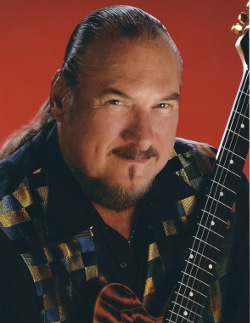

Steve Cropper, Soul Man of the Stax Sound

Steve Cropper is the king of the song intro. One of the chief architects of the legendary Stax Records sound, the once and forever Booker T. & The MG’s guitarist/producer helped put an indelible sonic stamp on classics like The Mar-Keys’ “Last Night,” Wilson Pickett’s “In the Midnight Hour,” Eddie Floyd’s “Knock on Wood,” Sam & Dave’s “Soul Man,” Otis Redding’s “(Sittin’ On) The Dock of the Bay” — and, of course, the Booker T. instrumental masterpiece, “Green Onions.” (That’s some list of prime ear confection right there, let me tell you. . .)

What’s the key to the man’s long-lasting success? To some degree, it was all about timing. “I’ll tell you the secret of what I learned about radio, and you can write it down if you want to,” Cropper says. “I used to sit down and hang out with a lot of these radio guys — and we broke a lot of records on the radio. They came out with this thing where radio stations would not play anything that ran 3 minutes or longer. So this is something we came up with, and we did it all of the time. We’d say, ‘I know it’s too long now, but we won’t go to jail for it.’ We used to put ‘2:59’ on the tape box. Even if it was 3:10 or 3:12 or 3:15, we put 2:59. And the disk jockeys would talk up over the intro until the singer came in, and when it was over, they’d spin another record. In those days, the DJs weren’t watching the clock during their 3- or 4-hour shift, logging the length of every song; they just didn’t do that.”

To celebrate such a storied legacy, Cropper has just undertaken the Rock & Soul Revue Tour with touring partner Dave Mason, which kicked off last week on July 5 in Salina, Kansas. And guitarist/vocalist Mason (Traffic’s “Hole in My Shoe” and “You Can All Join In,” as well as his own solo hits “Only You Know and I Know” and “We Just Disagree”) couldn’t be more excited. “I’d been listening to Booker T. & The MG’s since I was 18 years old, and the list of artists that band has played behind is ridiculous,” Mason, 72, marvels. “I mean, we Brits were basically copying and absorbing what was coming out of America, and putting our own spin on it. For me, to be playing with someone who was such an inspiration to me at this point in my life is fantastic.” Cropper is equally enthused: “I love Dave. Like I told him when we played together a few months ago in North Carolina, it’s been too long coming.”

Besides a mixture of their own respective iconic material, Mason and Cropper will also be playing “All Along the Watchtower” together, a song both artists have deep personal history with. To wit: Mason played 12-string guitar on the original Jimi Hendrix Experience version of this Bob Dylan masterwork on 1968’s Electric Ladyland, while Cropper and the MG’s were Neil Young’s backing band to play the song at the 1992 Rock & Roll Hall of Fame ceremony to honor the induction of the JHE.

To get the scoop on his recorded history, I called Cropper, 76, in Nashville to discuss the process of going from mono to stereo in the studio, the true origin of Sam Moore’s indelible “Play it, Steve!” exclamation on “Soul Man,” and the compositional sizzle behind “Green Onions.” That’s when my love begins to shine. . .

Mike Mettler: When I was listening to the stereo mixes of some of your earlier work, a lot of your guitar lines show up in the left channel during the playback. Was that a conscious decision to do it that way when you were in the studio?

Mike Mettler: When I was listening to the stereo mixes of some of your earlier work, a lot of your guitar lines show up in the left channel during the playback. Was that a conscious decision to do it that way when you were in the studio?

Steve Cropper: It was all because we had two [late-1950s] Ampex mono tape recorders with four channels each. We had eight channels total, and we used the 8th one for echo return. So, you will also hear echo on one side when we went to stereo. What we did was we put the left side on the left side, and the right side on the right side! (chuckles)

Even though we had a stereo machine, we weren’t really able to mix in stereo until we got a console [in the summer of 1965, at the suggestion of producer Tom Dowd] where we had pan pots and could put stuff in the center, the left, and the right, and then put the echo all the way across on both sides. You couldn’t do that with just the two old Ampex recorders.

