater side of the wall so sound doesn’t transmit through the house,” Grimani explains. “It’s a complicated process. You have to literally build two walls, one in front of the other, with two sets of studs.” The drywall on the inside is mounted on one set of studs, then there’s a gap and another set of studs with drywall on the backside to keep the walls totally separate (Figure 4). “Creating a decoupled structure is the only way to really kill the bass,” Grimani stresses. “Adding mass with layers of drywall or even installing damped drywall is just not going to stop bass very much at all.”

The main goal of double framing is to create an air gap between the outside and inside layers of drywall. “That air gap is what prevents the bass from going through,” Grimani explains, “so it’s really important that there are no intermediate layers of drywall.”

Double framing works exceptionally well and is still the preferred approach for what Grimani calls “great soundproofing.” But it is a formidable undertaking—especially if done as a retrofit—and you lose about a foot of your room’s dimensions. Still, it’s a worthwhile investment that offers clear-cut benefits. In addition to excellent sound isolation, you’ll enjoy the unintended consequence of a better-sounding home theater space. “The walls on the theater side are less rigid than standard single-frame walls, so they absorb bass instead of reflecting it, which substantially reduces standing waves,” he explains. “So the problem of bass being really loud in one seat and really quiet in another is eliminated, or substantially reduced, and you end up with a room that has tight, punchy bass just because the walls are not acting as strong reflectors. That’s a nice benefit.”

- Log in or register to post comments

If anyone out there has anything to add, feel free to jump in.

We have lab tested each of our doors in single hung and communicating assemblies. The communicating assemblies are more common in home theaters or recording studios that require a real high level of isolation within a tighter space.

Our doors open and close with a 1/2 pound of force for our heaviest doors (on a smooth operating continuous hinge) and about 2 pounds of force for our standard door (on ball bearing hinges).

The difficult you had closing those doors was likely caused by the sealing system and not the fact they were sound doors. If they were communicating doors (doors installed back to back), then you must relieve air pressure between the two jambs for the doors to close normally.

Anyway, just saying that sound doors are not inherently difficult to operate. They should open and close like a standard door if they are sealed properly and prepared properly for the type of isolation required.

Check out our doors at http://www.soundisolationdoors.com if you want.

Very informative. I had no idea sound proofing took so much effort. Thanks! Reilly

So the problem of bass being really loud in one seat and really quiet in another is eliminated, or substantially reduced, and you end up with a room that has tight, punchy bass just because the walls are not acting as strong reflectors. That’s a nice benefit. Thanks! kmec

What some ways you can sound proof a commercial space with really high ceilings? I have had a few clients that had retail spaces with high ceilings who have issues with it being echoey. Thanks for the post! Nathan Smith

My home theater is in the prestress under the garage. it has 14 inches of cement poured on all side (except the floor, which is 4, but there is just dirt there. So, not too worried about the sound traveling through out the house, except through the duct work, is there any sort of solution for that?

I guess windows and doors also made of the same materials, or perhaps they are also built for sound proofing. I actually seen some sound proof door at caldwells.com/, they have office in Bay Area, San Francisco. It is a glass door type, but this one I know been using at many studio.

Since we need, and want, insulation in the walls what are the pros and cons of spray-foam insulation? It's quite common now, even DIY, and will fill every nook-and-cranny easily. Is thicker better or will the foam act like the studs and actually help transmit the audio to the rest of the house?

I've would have to disagree on this article. Adding mass on the walls will cause echoes in the room. Doubling up on the walls is not feasible for remodeling job and doesn't do more than aid in sound transmission but not complete eliminate it. If you go this route as the article states then you would need to add some sort of wall sound absorbance to it like acoustical panels which you can make at home. Sealing off the home theater complete will create another problem. Air circulation. You would have to put in a return air for your HVAC but it must be running all the time you are in the theater.

I may be buying a new constructed house that has an upstairs bonus room that I want to convert to a dedicated HT room. If the builder has to sheet rock the room, is there anything I can do or have he builder do prior to sheet rock being installed to the studs?? I'm just trying to help decouple the room from the rest of the house with any kind of process to help silence the room once complete. Thanks for any help

It's important to note that the effectiveness of an online Quran academy may vary depending on the specific institution and the dedication of the student. It is advisable to choose a reputable and well-established online academy with positive reviews and feedback from previous learners.

A cavity between teeth refers to tooth decay that occurs in the space between two adjacent teeth. It is caused by the buildup of bacteria, plaque, and acids on the tooth surface, leading to the erosion of the protective enamel layer. This cavity can develop due to poor oral hygiene, excessive sugar consumption, or inadequate dental care.

cavity in between teeth xray

If you are interested in owning a galah, cockatoo for sale make sure that you have plenty of free time to spend with your pet. It is a sensitive bird, requiring a lot of attention and interaction from its owners. As a flock-dwelling bird by nature, if its adopted human flockmate ignores it, the rose-breasted cockatoo can become depressed, angry, and destructive. cockatoos for sale

Birds of varied species and different sizes have variable food needs African grey parrot for sale. The best way to gauge how much you should feed your bird is to watch how much it is eating and discarding. Cockatoos tend to like to play with and toss their food and chew on everything, African grey parrot for sale Melbourne

Situations like as doxycycline ruined my life are uncommon but important threads in the vast fabric of medicinal interventions. They kindly remind us that

Millions of individuals may access a plethora of knowledge and information on Wellliner

London's top Polished Plastering Company specialising in Venetian Plaster & Italian Plastering. Elevate your space with our experts.

Welcome to our veryhealthline, where we delve into the latest wellness trends, debunk health myths, and provide scientifically backed advice to guide you on your journey to optimal health.

Veryhealthline