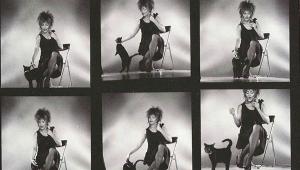

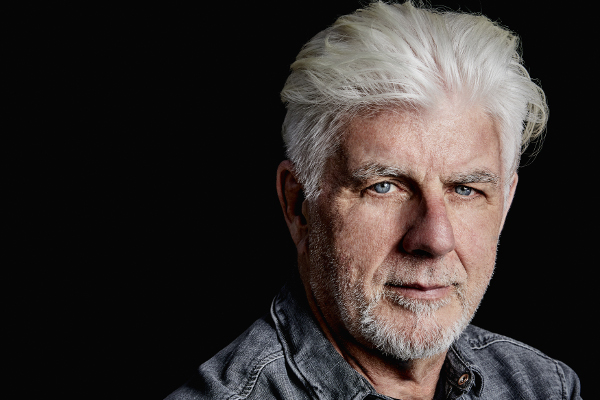

Michael McDonald: Takin’ it to the Seats on a Co-Headlining Summer Tour With Chaka Khan

McDonald (the former Doobie Brothers vocal/keyboard shaman responsible for top-shelf crossover hits like “What a Fool Believes” and “Takin’ It to the Streets” and blue-eyed solo smashes like “I Keep Forgettin’” and “Sweet Freedom”) and Khan (the superfunkified soul priestess responsible for soaring leads on such indelible tracks like “Ain’t Nobody,” “Tell Me Something Good,” “I’m Every Woman,” and “I Feel for You”) are the perfect mirrored bookends to tackle their first extensive tour together for the first time ever. “We’ve played with Chaka in the past at jazz festivals and a few other festivals around the country, but we’ve never had the chance to do an extended tour with her like this, so we’re looking forward to it,” McDonald admits. “She always has a phenomenal band and she’s always a powerhouse, so we’re hoping she’ll help up our game a little bit. I know we’ll be inspired by her, because she’s done that to us in the past.”

Will McDonald and Khan share the stage at any point during their summer run? “Yeah! She’ll do a couple of songs with us, and she and I might do a thing or two together ourselves,” McDonald confirms. “We might even do a couple acoustic things — more like stripped-down moments where there’s no band and it’s just the two of us, you know?” Sounds like a match made in soul heaven.

In addition to talking up this sweet, sweet summer tour, McDonald, 67, and I got on the line to discuss the true secret to his well-respected background-vocal prowess, the compositionally related reason why he was genuinely surprised at the chart-topping success of “What a Fool Believes,” and what his real-time reaction was when he watched Rick Moranis pay, er, homage to him on a vintage episode of SCTV. No wise man has the power to reason away. . .

Mike Mettler: You’ve been a solo performer for years, but the live vocal muscle that you use today must be readied differently than back in your Doobie Brothers days when you had up to three lead vocalists to rotate through during a set. Did you have to prepare your voice in other ways once you began performing as a solo artist?

Michael McDonald: You know, I did. I think as you get older, your voice changes anyway. You have those good periods, then you have those couple of years where you’re not sure what’s happening and you’re just trying to maintain, so you learn to sing differently as you go.

And, of course, I’ve been doing that anyway since I was young. I grew up playing in clubs in St. Louis as a kid, and I learned real quick that you can’t scream like Mitch Ryder every night. (both chuckle)

Mettler: And you can’t be Bob Seger every minute either.

McDonald: Yeah, that’s right! I’ve always been in the process of devising ways to be able to have some stamina as a singer, and also be able to put it over with some emotion. In a way, that’s part-and-parcel with the style I eventually developed. It’s not so much about getting older as it is being an ongoing thing.

I find there’s the good and bad of it. I love singing the whole night and singing a lot of songs, but oh boy, I do miss those days where I only had to sing five or six songs a night. When we play by ourselves, we typically play 90 minutes or longer, and right about the time Drea [Renee] starts to take over singing a verse or two for me during “Takin’ It to the Streets,” I always feel like I’ve just slid into home, you know? She’s a phenomenal singer. My wife Amy [Holland McDonald] goes out with us too, and it’s nice when they take over a verse or two. I really do rely on those other singers. That little bit of rest means a lot when you’re in the middle of a show.

