In the Court of Ian McDonald

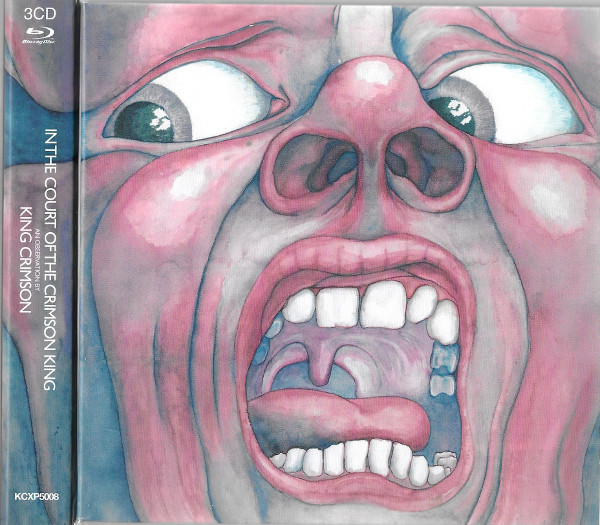

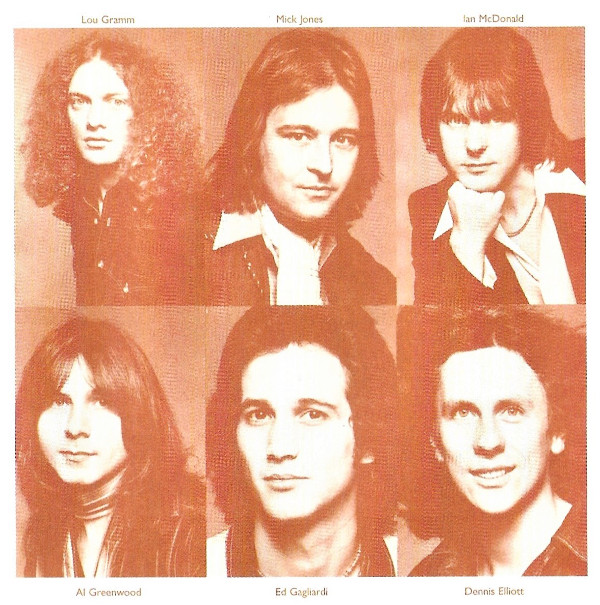

First, his flute, clarinet, and organ work on “I Talk to the Wind” lends a particularly seductive wispy character to one of the most magical, mystical songs on King Crimson’s groundbreaking October 1969 debut, In the Court of the Crimson King. Cut to almost a decade later, where his layered baritone saxophone lines are the lynchpin driver of “Long, Long Way From Home,” one of the many hard-charging hits found on Foreigner’s self-titled multiplatinum March 1977 debut album.

“I’m quite proud of the fact that the two bands I was a founding member of, King Crimson and Foreigner, are still out there playing,” McDonald admits. Indeed, the current seven-man incarnation of Crimson just wrapped a 50th anniversary tour in late 2019, while Foreigner has been doing a series of 40th anniversary album-oriented shows interspersed throughout their regular touring schedule that have often included the likes of McDonald and original vocalist Lou Gramm. “I know what my contributions to those songs were, so I’m happy to be doing them again,” he adds. “And it’s great to be onstage with as many of the original members who are still around. It’s always fun to do that. The audiences have been great, and that makes all the difference.”

Recently, McDonald’s current passion project has been as a key member, co-writer, and producer of Honey West, a guitar-driven band that showcases the centered, focused muse of frontman/lyricist/lead guitarist Ted Zurkowski. Though the CD and digital versions of their debut album Bad Old World came out in May 2017, it took McDonald and company more than two years to get to a point where they were comfortable enough to release it on high-grade 180-gram vinyl via Readout Records, as mastered by Ryan Smith at Sterling Sound in New York.

