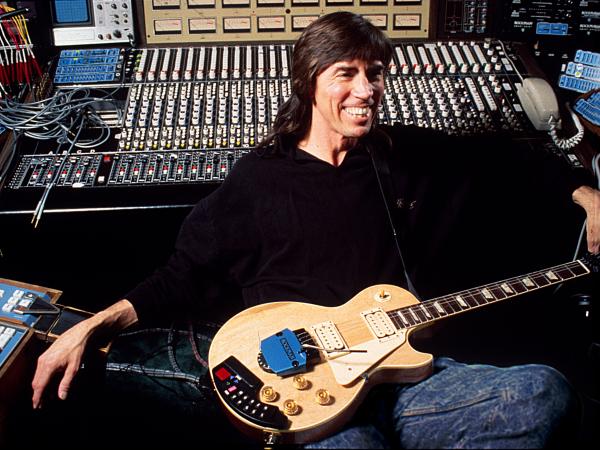

Boston Analog King Tom Scholz

Here, Scholz, 66, and I discuss how he felt the need to recast certain songs for Life and why he thinks analog will always trump digital. “The whole purpose of making music to me is the emotion,” Scholz emphasizes. “That’s why I do it. It gives me a feeling of awe or something else that can only come from music. That’s my whole point for doing it for me, for our fans, and for any listener: Creating an emotion to respond to.” One might even say it’s more than a feeling.

Mike Mettler: You’ve reclaimed three songs on Life, Love & Hope from the last Boston album, Corporate America — and made them sound better in the process. How did you do it?

Tom Scholz: I put those songs on there because I didn’t feel I captured what I was looking for with that release. It’s probably most obvious if you listen to “You Gave Up on Love (2.0)” on this record as opposed to the version on Corporate America. It’s almost like two different bands, even though a lot of the tracks are the same. Whatever was going on back then wasn’t working. So it was completely re-recorded, and I finally got what I was looking for.

The only song from Corporate America that I put on Life that was largely unchanged was the second cut, “Didn’t Mean to Fall in Love.” The production is a little bit better, but the reason I put it on was it was co-written with Curly Smith and a friend of his [Janet Minto], and I just didn’t think it got a fair shot at the light of day on Corporate America, and I wanted to give it another chance at life. [laughs]

Mettler: We’ve talked before about how much disdain you have for the digital realm. What gets lost there? What’s missing?

Scholz: First, let me say this: With analog sounds, I can’t tell the difference between the actual performance and the analog playback. When I’m running the 2-inch tape or the mixdown tape and I switch between input and monitor in my studio [Hideaway Studios II], I can’t tell you which is the real one. The realism is the main thing.

Technically speaking, there are three things wrong with digital. First, the resolution — the measurement they have to make on the waveform — is not nearly accurate enough for the low volume information on the record. Second, the sample rate is ridiculously low. You can’t hope to sample a 15-kHz high-frequency sound at 44k at less than three times the waveform and expect to duplicate it. Even a 10-kHz tone, such as when a singer sings an “s” sound, or when a cymbal is playing, or you have a guitar with a lot of distortion — the high frequency is just destroyed. And it’s not destroyed in a nice way, with distortion overloading or tape saturation or some nice harmonic thing; it’s a completely alien sort of unnatural form of distortion. The sample rate is way too low.

And the third thing is for whatever reason they haven’t been able to make a waveform that doesn’t have phase-angle distortion. I remember back in the origins of the digital age with 3M making their horribly expensive and horrible sounding multitrack digital recorder that was going to replace their 2-inch M79 tape deck. And one of the criticisms from technical people was, “What about the phase-angle distortion?” And they said, “Well, the human ear doesn’t hear phasing.” How arrogant can you possibly be? The way we locate sounds is the relative phase of the high and low frequencies!

This is what destroys the depth of music and good production. To me, digital always sounds like it’s played through a flat plane in front of you. Now, a good analog recording played through a good pair of speakers sounds like you’re listening to things happening in a big hall. You can hear things happening far away, and things happening close up. Digital music is all on a flat plane, and I think that’s because of the phase-angle distortion.

Those are the technical issues. Now I’ll add this, from the nontechnical point of view — digital just sounds crappy. [both laugh] I just can’t listen to it for very long.

Mettler: Let me further bend your professorial ear. Why is vinyl the better way to hear music?

Scholz: Vinyl is better simply because it is a better analog reproduction of the original. The waveform is virtually exact. But there are limitations with vinyl. The absolute best way to listen to music is on a high-quality reel-to-reel audio tape. Unfortunately, that option went by the wayside when the CD, that new wonderful thing, came out, which is a good example of major corporations selling people a bill of goods. I remember hearing, “But CDs won’t wear out. And they won’t skip.” [laughs heartily]

The scary thing is if you look at a digital waveform for a CD and you look at one of the quiet segments of a piece of music, and if you blow it up to see what’s being reproduced — it doesn’t even look like music. It’s just these horrific, rectangular representations that used to be a nice waveform. There’s just nothing left.

Mettler: I liken listening to Life, Love & Hope to unpeeling an artichoke and finding all of the layers within. And that’s also part of the joy of listening to a record more than once all the way through, by the way.

Scholz: I always felt that listening to a Boston record is like watching a movie you really like again and again. You find all these weird little things that you may not have gotten the first time. That’s how I always felt with these productions, because I put an awful lot into them. A traditional pop song has three choruses that are all identical, and they could have been done once and then flown into the mix. That never happens on a Boston recording. They’re always different because I just have so many ideas, and I like the chance to use as many of them as possible. For example, a bass line will be one thing on the first chorus and then it will be something different on the second because I have a lot of ideas about the way it should be played.

Mettler: That might hearken back to you tapping into all of the classical music you listened to growing up and absorbing nuances like orchestral sweeps and different movements.

Scholz: Yes, it’s repetition of a theme, with variation. That’s what makes what I do worth listening to more than once, doesn’t it?

Note: An extended version of this interview can be found on Mike Mettler’s own website, soundbard.com.