Mettler: You do need that kind of break during those longer sets, I’m sure. Going back to your early days in St. Louis — singing was always in your DNA, because your dad was a singer too. People would call out “Danny Boy,” and he was the man to answer that call.

McDonald: That’s right — that was his big number, every time. He sang around at all the different pubs and saloons in St. Louis, and mostly just for the love of it. It would usually be him and a piano player, and me playing the banjo. He did everything from ragtime music to ballads.

Mettler: I imagine you took a number of your vocal cues from watching him. Did you just know you wanted to sing too? Was that a natural choice for you?

McDonald: I think so. It was his influence, in the beginning. I was four when they put me up on a bar, and I sang a song. And they clapped, because I was cute — and I thought they thought I was the sh--, you know? (both chuckle) I was up for it from that point on.

Mettler: You were a live jukebox at that stage in your life.

McDonald: I was, and it was a lot of fun to play with my dad. It was the one thing we had in common — the music.

Mettler: You said you played banjo. Was that the first instrument you picked up and gravitated toward?

McDonald: I played tenor banjo, yeah. My dad came home one day with this beautiful Gibson banjo that had belonged to his father, and his grandmother had kept it in the attic. It was pretty pristine from when my grandfather had bought it new in the ’20s, when he must have played it.

So, I bought a Mel Bay book and learned some chords. I started backing up my father on the more ragtime numbers like “(Up a) Lazy River” [from 1930], “One of These Days” [from 1910], and songs like that, the ones he used to love to sing.

And then I moved over to guitar. My dad had brought home a guitar a son of his friend had made in shop class, believe it or not, for a project he had done in high school. He was off in the service and hadn’t touched it, so the mom said, “Hey, why don’t you give it to your son, since he loves to play musical instruments?” That was my first guitar, and it had a neck like a tree trunk.

Mettler: You must have gotten all callused up to be able to play that one, then.

McDonald: Yeah, and I think I got some early arthritis just trying to play that thing! (both laugh) A little bit later, my grandmother bought me one of those Danelectro Silvertone guitars from Sears, Roebuck, and I still have one now. I found one in a pawnshop in New Orleans, and it really brought back memories with the amp in the case, and everything.

Mettler: Do you feel guitar and piano are interchangeable for you as a creator? Do those two instruments occupy the same space when you’re creating music or writing songs?

McDonald: As a writer especially, though they are two different mediums. To me, it’s like the difference between a watercolor and an oil. They both produce a certain kind of environment and certain parameters within which to write a song.

In the last few years, I’ve tried to up my game a little bit on guitar. For years, I didn’t even touch the guitar; I just played piano. I still wrote songs on guitar, but usually, I wrote those hoping someone else would record them. I always did like writing on guitar and sometimes on ukulele and banjo, but mostly, I would write on piano.

Mettler: And now we get to see you play guitar onstage again.

McDonald: Yes. For this last record [September 2017’s quite fine Wide Open], we actually worked on songs I had demo’ed while playing them on guitar. That’s how playing guitar live came back into my repertoire. I did play guitar for bands when I was growing up in St. Louis. I probably played more guitar at first than piano. Piano came along later, when we started working up more of an R&B repertoire — like there was on pop records from the late-’60s, the ones that had actual piano on the record.

Mettler: In the early days, you wrote the lyrics first and the music second, but it’s reversed now, right? You switched that process around.

McDonald: It goes either way now; it depends. I have an iPhone full of lyric ideas, and sometimes, that’s the beginning of a song. And sometimes they’re just terrible, and I have to erase them. (MM chuckles)

But more than not in the past, when I was with the Doobies, most of our songs started as musical ideas, and the lyrics came second. But that’s because we were a band and we were often in some room jamming, holed up in a house somewhere in Northern California.

Mettler: So you’d have, say, the musical intro for a Doobie Brothers song like “It Keeps You Runnin’” [from 1976’s Takin’ It to the Streets] before you had the lyrics in your head?

McDonald: Yeah. That’s a song where I had the chord progression laying around, and I would just go ahead and complete the song when the opportunity came to record it with the band.

