You are going to own your projection screen a LOT longer than you will own your projector, and the screen has the benefit of NOT going obsolete! Everyone has a budget...stretch yours by investing in a GOOD screen, skimp on the projector if you must, but you will be FAR better off in the long run!

Projection's Reinvention Page 2

If that’s still too rich for your blood, there are plenty of budget 1080p projectors around today that are very good to excellent. For several years prior to 2014, the entry level for any kind of reasonably good home theater projector seemed to hover around $1,500, and it took perhaps twice that to get to the black-level and contrast performance that could make a hardcore videophile start to croon. Today, it seems a bit foolish to spend $3,000 on a 1080p projector that doesn’t at least accept and display native 4K content with pixel shift-ing, but no matter: If a basic 1080p projector is all you need or can afford for now, you can find acceptable performance for as little as $600 and a decent videophile premium model for as little as $2,000. The $1,200 to $1,500 range is a particularly ripe sweet spot for projectors with quite excellent color, reasonably high light output, and average to above-average contrast. They are much improved over their predecessors in that price class of just a couple of years ago.

Pick Your Pic

There are three major display technologies used in today’s consumer projectors: Digital Light Projection (DLP), liquid-crystal display (LCD), and liquid crystal on silicon (LCOS). DLP uses pixel-sized micromirrors arrayed on dedicated micromirror chips (called Digital Micromirror Devices, or DMDs). The micromirrors reflect light toward the screen and oscillate at different speeds to brighten or darken the image. Most DLP projectors employ a single DMD together with a translucent color wheel that spins around to create the red, green, and blue primaries required for a full-color image. Some DLP projectors employ three DMDs, one for each color, and dispense with the color wheel, but they tend to be very expensive. Optoma, BenQ, and ViewSonic are among the popular projector manufacturers who typically employ single-chip DLP technology.

LCD projectors shine a light source through translucent liquid-crystal panels whose pixels can be individually opened or shut down to modulate the brightness. Of course, this is the same technology used in the vast majority of flat-panel TVs today. LCD projectors typically employ separate red, green, and blue LCD panels for the primary colors, hence the “3LCD” branding used by Epson, this technology’s chief proponent.

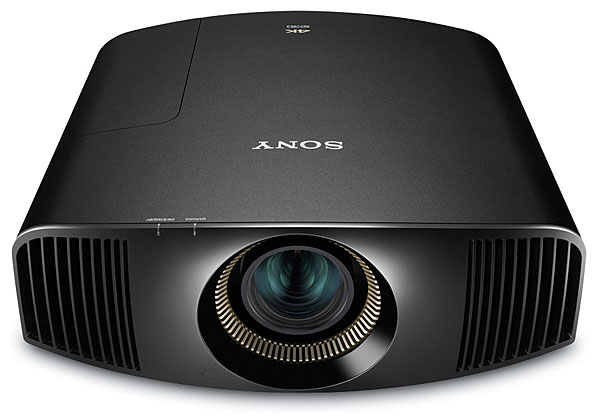

LCOS display devices are similar to LCD panels, but they have a reflective backing: Light comes in through the front, hits the reflector, bounces back through the LCOS device a second time, and is then directed through the lens and out toward the screen. JVC’s D-ILA (Direct-Drive Image Light Amplifier) and Sony’s SXRD (Silicon X-tal Reflective Display) are variants of LCOS.

Naturally, certain characteristics are attendant to each of these three display technologies. But with careful selection, you’ll find high-performing and high-value projectors from all of them. You can check our reviews to see which ones shine brightest, so to speak. But here are a few features and performance parameters to keep in mind as you shop:

Brightness. Projector brightness is usually spec’d in lumens. However, there’s no firm standard for making this measurement that all manufacturers adhere to, so it’s best to use this spec only as a general guideline or for gauging the output of one projector versus another in the same manufacturer’s lineup. Anything over 1,200 lumens will usually be enough to achieve adequate brightness on a 100-inch screen in a fully darkened room, but for high-ambient-light conditions, additional light output might be required. Certainly, with the trend toward HDR among 4K-compliant projectors, more bright-ness is better—though in these projectors or any others, it ideally shouldn’t come at the sacrifice of contrast.

