Arlo Guthrie Gives Thanks for 50 Years of “Alice’s Restaurant Massacree”

Here in 2017, we gladly fete 50 years of the release of “Alice’s Restaurant Massacree” on Guthrie’s October 1967 debut album, Alice’s Restaurant, and 52 years of the song’s initial inspiration, the “meal/litterbug incident/draft refusal” in question itself. BTW, I think some people may not even realize the third word in the song title is “Massacree” with two e’s at the end, not just one, and that it has additional meaning related to the concept of delineating an improbable situation, rather than referring to some kind of outright slaughter. (You’ll know exactly what I mean once you cue it back up.)

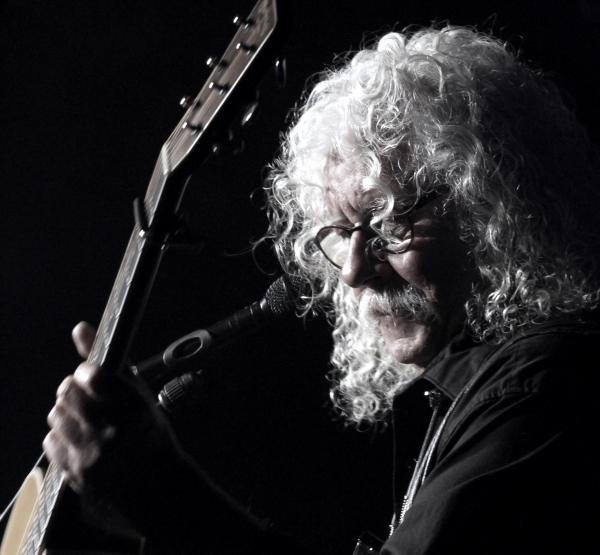

To carve the song up with the respect it deserves, Guthrie, 70, and I recently got together to give thanks and break bread in the virtual sense to discuss the song’s sonic origins, what had to be done to ensure it fit perfectly onto one album side, and the Guthrie family’s storied holiday tradition of playing Carnegie Hall in New York, which occurs this year on November 25. As you’ll soon see, you can get anything you want — just ask Alice. . .

Mike Mettler: How does it feel to be the author of a song that has literally taken on a life of its own, having garnered such deep-rooted meaning for so many families’ longstanding holiday traditions? Something you never could have predicted at the time, I’m sure.

Arlo Guthrie: I love being associated with an American holiday! Naturally, it was totally unforeseen in the early days. Over the years and decades, I’ve been surprised by many things, but hearing of people who can actually do the entire song was the most surprising thing of all. As you say, it has a life of its own at this point.

Mettler: As a wordsmith etymologist at heart, one thing I find interesting is the song is often referred to as just “Alice’s Restaurant” rather than by its full title. Maybe that stems from the one-word-shorter album title, and/or how you refer to it in the first line? Did the song always have a three-word title as you were working on the lyrics initially, or did that morph as you were creating its overall template?

Guthrie: My father [folk legend Woody Guthrie] loved playing with words, both spoken and written. I think I inherited some part of that love. Initially, I didn’t even call the song “Alice’s Restaurant,” but called it “The Massacree” instead. That changed when the record and then the movie became available. [As mentioned above, the album Alice’s Restaurant was released in October 1967, while the film of the same name, starring Guthrie and directed by Arthur Penn, came out in August 1969.]

Mettler: Was it always going to be mostly spoken/narrated rather than sung the whole way through?

Guthrie: I remember when I was writing a screenplay based on one of his novels, Seeds of Man, I wanted to keep his dialogues and descriptions as he had written them. The way the characters spoke was informative as to who they were. Then I ran the script through a spellchecker, and it would stop at every sentence, trying to correct me. I realized it was a useless task. When I hear my own voice singing and speaking on the original recording, it’s like listening to a different person.

Mettler: “Alice’s Restaurant Massacree” takes up the entire first side of your 1967 debut album. As you were recording it, did you have to be mindful of its actual length in terms of how much music would be able to fit on one side of a vinyl record?

Guthrie: I had written a performed the song about a year or two before the recording, and would not have believed that anyone would want to make a real record of it. So, I was not mindful with regards to the limits of technology at the time.

Mettler: Was there a specific sound template you plotted for how you wanted the song to come across on wax, something you mapped out with producer Fred Hellerman? Did you also have to watch the sound level of the audience laughter and those few instances of coughing that occur all throughout the song?

Guthrie: The only thing I didn’t like about the recording was that we had recorded it live in a studio with an invited audience, all of whom had heard the song many times. The consequence of that was that although the audience was enjoying it, they weren’t laughing where new “victims” would have laughed. Fred Hellerman was able to minimize the problem, but it was hell to perform it.

Mettler: Did you have to cut anything from the song to fit that 18-minute side length, either in terms of the lyrics or any of music laid down for it on the accompanying multitracks? Am I right in assuming it was a live 2-track recording, by the way?

Guthrie: It was probably recorded in stereo, which was entirely new at the time. In fact, Warner Bros. made both mono and stereo records, which was before anyone had the use of 4-track machines.

