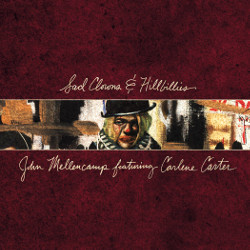

John Mellencamp Explores His American Roots With Sad Clowns & Hillbillies

Rather than succumb to the constant chart-driven pressures of the hitmaking machine, Mellencamp did indeed stand up to reclaim his name in the ensuing decade, establishing himself as one of our most poignant observational songwriters in the process. And his skill at depicting the litany of American tomfoolery and social malaise is once again on pointed display in Sad Clowns & Hillbillies (Republic).

From the double-wide drawl of “Grandview” to the whispery barbed-wire hiss of “Easy Target” to the rootsy country-folk blend of “Sugar Hill Mountain”—one of the album’s featured duets with Carlene Carter—Sad Clowns is a relatively happy amalgamation of fine analog sounds. “We try to keep it as organic as we can,” Mellencamp says of the mix he and veteran engineer David Leonard (1987’s The Lonesome Jubilee, 1993’s Human Wheels) constructed for the album. “We don’t wind it up, and very rarely do we pitch anything. And I’d rather be flat or sharp than pitched.”

From the double-wide drawl of “Grandview” to the whispery barbed-wire hiss of “Easy Target” to the rootsy country-folk blend of “Sugar Hill Mountain”—one of the album’s featured duets with Carlene Carter—Sad Clowns is a relatively happy amalgamation of fine analog sounds. “We try to keep it as organic as we can,” Mellencamp says of the mix he and veteran engineer David Leonard (1987’s The Lonesome Jubilee, 1993’s Human Wheels) constructed for the album. “We don’t wind it up, and very rarely do we pitch anything. And I’d rather be flat or sharp than pitched.”

I recently sat down with Mellencamp, 65, in his New York hotel room to discuss controlling one’s own in-studio destiny, the enduring allure of vinyl, and the secret of how he gets that natural deep “character” in his vocals. Ain’t that America. . .

Mike Mettler: You’ve owned a recording studio—Belmont Mall, in Belmont, Indiana—since the early 1980s. When did you know you wanted to have your own studio?

John Mellencamp: When I would go to those big recording studio complexes in the late ’70s and early ’80s, I would run into a lot of guys with attitudes and egos. I didn’t like that. I mean, yeah, you’ve got to have a certain ego to do what I do, but there’s one guy who’s in charge here—and that’s me. And the truth of the matter is, I’ve always had the best bands. I welcome everybody’s input, but I say things very bluntly.

Mettler: Do you want people to listen to your music on vinyl? Does it still matter to you how they do it?

Mellencamp: I do have a record player, and I get nice turntables and amps to give as gifts to people. But today’s music world is so obtuse to me. I don’t know how the business model works anymore. When we’re mixing these records, we look at each other and we go, “What are we doing? Somebody’s going to be listening to this through earbuds. Maybe we should put some f---ing earbuds in to see what it sounds like!” (both laugh)

Mettler: Well, some of us prefer the hi-res download versions you offer, so we can hear the subtleties and details in the arrangements. That’s more exciting to listen to, I think.

Mellencamp: Yeah, it is, and it’s always exciting to me also. I would listen to records I became very familiar with on vinyl and then repurchase them as CDs, but what I’d find was the warmth was gone. Something was missing.

I remember when the German guy who owned Polygram came to my house in Indiana in the ’80s. He brought a CD with him and said, “I wanted to show you this, because this is the future.” And when he left, I thought, “How is this going to work? You’ve got to get people to buy new machines. Besides, why do we need it? What’s wrong with records?”

And it was an illusion, because people went back and replenished their record collection. Me, I probably have every version of Joni Mitchell’s Blue (1971)—I’ve got it on cassette, 8-track, vinyl, and 50 copies of it on CD. I gave a copy of it to each of my daughters when they were growing up and said, “You have to listen to this record.” And they still love those songs.

Mettler: What other records do you still consider as your talismans?

Mellencamp: [Bob Dylan’s] Highway 61 Revisited (1965), of course. That, and Blue, are probably the biggest ones for me. I still remember Highway 61 from when I was in high school, because there was a skip in “Desolation Row.” And to this day, whenever I hear “Desolation Row,” I wait for that skip.

Mettler: Isn’t that funny? I have the same thing with Cream’s “N.S.U.,” the first song on Fresh Cream (1966). I didn’t even know it actually had a skip until I got the CD where there were a few bars at the beginning of it I had never heard before, since the song never got on the radio.

Mellencamp: (chuckles) “Where’d this come from?” Yeah.

Mettler: You’re the producer on Sad Clowns, and one of the things I like is it has a very distinct stereo soundfield. Some things are very much in the left channel, and some things are very much in the right channel.

Mellencamp: (nods) It’s very old school. And I have the best engineer, Dave Leonard. When I was working with T Bone [Burnett, on 2008’s Life Death Love and Freedom, and 2010’s No Better Than This], I loved his engineer [Mike Piersante]. When I was talking with him, I said, “Mike, where’d you learn how to do all this?” And he went, “Oh, from Dave Leonard. I was his apprentice.” I went, “Dave Leonard?? He did Lonesome Jubilee!” When I quit working with T Bone, I went and called Leonard to get him back because I love him, and he and I have always gotten along.

Mettler: Did you and Dave have a discussion about the sound template for Sad Clowns before you started recording?