Mettler: Do you feel you became more creative in the studio at that point because of those studio limitations?

Cropper: Yeah, and you couldn’t fix stuff either. You couldn’t overdub. You could edit — in other words, if Take 2 had a better ending than Take 10, you could put those two things together. You could splice tapes all day long working in mono, but you couldn’t overdub.

Mettler: Do you feel you played better when you were recording that way because if you made a mistake, you’d have to do the whole thing over?

Cropper: I don’t look at it that way. I just learned the process by doing. I once asked another musician, “How’d you learn all those things?” And he said, “Son, you just have to get your guitar, and learn how to play it.” That’s some pretty good advice! (chuckles heartily) How many musicians do you know who took 3 or 4 years of lessons, but couldn’t play anything?

And Tom Dowd taught me everything I know about engineering — how to splice tapes in the early days, and all that. I can still do it, but I haven’t done it in years since we now have advanced Pro Tools. The engineer I’m partners with in the studio is a wizard at it! I don’t want to learn it myself, because it’s hard enough for me to get on the Internet and answer emails! (laughs)

Mettler: Go with what you know. There’s another good song title right there.

Cropper: There you go — “Go With What You Know.” When it comes to coming up with song titles, all I do is call it commercializing something. And I always apply it to fishing. Fish don’t bite on the same bait every day. They just don’t do it. You can throw them something, and they’ll wear it out. Throw it again the next day and they won’t even touch it, so you gotta find the one that they want.

There are some titles on songs a consumer will see and not even touch it: “Don’t even play that for me. I don’t want to hear it.” But give them something commercial that they like, they’ll go, “Oh, yeah, I want to hear that!” (laughs) And if they liked it, they’d ask the disc jockey to play it again, and again.

Mettler: Part of that repeat enjoyment comes from you being the king of the hooks. When you play a song, we know it’s you.

Cropper: I got a desk drawer full of ’em! (Mettler laughs) I always liked to come up with titles for songs that would write themselves. You say the title, and a person can apply that to themselves and write their own story, out of stuff that didn’t exist! (chuckles) It would be about a girl we never met, or someplace we’d never been. That’s kind of what we did, but the title would explain itself.

Mettler: Did you have a list of the titles that would come to you, where you’d write them down somewhere, and then write the song later?

Cropper: At the time, you were writing every day, so you were scrambling. The thing is, people ask me, “Do you still write?” Well, sure I do — I just don’t have the avenue to get the recordings played anymore! But I’m sitting here with tons of ’em. When I’m co-writing with somebody, I’ll pull out the list of titles, pick one, and then we’ll write it.

Mettler: Was it harder to come up with titles for the instrumentals you did in the early days?

Cropper: I don’t think so, and I’ll tell you why. Most of the hits we had, even though some of them had lyrics, the music was as important as the lyrics and the melody. That’s what it was all about for me. We made dance music. It was a lot easier sitting down and play a track without having to worry about words. I did it both ways. I’d take a set of lyrics, write down a bunch of ideas, and then a bunch of verses about that title, and then try to find a groove to put it to. And other times, I would write something that was musically “correct,” and then I’d have to find a title for it and write it that way.

Mettler: They all seem to fit just right, especially when you hear titles like “Knock on Wood,” “In the Midnight Hour,” or “Soul Man.” Plus, a lot of these songs are also very concise, as they tell a full story in less than 3 minutes.

Cropper: It’s kinda hard to do, but you know what? When you’re listening to it, you don’t think it’s that short. And when it’s over, you want to hear it again.

Mettler: If there’s a title that needs to become a song, it’s that infamous phrase, “Play it, Steve!” Was that an improv Sam Moore came up with in the studio when you were cutting “Soul Man”? [“Soul Man” was a #2 Billboard Hot 100 single for Sam & Dave in the fall of 1967.]

Cropper: Totally, totally! That was something Sam said, and I say this in every interview: He probably wishes he had never said it! (both laugh)

Where it really came from was something James Brown had done when he said, “Play it, Maceo!” [“Maceo” is Maceo Parker, Brown’s saxophone player for much of his career.] And Maceo went and had that copyrighted — which spurred me to do that too. I don’t make any money out of it — never did, and never will — but I didn’t write the song. I did co-write the intro with Isaac Hayes, who had come in and asked me to write an intro. But I had nothing to do with the “Play it, Steve” thing.