Recently, McDonald’s current passion project has been as a key member, co-writer, and producer of Honey West, a guitar-driven band that showcases the centered, focused muse of frontman/lyricist/lead guitarist Ted Zurkowski. Though the CD and digital versions of their debut album Bad Old World came out in May 2017, it took McDonald and company more than two years to get to a point where they were comfortable enough to release it on high-grade 180-gram vinyl via Readout Records, as mastered by Ryan Smith at Sterling Sound in New York.

That level of unbending precision turned out to be quite the wise decision, for the character of McDonald’s flute break in “Brand New Car,” the garage-rock jangle of “Generationless Man,” and the cool echo effect deployed on the album closer “Dementia” are best realized on vinyl. One could even say that a certain second-generation rocker/producer who knows a thing or two about catchy song construction and goes by the name of Dave Edmunds would surely be proud of just how well the latter two tracks come across on wax.

“Well, if I’ve done something that would please Dave Edmunds, then my work is done,” McDonald replies with a hearty laugh.

McDonald, 73, called in from his homebase in New York to discuss the painstaking journey he undertook to get Bad Old World onto vinyl, his ever-wary reaction whenever he hears about original releases being remixed for anniversary collections, and the importance of having air present in whatever he plays. I’ve been here and I’ve been there and I’ve been in between. . .

Mike Mettler: I’m glad to see that a lot of the material your handiwork is featured on has been reissued on 180-gram vinyl.

Ian McDonald: Well, that’s what we did with the Honey West LP. We wanted to be sure it was good-quality vinyl — but it took a while, because we had to go through a number of different manufacturers until we were happy with the test pressing and could give it the go-ahead. That’s the reason there was a bit of a time-lapse between the CD and the vinyl release, because we wanted to make sure we had really good-quality, good-sounding, heavy, 180-gram vinyl.

We had some trouble with the test pressings, and I wasn’t going to let it go out if we weren’t happy with it. But we’re happy with the result now, and I think it was worth the wait.

|

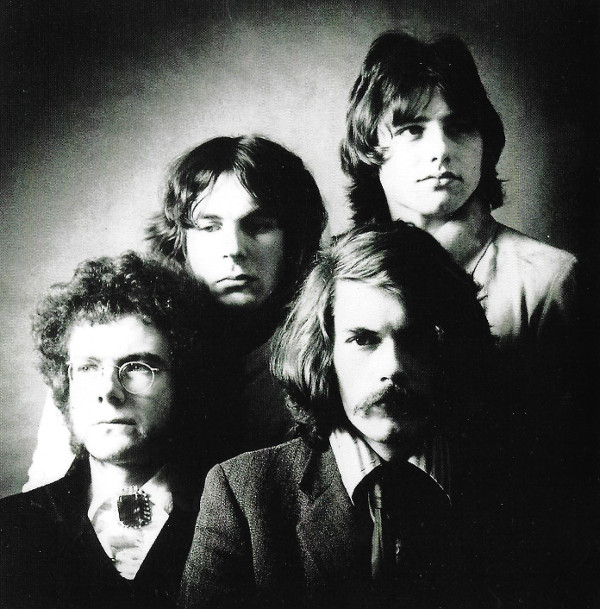

Ian McDonald in 1969 with King Crimson. Photo by Willie Christie |

Mettler: It was literally worth it, you mean, in terms of both the wait, and the weight.

McDonald: Yes, that’s right, and it is nice and heavy as far the weight is concerned, yeah. (chuckles)

Mettler: When you were doing the QC, was there one thing you heard where you went, “Okay, now we’ve got it right”? Any particular songs or sounds that helped you feel the LP was at the point where you could finally approve it?

McDonald: It was actually more about the physical property of the disk. There was some warping and some of the grooves were not centered, so the stylus would go back and forth, or left and right, a little bit, and that would cause some “wow”ing [i.e., a variation in pitch per each single revolution of the LP]. And there were also some little divots in some of the tracks, if you looked at them closely. These were the kinds of problems we had that I couldn’t approve.

Mettler: This LP is a representation of some of your most important life’s work, after all, so it’s totally understandable to go for that standard.

McDonald: Yes, that’s the kind of thing we were getting after. But we’re past that, and we’ve got the real thing now.