Contrast and black level. The ability to deliver something close to true black is as criti-cal for image quality with projectors as with flat-panel displays. While high brightness can be had in many budget projectors, getting high output with good contrast is more challenging. Better projectors start with devices that have a low native black level, then add a dynamic iris or other technique to modulate brightness and improve contrast. LCOS-based projectors have traditionally delivered the best blacks and have made them a favorite among serious enthusiasts, including the reviewing staff at Sound & Vision, but excellent contrast can be had with well-engineered, premium LCD and DLP projectors, too.

4K content playback. We’ve already covered the difference between native 4K and the enhanced 1080p image provided by pixel-shifting. While native 4K projectors remain pricey, they offer the attractive option of allowing you to enjoy more pristine 4K source material with higher resolution, wide color, and HDR, particularly from UHD Blu-rays. Alternatively, you can simply go for an even less expensive, high-quality 1080p-only model as an interim step before going native 4K.

Low fan noise. In many home setups where the projector gets mounted near the seating, it’s critical for the projector to have a sufficiently quiet cooling fan that won’t interfere with viewing. Our reviews point out when a fan is unusually noisy.

Laser- versus lamp-based light engines. Laser-driven light engines found now in some premium pro-jectors have the benefit of not requiring the regular replacement of expensive lamps, which naturally lose brightness and shift their color pro-file as they age. And laser-equipped projectors aren’t susceptible to damage from rapid or unexpected power cycles, the way lamp-based projectors are. Consider the rated lamp life of any lamp-based projec-tor, and if you’re serious about always getting the best performance from your projector, be prepared to recal-ibrate periodically and replace the lamp prior to its rated half-life. (Half-life is the point at which the lamp’s output is expected to drop to half of its brightness when new, and it depends on how you use the projector—for example, the lamp brightness setting you select.)

Lens and setup options. In permanent installations, setup is something you do once, so the lack of remote-operated, motorized controls for lens shift, zoom, and focus shouldn’t be a deal breaker. But you’ll find this convenience in better projectors, along with lens memories that allow you, for example, to change from a 16:9 image to a widescreen 2.35:1 image with the push of a button. More critical, though, will be the potential lack in budget projectors of lens shift controls, or the burden of an overly restricted zoom range. Make sure the projector you buy will fit your space and mounting requirements.

Short-throw projectors. Some projectors are designed with short-throw lenses that allow placement of the projector close to the screen rather than above or behind the audience. These are primarily targeted for business use, though some 4K-resolution, “ultra short-throw” console-style projectors capable of throwing a 100-inch image from below and just a few inches off the screen are emerging now for living-room use. With rare exceptions (primarily some high-end models from Sony), these so far don’t appear to offer either the per-formance or the value that can be had with a conventional projector and an ALR screen. We’ll be reviewing these models as they become available.

Screen Dreams

Some folks think it’s OK to use a bare wall with white, off-white, or specialized screen paint for a home theater screen. I’ve even seen home theater projectors—usually cheap ones built on a biz-projector platform—that have menu adjustments to change the color temperature to correct for different colored walls!

Don’t do this! Well-engineered screens are designed to reflect back at 1.0 unity gain (or perhaps be more reflective as the situation requires), to optimize contrast, and to provide a smooth, uniform, ripple-free surface. And excellent-performing matte-white screens around 100 inches diagonal that live up to those criteria are available today for perhaps $200 to $300 from high-value manufacturers like Elite Screens, VisualApex (VApex), and Silver Ticket.

That isn’t to say you can’t find good reason to spend more on a screen. The price range cited above is for fixed-frame screens that hang on a wall, typically stretched on a black-felt frame that creates a light-absorbing border around the edge. But if your application requires that your screen be hidden until you need it, a manual or motorized retractable screen can provide a stealth installation—and also protect the screen from damage in a multipurpose room. Retractable screens come in surface or flush-mounted casings, and in tensioned (generally recommended) and non-tensioned versions. But such screens are typically more expensive, not to mention that they often require professional help for proper installation, particularly in large sizes.