People ask me, “What’s the hardest session you ever played on?” I say, “Had to be ‘Soul Man’ by Sam & Dave.” They go, “Really? That’s such a great song!” I go, “Yeah, but try sitting down in a chair and not getting up and dancing with Dave [Prater].” That’d be the first thing. The other thing I was doing was I had to balance a Zippo cigarette lighter while sitting, because I played that riff like a slide riff. And I had to stop from keeping myself from moving on that, because that song was grooving on every take. I had to balance that sitting down so it wouldn’t run off my leg! (chuckles) So, physically, it was the hardest session I ever played on.

I will tease the audience about that song. A lot of times, it’s the last song we do in my shows — and I don’t mind doing it. I say, “I’ll bet you that, even if you’re young, 90 percent of you in this audience can name the song I’m getting ready to play in two notes.” All I do is play those two notes and stop — and they go nuts, because they know it’s coming. Then I’ll back up and play the full intro.

And they say, “How did you come up with that intro?” And I say, “I don’t know if I did, but I guess I did.” I was mixing on the day before we had that Sam & Dave session. Isaac Hayes came back to the control room and said, “Steve, I know you don’t like to be bothered, however! I know Dave [Porter] and I have written a hit for the next Sam & Dave session tomorrow, but I can’t come up with an intro. Could you come down to the den and help me out?” And I said, “Well, ok, I guess I can take a little break, since I need one anyways.”

I got my guitar and said, “Play me something. Play me some changes.” He started playing those changes, and I just came up with those licks! And that was it. Man, that’s it! It happened in probably less than 2 or 3 minutes. That intro came to me quicker than it took for me to get my guitar out and plug it in.

Mettler: Isn’t that something? But some of the best songs are written that way, right? They just come to you in a few minutes.

Cropper: That’s correct! And all Isaac said was, “I know we have a hit.” And they did have a hit. They just didn’t have an intro for it, and I was known as “The Intro Guy” because of past songs like “Knock on Wood” and “In the Midnight Hour,” as well as a lot of the instrumentals — they all have gangbuster intros.

I was allowed to hang out at an early age at a lot of radio stations, and I always asked, “Can I come back?” I never really wanted to be a disk jockey, but it fascinated me, the work they did. And like we were talking about earlier, they would talk up until the singer would sing. Whether it was a 10-second intro or a 10-minute intro, they would talk all over that intro until the vocals started, and then they’d stop. And I said, “Man, we gotta fix this!” So I started doing these gangbuster, powerful intros that they couldn’t talk over because it would be too damn loud! (laughs) Think about the intro to “In the Midnight Hour” — BLAM! It hits like a shotgun blast.

Mettler: I think the DJs call that talk-up thing hitting the post. I also remember as a kid, whenever I’d hear them talk over the beginning of songs, I always wanted to hear what was underneath, because it sounded interesting to me. But I couldn’t always tell what it was I was hearing.

Cropper: You had to buy the record to do that — which is a pretty cool thing, because you’ve already gotten into the magic of the whole record.

Mettler: I love how you still appreciate vinyl, which is especially true on your Nudge It Up a Notch record [his 2008 collaboration with Felix Cavaliere] where you have that stack of vinyl on the back, and the turntable on the front. That’s great stuff.

Cropper: (chuckles heartily) I came up with that, Nudge It Up a Notch. I forget what the original title was — we had a bunch of ’em. But that was one of them, with the Victrola on the front. We’d go, “Turn the radio up, nudge it up a notch!” That used to be an old saying we had, but I don’t know where it came from.

Record guys will call me up and say, “I know that song is in the key of such and such, but the record’s not.” And I said, “Well, think about it. We sped it up, and made the master a little more danceable. We didn’t speed it up; we just nudged it up a notch.”

That’s just what we did! We did that with a lot of those records. It’s technology, like “Green Onions” — they can speed it up without changing the pitch. It was exciting, because “Green Onions,” the original record, is not “lame,” but it is slow, relative to what people are used to hearing.

Mettler: And isn’t in a crazy 2/4 time signature, something a little different than the usual?