Mettler: Is there one or two vinyl records from years past, either ones you grew up with or listened to over the years, that have stood up as benchmarks for you?

McDonald: Oh my goodness! Let me see now. (slight pause) I’m trying to think back to when I still lived in London. I remember when The Beatles’ Abbey Road album came out [in September 1969], I listened to Side 1 and Side 2 over and over and over again, all day long. I thought that was amazing.

And there was a record I used to listen to a lot by an alto sax player by the name of John Handy, who was quite an influence on my saxophone playing at the time. It was called Recorded Live at Monterey Jazz Festival, and there were two tunes on it — one on Side 1, “Spanish Lady,” and the other one on Side 2, “If Only We Knew.” Each track was basically 20 minutes long. That was something I listened to many, many times. That was a favorite of mine.

[Live at Monterey Jazz Festival was recorded on September 18, 1965 and originally released on LP by Columbia in 1966, and later on CD by KOCH in 1996.]

Mettler: The specific choices you made for how the Honey West record sounds on vinyl are the kinds of things our audience loves, by the way.

McDonald: Well, I like to have that sense of air in the tracks, so that you’re actually having a sense of the vibrations traveling from a musical instrument or a voice. It’s one of the reasons why I always put an acoustic guitar on pretty much every track on the Honey West album. Whether you can hear it or not, an acoustic is in there with all the electrics because, to me, that sense of wood and air and strings vibrating — it adds something to the pure electric guitars. Even if it’s not all that apparent, it’s in there.

Mettler: Speaking of guitars, you have a nice stereo moment at the beginning of the opening track “The September Issue,” with the way those guitars pan left and right.

McDonald: And that was done live, you know. The lead guitar, the solo one that’s doing the ad-libs — that was all done live in the studio. That’s not an overdub. The two guitars were live, all the way through the song. That’s me playing the solo live in the studio and not redoing anything, with Ted [Zurkowski] on rhythm guitar on one side, and me on lead guitar on the other. I think I’m in the right channel. I did all the lead guitar on the album, as well as some of the rhythm tracks. The Honey West album is essentially live in the studio, with my production additions around it.

Mettler: I think it’s fair to say it’s no accident that some of your instrumental work on the Honey West album makes us think of King Crimson’s “I Talk to the Wind,” all these 50-ish years later. (McDonald chuckles) [In the Court of the Crimson King was initially released on October 10, 1969.] The surround sound version of that track, as done by Steven Wilson, is just something to sit in the middle of, enjoy, and take in. It’s really an amazing experience, I have to say.

McDonald: Oddly enough, there was no acoustic guitar on that track, and I always wished I’d put an acoustic guitar on there. The song was written by me on acoustic guitar, but an acoustic never made it to the recorded track, unfortunately. And because I didn’t play guitar at all on the In the Court of the Crimson King album, sometimes, people are surprised that I do play guitar. Songs like “The Court of the Crimson King” and “I Talk to the Wind” were actually composed on guitar, but (chuckles) I don’t have a guitar credit on the album since I didn’t play guitar on the album!

Mettler: You have released demo versions of you playing that material on guitar, of course.

McDonald: Oh yes. There’s a record called The Brondesbury Tapes, which are all demos of the pre-Crimson songs. [These 1968 demos, credited under the pre-Crimson band name Giles, Giles and Fripp, were released on CD in 2001.]

Mettler: Right. I also remember the alternate version of “I Talk to the Wind” that Judy Dyble [of Fairport Convention] sang on that’s on A Young Person’s Guide to King Crimson [released in March 1976].

McDonald: That’s on The Brondesbury Tapes as well, yeah. Again, I haven’t heard the surround sound version. I get very nervous whenever I hear about any remixes of things like that, because I was there in the beginning.