Some of these songs had other lives, like when I thought I was writing something for a commercial, singing about a vacuum cleaner. (chuckles) But later on, it would become something better — a full song. I did do that kind of commercial writing for a while, like so many composers did, and I sang a lot of background sessions — whatever I could do to pay the bills.

Mettler: And obviously, we hear your voice in the background of so many songs of that ’70s era. Your voice is so distinctive that when we hear you on “Peg” [from Steely Dan’s 1977 masterpiece, Aja] or “Ride Like the Wind” [from 1979’s Christopher Cross], we instantly know that it’s you. You can’t ever say, “Michael sounds like someone else.” It’s always your own vocal identity.

McDonald: Well, thanks; that’s nice to hear. In the era I came up in, it would have been the kiss of death to sound like any other artist who was popular. You know what I mean? It would be like, “Well, we already have a Stevie Wonder. We don’t need this guy imitating Stevie Wonder.” Not that you did it so much consciously, but back then, subconsciously, you were always looking for your own voice — something unique about yourself that you could infuse with all the other influences you might have.

Growing up playing Top 40 music was a really good education for me, because in St. Louis back then — and even in California — to be a popular Top 40 band to get the gigs that were worth getting, the more you could sound like the record, the better. I learned early on as a vocalist that I don’t want to imitate these people, but it was always good to go to school on their phrasing and inflections and learn how to do that so you could do that on the song. In a way, people felt more of a kinship with you when you were performing their favorite song than if you would sing it the way you’d sing it yourself. There’s an arsenal of things you probably couldn’t learn any other way.

Mettler: Was there one early song you sang background on that you felt showed your own identity while you were singing for somebody else, before you jumped out as a frontman in the Doobies universe?

McDonald: That’s a good question. You know, up to that point of joining Steely Dan [as part of their touring band in 1974], I kind of thought of myself as a jack of a lot of trades and a master of none. I thought of myself as a professional musician who liked to play sessions on piano when I could. I was never that good that I was going to be one of the A-list guys, but I would do sessions from time to time. I always felt that, as a songwriter, doing those sessions was also me knocking at the door of giving one of those artists one of my songs. Usually, it never came to much fruition, or if it did, it was never one of their more memorable songs.

But I was always knocking on the door with band stuff in L.A., making the rounds like so many people, and singing backgrounds on so many sessions. When I got into Steely Dan, “Bad Sneakers” [from 1975’s Katy Lied] was one of the first things I cut with them, and I learned something about my voice in the sense of my doing backgrounds. When I sang with myself, there was a certain kind of ethereal quality to doing that that caused a certain kind of phasing and a certain kind of sound that I used, to a great extent, with the Doobies later. There were songs where I realized, “If I do the backgrounds alone on this one, it’ll create that kind of vibe and that sound I learned to do with Steely Dan.” And then Walter [Becker] and Donald [Fagen] would use my voice alone, where I would sing all the parts on “Peg.”

Mettler: Hearing “Michael and Michael” in harmony alone on that song is such a fantastic listening experience, no question.

McDonald: With any singer, when you sing with yourself, it creates a certain kind of phasing quality your voice does with itself that you wouldn’t necessarily be able to do with another human.

Mettler: You’re basically creating your own cathedral effect. We’re surrounded by your own stacked-harmonies identity, all rolled into one.

McDonald: Yeah, and the fact that it’s the same timbre doing all the parts. Especially when you double it, like I was saying before, it creates a kind of weird, ethereal quality to it you don’t get any other way.

Mettler: We all love “Peg,” but my personal favorite Steely Dan background vocal of yours has to be on “Time Out of Mind” [from 1980’s Gaucho].

McDonald: Oh yeah, yeah — that’s a great song. There are so many, and that song is one that’s so wonderful in its own way. But they’re all unique from each other. Those guys in Steely Dan are an enigma in a sense that the music was so strange and beautiful and different, and certainly not anything you would imagine would be Top 40. But they were the darlings of Top 40 for like two or three decades!

Mettler: Right, and with all those crazy time signature and feels, and even the title track to Aja — you can’t even call it anything else.

McDonald: No, it’s true — and I think that speaks to the way, as a record industry, we try to dumb down an audience that’s really capable of appreciating music on a much higher level than it’s typically served. Record companies as a whole have a history of trying to control the product by dumbing it down to something they can produce easily and in great quantity, and more or less try to dictate to people what it is they want to hear. And then a band like Steely Dan comes along, and it proves them wrong.