Mellencamp: We have a way of working. We don’t plan anything, but we go, “Let’s have a surprise. Let’s see which way the music goes, and then let’s figure out how to mix it so that it all makes sense.”

We never said, “This is how it’s going to be.” The only record I did that with was Lonesome Jubilee: “This is how it’s going to be, and these are the instruments we’re going to use.” So people had to go learn how to play those instruments.

Mettler: I like hearing singers be honest, and be who they are at whatever age they are. When “Easy Target” came out a few months ahead of the record, I was a bit put off by people comparing your vocals on it to Tom Waits and Leonard Cohen.

Mellencamp: And that’s bullsh--. The reason my voice sounds the way it sounds is (slight pause)—it’s because I smoke. There’s nothing that I’m “putting on,” or “trying to do”—it’s because I’ve smoked my entire life! Listen, I’ve been smoking for 50-f---ing years. What do you think is going to happen?

It pisses me off. If you want to make a comparison, compare me to Louis Armstrong, because that’s what it sounds like. That’s where it all came from. He was a smoker. It just happens to your voice. When people say, “He’s doing his Tom Waits,” it’s indicating I’m putting it on. I’m not putting anything on. Really, that’s just lazy writing.

Mettler: My response when people say stuff like that is, “No—he’s doing John Mellencamp.” This is the artist. If you want to describe the artist, you use his name. That’s who he is. His name defines who he is.

Mellencamp: Right. Not something derivative. But don’t forget—I was brought up listening to Woody Guthrie, Ella Fitzgerald. My dad’s only 20 years older than me, so he was a kid raising kids. They played their music, which was the precursor to our music.

Mettler: Was Frank Sinatra in that mix too?

Mellencamp: Yeah, a little bit. My parents had Odetta records, Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger. One of my favorite records was by Burl Ives. I loved Burl Ives and that big, booming voice of his. Funny thing is, I stole a line right out of a Burl Ives song, and nobody knew it! I wrote a song for Meg [Ryan’s] movie [2015’s Ithaca] that Carleen Carter sings on this record. The line is something like [speak-sings], “Sugar Hill, Sugar Hill Mountain, where’s there’s bubblegum and cigarette trees”—and that’s straight from a Burl Ives song! (chuckles) Well, I don’t think it was “bubblegum,” but it was “cigarette trees.” So I thought, “Yeah, I’ll use that!”

[The line comes from “Big Rock Candy Mountain,” a song written by Harry McClintock in 1928, and covered by Ives circa the 1950s/early 1960s, and it goes: “On the birds and the bees/And the cigarette trees.”]

Mettler: Speaking of The Lonesome Jubilee, there are those who feel you essentially created the alt-country movement with that 1987 album.

Mellencamp: We were just doing what we do. I did an interview with somebody recently who said, “Now that you’re leaning country,” and I said, “Whoa. I’m not ‘leaning country.’ I was f---ing doing this before these guys were born. Country has finally caught up to me.” I hate to sound like Little Richard in an interview, but I was doing it before those guys.

Mettler: What’s that one line you wrote many years ago: “Five years ahead of their time or 25 behind”?

Mellencamp: How do you know that line? That’s from a really f---ing old song!

Mettler: Yeah, it’s from “The Great Midwest” [a song on 1979’s John Cougar].

Mellencamp: Yeah! I don’t even know what I was talking about when I wrote that. . . (both chuckle)

Mettler: You could say you wrote that song 30-40 years ahead of its time, literally. I think it would be interesting to hear you sing it now with the voice you have today, and the. . .

Mellencamp: . . .gravitas? Yeah. I’ve never even considered doing that song. Never dawned on me.

Mettler: Well, keep it in mind. How do artists even get started now? If Woody Guthrie started today, he’d be in a coffeehouse somewhere playing to ten people.

Mellencamp: That’s it. You’re exactly right. Music has morphed into, “(How Much Is) That Doggie in the Window?” That’s what created rock & roll—Patti Page singing, “(How Much Is) That Doggie in the Window?” [in 1953]. I mean, can you imagine: “Mary Had a Little Lamb” was actually a hit record. Can you imagine someone going, “Have you heard that song, ‘Mary Had a Little Lamb’? F--ing great!” Did that really happen? (cackles)

Mettler: That music was of a certain era. And like you said the other night, rock & roll had a 50-year window, and now we’re in some kind of post-rock era that I’m not sure actually has a name yet.

Mellencamp: I just read an interview with Ray Davies where he said, “Yes, I believe rock & roll will come back.” I almost called him up and said, “Ray, it’s not coming back. It’s dying out.”

Mettler: As an artist, you just have to keep doing what you want to do, and if x number of people find it, fine. If not, you keep doing it anyway.

Mellencamp: That’s exactly right. And I’m still fortunate enough that I can go out and tour if I want to. That’s what I do. But I’m in the third act here. I hope to really concentrate on what I started to do in the third act—paint and make things, rather than concentrate so much on music.

But every now and then, I’ll sit down and write a song and then go paint, and I’ll forget I even wrote the song—which is what happened with “Easy Target.” When you’re always making art, it’s like you look in the closet and go, “I forgot I even had this.” Same thing, in my case. It’s an intellectual discovery: “Oh! When did I write this? It’s good!”

I’m very lucky. I live the way I want to live and do what I want to do, and if people don’t like it, tough sh--. And that’s it.