Mettler: I can understand that. I’m okay with these mixes because your compatriot Robert Fripp is quite meticulous in his own way, and he had to tacitly approve anything when it came to mixing the whole Crimson catalog in surround. Steven did most of the early ones, and Jakko Jakszyk [whom McDonald has played alongside with other past and present KC members in the 21st Century Schizoid Band] has done some of the later ones. As Steven told me directly, if Fripp didn’t like any of the surround mixes for any reason, none of it would have even been released at all. The right guys, working in the right context, did it in the right way. So, I think you can rest a little bit in terms of it being done properly.

McDonald: Well, there were things I did when we were mixing it [Court] on the mixing console that may not be all that apparent, and that’s where I get a little bit nervous whenever somebody takes the multi-track — and it was only eight-track, by the way — and remixes it.

On “Epitaph,” for instance, there were two tracks of Mellotron on that song, and I kept the volume of the two tracks moving all the time, very subtly, up and down against each other. Again, it’s not really all that apparent, but it’s there. You do get a sense of motion on the sustained chords on the Mellotron, because they can just sound rather flat sonically without doing that. I hope I’m describing it properly, but that’s one of the things we did when we first mixed the album, and I hope Steven Wilson was aware of all that when he did his mixing.

Mettler: I’d like to think so. The liner notes for the 3CD/1BD 50th anniversary edition are pretty detailed in describing what was done production-wise, and they do include things like just the backing track of “Epitaph” and one of the “Wind Sessions” of you just doing your thing, all on its own. And there are some alternate takes like a version of “Wind” where it’s just you and Robert together and nothing else with it, with different solos. It’s basically, “Here’s everything we’ve got, and you can figure out which one appeals to you the most.” Me, I like hearing all of it, because I like hearing the evolution of what I consider to be a signature track of yours.

McDonald: Yeah, well, I tend not to like that kind of thing. But that’s just me. I’m very picky about stuff like that. (chuckles)

Mettler: I can see that, but like I said, I still like hearing it all myself. (chuckles)

McDonald: Another thing is, I do know that on the 50th anniversary tour, they did go back to the first [original] version of Crimson King material. When I saw them live, they did four tunes from that album, and the way the players learned the parts, they were given copies of the individual tracks of each song to learn and emulate. And that’s one reason the current touring version of Crimson sounds so good when they play those original tunes, in my opinion — especially “Epitaph,” which I thought was fantastic when I saw them here in New York.

Mettler: I totally agree. I saw them in Toronto on the 50th anniversary tour at the end of this past summer [at Budweiser Stage on September 14, 2019], and I also saw them quite a few times at the one mid-size theater in Times Square that always seemed to keep changing its name. [The PlayStation Theater, formerly known as Best Buy Theater and Nokia Theatre before that, recently closed its doors on December 31, 2019 following the expiration of its lease.]

McDonald: You’re right, it did. I saw them at the Beacon Theatre here myself, a few years ago [in November 2017].

Mettler: If you don’t mind me mentioning Foreigner here, I have to give you a nod for “Tramontane,” the great instrumental on [June 1978’s] Double Vision. That’s mostly your handiwork, yes?

McDonald: I have a co-write on that [with keyboardist Al Greenwood and guitarist Mick Jones], and the melody I’m playing is on what’s called the Lyricon, which is like an electronic clarinet. It’s played like a wind instrument, but there’s no air going through it. It’s all done with the air pressure. [It’s also known as a “wind synthesizer controller.”] You may find that Tom Scott played the Lyricon on some of the Steely Dan albums.

[MM notes: Scott did indeed play the Lyricon on three SD songs total — specifically, on “Peg,” from September 1977’s Aja, in addition to both “Glamour Profession” and “My Rival,” from November 1980’s Gaucho.]

Mettler: Now that you’ve done vinyl for Honey West, any thought of doing vinyl for your solo album Drivers Eyes, which came out in 1999?

McDonald: (chuckles) I would if I could find the master tapes, which I lost. Some of the multitracks got lost. I mean, I think I have the two-track masters which, now that you mention it, I could make a vinyl version of that. But unfortunately, I lost about four tunes on multitracks. I don’t know what happened. But I’ve always wanted to remix the whole album. And it would be in stereo. I’m not a mono freak.