Mettler: Speaking of vinyl, is that your personally preferred medium for listening to music?

Guthrie: I always love vinyl, as it had developed over 100 years and sounded really good. I was and remain skeptical of digital recordings, but for most people, on most platforms, there’s not any noticeable difference.

I still love recording on tape and transferring to the digital format, although we’ve recorded digitally too. There are all kinds of ways to make the digital sound something like tape, and we’ve tried them all at one point or another. It’s a work in progress.

Mettler: On the song, you deploy the Piedmont fingerstyle on your acoustic guitar, which hearkens back to the tenets of an African six-string style. Why did that choice fit the song’s mood and tone? Did it stem from you having heard and seen folks like Pete Seeger, Mississippi John Hurt, and Doc Watson perform in that style, or was it a combination of all of them?

Guthrie: I’ve been a lover of the American musical experience since I was a little kid. My first love was ragtime, and at some point early on, I learned how to emulate that style on the guitar — essentially, a walking bass with a melody on top. When I figured out how to do that, I immediately transferred all the ragtime pieces I knew on piano to the guitar.

Pete was quite capable as a fingerpicker, but the real masters were guys like Doc and John Hurt. I didn’t miss a show either of them did if I was anywhere within 100 miles. John Hurt was so freaking smooth and graceful in his playing, and Doc was a stickler for hearing every note clearly. Ramblin’ Jack Elliott was the first guy I heard play that style, and he’s still doing it today.

Mettler: He sure is. What’s the year, make, and model of the guitar you played on the song originally?

Guthrie: I had a Martin D18 that my father bought for me at some point while I was in high school. I had the instrument modified by Porfireo Delgado in Los Angeles. I played it until the early 1980s. It still hanging on the wall here [at home].

Mettler: I know you haven’t played the song live much at all over the years, but when you do, you’ve modified some of “Alice’s” lyrics in those subsequent performances in the ensuing decades.

Guthrie: I’ve only performed “Alice” once in a while, usually during some 10th anniversary tour — and the next one comes next year. I realized there were younger people coming to the shows who had no idea that there had been a war in Vietnam, let alone what a draft was. So, I had to explain some of those kinds of things in order for the song to make sense. Otherwise, I’ve kept it pretty close to the original lately.

Mettler: Do you consider that to be a part of the overall folk/songwriter tradition — to comment on the signs of the times in real time, theorize about the evolution and/or devolution of our societal mores, etc.? Do you consider that to be your primary role as a songwriter and artist?

Guthrie: Folk music for me is the original social media. And just like people comment on things going on these days through the social media we now use, I’ve added my 2 cents’ where I thought appropriate.

Mettler: It’s interesting how many Woody Guthrie songs feel as relevant today as they did when they were initially written and performed. If your father were still here with us on this mortal plane, how do you feel he would have responded to the state of the union today?

Guthrie: One of the best things my father did in songs and books was to give his audience a sense of destiny and purpose. He wrote about a better world for everybody, not just those with power or authority. He had a vision of a world that overcame the prejudices and bigotry of the past, where there was enough for everyone, and where everybody counted. He passed that vision on to many others, me included. In this family, we take those ideas pretty seriously.

Mettler: Speaking of your family, do you feel you have a special, intuitive/DNA-rooted performance connection with Sarah Lee and Abe, and Cathy and Annie, when you’re all onstage in various incarnations together and how you all harmonize up there?

Guthrie: Each of our kids has a very different musical style and comfort zone. But we also know how to keep it basic enough so we can do those styles together. Personally, I love just being a part of the band sometimes, and not having to be in the spotlight.

Mettler: Do you feel a special/unique connection with Carnegie Hall itself, where the family will be playing your Re:Generation Tour gig on November 25? You’ve performed there, what, 55 times now to date? What is it about that locale that makes it so special?

Guthrie: Carnegie Hall has become a tradition for our family. I began playing there before any of them were born. And my wife Jackie and I loved going every year for the last 50 years or so. It took me a few years not to be intimidated by the place, but these days, it feels like coming home. There are so many wonderful memories of the times and the people I’ve played with. It’s too much to think about, so I just go and do it.

Mettler: By my calculations, your next round of performing “Alice’s Restaurant Massacree” somewhat regularly would be set for 2027 and maybe into 2028, in honor of the song’s 60th anniversary. Do you already have a plan for that tour? We do expect you to still be with us all then, of course.

Guthrie: If I’m still around, we’ll be doing a celebration of the 50th year since the movie was released [which would be in 2019]. That tour will start sometime next year and run for 2 years. At least that’s the plan.

Mettler: Finally, we’re also soon approaching the 50th anniversary of Woodstock [in August 2019], so I hope you don’t mind if I ask your opinion about the ongoing impact, or lack thereof, of that festival. What does Woodstock mean to you today?

Guthrie: Imagine what would happen if an insurance company announced that for the safety and well-being of their clients, fees would be waived for a year. The world would be astounded. But, that’s exactly what the promoters of The Woodstock Festival did. And I think that’s why we’re still talking about it. It set an example of human decency, even at the expense of making a fortune. We could use some of that these days.

- Log in or register to post comments