There are screens made from acoustically transparent materials as well. And if you require use in high ambient light, there are those ALR screens discussed earlier. Here at Sound & Vision, we’ve been working our way through tests of various ALR screens as they’ve become available. Note that some are stiff panels rather than roll-up screens, and they come in a variety of gains and styles, including a bordered or edgeless look. Some ALR materials are starting to appear in roll-up, retractable formats, however.

Get the Big Picture

Hopefully, we’ve disproven the myth that projection systems are either too expensive or simply no longer serving a useful function in a world of ever-expanding flat-panel TVs. Projectors are affordable, adaptable to different living situations, and still the best path to the big picture. So...what are you waiting for?

- Log in or register to post comments

Had a fairly high end JVC D-ILA for many years and it looked sensational on a 120" Stewart Filmscreen. The problem now is you can't approach the picture quality of a new 4K TV for anywhere near the price.

Yes, TVs are getting bigger and better, but it seems like the industry has simply given up on what was admittedly a niche market, but nonetheless still one with quite passionate devotees who keep buying the product, i.e., 3D movies. Seems that the two big boys, SONY and LG, have stopped offering 3D capable TVs. 4K is all the rage now and so it they have fully abandoned 3D capable sets as of 2017. BUT, if you are a 3D fan like me and quite a number of my friends, we are in luck because the projector manufacturers are still committed to including 3D capability with the higher-end projectors. And if you are enthusiastic enough to be thinking of recreate that authentic cinema experience in your home by considering a video projector as opposed to TV, then the good news is, you will still be able to easily find quite a number of projectors still sporting 3rd dimension capability (you can't get more "movie theatre equivalency" than a big movie screen in your Home Theatre, which relatively speaking is probably bigger than what you see in many a multiplex), but then imagine adding 3D to that wall-to-wall living room screen! Regal, eat your heart out.

Unless something changes in the market place, seems like video projectors will be the only devices capable of presenting 3D content in the future to the home theatre aficionados.

And as far as projection screens...jnemesh has it exactly right -- your screen will most likely outlive your projector, so it's not the place where you want to try to save a buck. I would even go further and say, if you are committed to the movie theatre experience, I would suggest you seriously consider getting an acoustic-transparent screen. You really want to be able to place your speakers BEHIND the screen and this type of screen material will allow you to do just that; TVs, no matter how big, simply don't cut the mustard in this regard. Instead, what TVs tend to do is to force you to wind up using these puny little girly "sound bars" for the center channel -- the channel, BTW, from where the all-important dialog emanates. This invariably causes, the-music-is-so-loud-that-we-can't-hear-what-they-are-saying, syndrome. I can't tell you how often I hear that complaint -- then go check it out and they've got massive left and right channel speakers and not much more than a soundbar with not much more than cellphone-sized speakers in it. I am exaggerating of course, you the point is still valid.

Anyone who has worked professionally with cinema sound design and installation will tell you that the front three speaker channels and speaker systems are ALWAYS IDENTICAL both physically and electrically. That uniformity is essential for the system to produce a stereo soundfield that is cohesive and uniform across the entire screen and will produce sound as close as possible to what the cinema sound mixer heard in the mixing room.

I would also add, not being able to SEE the speaker boxes allows a very interesting psychological thing to happen with the way we perceive audio direction. If you can SEE the speakers, your brain keeps telling you that the sound is originating from that location (which of course it is); hide that visual cue, put the speakers being the screen, and all of a sudden, the space opens up and the sound is much less locked to those points - Left, Center, Right - than when you could see the speaker position.

When I had an Advent VideoBeam in the early 70s (long before there was such a thing as "home theatre,") the screen was fiberglass and speakers needed to be located on either side of it. I felt that the "localization effect" was powerful enough to impair the illusion, so we framed the screen with black chinese silk from the screen edge out to the wall, hiding the speakers; chinese silk is a fabric that was essentially acoustically transparent. It certainly made big difference in helping maintain the illusion that the sound was coming from all points across the entire screen.

Best to luck to everyone attempting to create their own bit of movie magic in their own place.