Mettler: I also think people sometimes forget that in the Doobies, you guys were fooling around with time signatures on many of the records you did together.

McDonald: Yeah, there was a period of time where we were trying to see how many chords we could actually put in one song! (laughs heartily)

Mettler: Which song did you really stack the deck on?

McDonald: Well, “What a Fool Believes” [the No. 1 single from the Doobies’ 1978 album Minute by Minute] is one of those songs that changes keys throughout it — and that’s part of what the personality of the song is, you know? The chorus has a certain kind of lift, and more than any other reason — it’s not that the chords are so unique or anything, but it’s because it’s actually changing keys, and it takes the listeners’ ear to a whole other environment. Those were the kinds of things we messed around with as a band: “What if the chorus moved up to this key?” Typically, when those kinds of things worked, they worked great.

Mettler: Considering that song became a No. 1 single in April 1979, I think it’s safe to say, “mission accomplished.”

McDonald: It’s funny — that whole album [Minute by Minute], I don’t think any of us really were all that confident it was going to become a commercial success. Almost much to our surprise, it was. [Minute by Minute is certified by the RIAA as having sold over 3 million copies.]

Mettler: Bob Ludwig has done a lot of wonderful mastering for your work over the years. Tell me about working with him.

McDonald: Oh, Bob is just fantastic. He’s one of those guys in that field that soars above so many of the rest. There are some great people we’ve worked with in the past, but Bob Ludwig is that kind of go-to guy who understands the whole sonic spectrum so well.

Many times when I’ve mastered a record, it’s really not that much different than when the record is unmastered. It really just feels like it’s been “tidied up,” if you will, in all the frequency ranges. Originally, the whole idea of mastering was that the needle didn’t jump up off the vinyl, and that we’re in that realm where most record players could handle it — the low-end, especially. Then it became an art, like all things in the recording industry and recording production did. And Bob’s one of those guys who, when he masters your record, it’s a lot better than it was before you handed it in. (chuckles)

Mettler: For somebody who needs the character of your vocal to shine upfront on certain songs, or especially before other instrumentation comes in, the quality has to be locked in at that stage, especially when you’re cutting things for higher-grade vinyl.

McDonald: Yeah, I think the overall shimmer and warmth, and all those things a really good mastering engineer can bring to a project that’s been mixed to the best of your ability in the studio — to get it to that stage of mastering where it really comes to life in a way you hadn’t even imagined — I think that’s where the art of someone like a Bob Ludwig becomes obvious.

Mettler: Very much agreed! Okay, the last thing I have to ask you about is something I asked Rick Moranis about almost 15 years ago, and I’m sure you know what it was — that infamous SCTV sketch where he’s playing you, running into a recording studio after getting out of a car just in time to sing the background vocals on [Christopher Cross’] “Ride Like the Wind.” He said to me that he did it out of reverence and that he loved your music. I think you saw that sketch when it actually aired for the first time [at the end of the SCTV Series 4 Cycle 1 episode titled “Moral Majority,” from July 10, 1981]. What did you feel about his homage?

McDonald: Oh, it was hysterical! I was always flattered that SCTV, one of my favorite shows in the world at the time, did that. The moment I actually saw it, I was in a hotel, and I wasn’t in the most, what’s the word for it (slight pause) — I was sideways.

I walked into my room, and I used to leave the TV on, just so people would think there was someone in the room when we were off at the gig. As I walked in, this thing was in progress on the television. I’m looking at it, seeing him [Moranis] in his makeup, driving in his car and hearing him sing on the song, and I go, “Wait a minute, I know that guy!” (chuckles) It took me a second to realize what was going on. It was kind of a spooky moment in a way, because I thought I was having a dream or something.

Many years later, when I was doing the Rock and Soul Revue with Donald [Fagen], playing at Jones Beach [on Long Island, New York], he [Moranis] came backstage. He kind of apologized and said, “You know, I’m really sorry about doing that.” And I said, “Not at all! I’ve probably gotten more mileage out of that than probably anybody else!” (chuckles) My kids have always loved it too. I just found it really flattering.