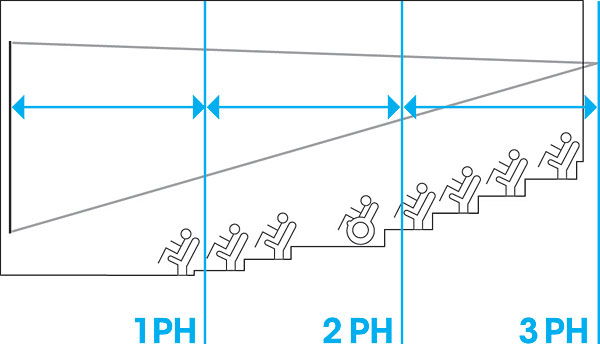

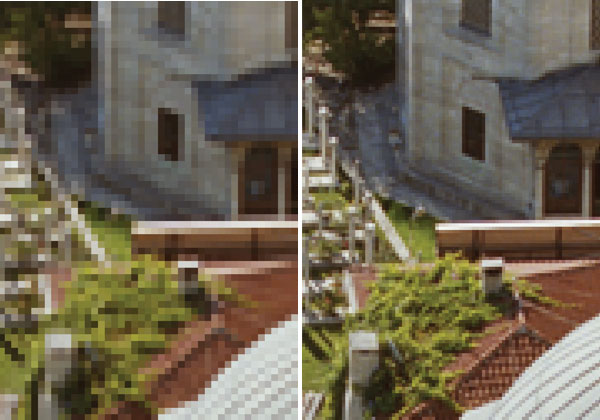

IFS agrees : The resolution is the 4th aspect of picture quality, behind contrast, color saturation and color accuracy. 4k may be useless in displays of 70'' or less. I remember 3 years ago saw a 50'' 720p kuro display looks much better than 1080p LCD of the same size from 10Ft because the contrast was better in the PDF. But you have the room for a 100'' display (and the money) , then those extra pixels gonna make the big deal.... Right now I see the 3D with more future in the mass market.

Ps: congratulations to the staff of HT mag excellent work . Atte. A friend from spain.