Cropper: It also has an interesting drum beat. It’s a 2/4 song that goes, 1-2, ta-3-4, ba-ba-4 — that’s in the kick drum, yeah. To all the drummers, I say, “Play that, and just play single quarter notes on the bell of the cymbal” — ting ting ting ting. You do the same thing on the intro to “Soul Man.” That’s what Al [Jackson, the original MG’s drummer] played behind “Soul Man.” Instead of playing the cymbal with the beat, you play with the stick on the side of the bell.

Mettler: That’s a unique Stax sound right there.

Cropper: Well, Al had his own way of playing drums! (chuckles)

Mettler: That makes it its own thing, don’t you think?

Cropper: Absolutely.

Mettler: You’re what I call a “call and response” player. You have these great riff stabs that play off of the other players in the room.

Cropper: Well, Booker [T. Jones] was a genius. He was the keyboard-player genius, and he would come in with ideas, and I’d turn them around and make them easy for myself. And then Duck [Dunn, original MG’s bassist] would come up with something real simple for himself, and got a lotta credit for coming up with all these great bass lines. If Booker came up with something more complicated, we just put it into a dance rhythm; we didn’t change anything. We still had the same changes.

Mettler: And you have such a great tone on “Green Onions,” which I think is also key.

Cropper: What we did on that song was real simple. I had a thing in the middle where the guitar gets 8 bars. Jim Stewart, who engineered it, was the owner of Stax Records. He was the “St” of Stax. [The “ax” was his business partner, his sister Estelle Axton.] He said, “Steve, you know that thing you’re doing in the middle? Why don’t you put that on the intro, and then when it comes to your thing in the middle, just play a solo.” (chuckles) It was just that simple. And that was the take. I did that thing on the front end once or twice at the most. It was probably the second take, after he had made that decision.

Mettler: Do any of those other takes exist somewhere? Could you put together all the takes in the session to show how that song came together?

Cropper: There were probably only about four takes of “Green Onions,” I would think. “Soul Man” was probably about the same, about three or four takes. I think the second one was where Sam said, “Play it, Steve.”

The deal with all that was, in the old days, we cut in mono, basically, and “Soul Man” was cut on 4-track. And whoever wrote it — if Booker wrote it, or I wrote it, or Isaac wrote it, or whoever — we would sit down at the piano or with the guitar, and everybody would learn it. The horns would come down and they would learn their licks, and everybody would learn the song. When everybody went, “Ok, I got it. I know what it is — roll the tape.” So we didn’t have a lot of takes on a lot of songs.

Mettler: You got in, and you got it done.

Cropper: Yeah. I think “Dock of the Bay” was four takes. Somebody decided to put those out, and I said, “Why are you putting those outtakes out?” “Well, it’s considered as art.” And I said, “Well, if I had known that, I woulda burned them!” (laughs)

What we did was we cut the master we wanted from top to bottom, put it on a different spindle, and shelve whatever else it was recorded on. And on that would be those outtakes, unedited — no top, no middle, no nothing; just maybe one splice where a small section was taken out.

Mettler: To me, the value in hearing outtakes like that is you find out how the evolution of iconic tracks like those came to be.

Cropper: Well, I’m glad you appreciate it. I’ve gone into several sessions where the engineer has his head on the console, and he’s twisting knobs and all that, and I would stupidly say, “Could you go out into the studio and listen to what you’re trying to record? Find the right mike for it, and get it that way?” He’d say, “No, this is better. I’m going to make something out of nothing here.”

And they’d do it. They’ll take anything, and just turn it into something else — by computer. (chuckles) And I’m going, “Nahhh.” I like the pure sound myself. I’ve always boasted this, but there’s one of us who’s deceased, and only the two of us know how to mike a French horn. People use them all the time, but they still mike them wrong. They’d be a lot better-sounding and easier if they did it our way! (chuckles)

Mettler: Is vinyl the best way to listen to your music?

Cropper: When I noticed kids were buying vinyl, I thought, “Why?” They want to hear the skips and pops, and I said, “My God, I’ve spent 60 years trying to get rid of them!” (chuckles)

Mettler: It’s more real that way, don’t you think?

Cropper: If they hear that, they know it’s the real deal. They want to hear the crackles and pops, just to validate it. It’s not because they like it, it’s because it it for them.