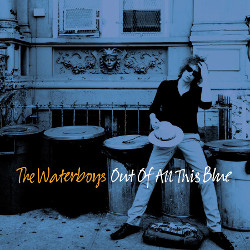

The Waterboys’ Mike Scott Pours a New Sound Palette for ‘Out of All This Blue’

“I purchased a whole load of hip-hop plug-in tools from these big libraries I found online,” the Scottish-born Scott revealed. “One was called Strictly Hip Hop [by E Lab], and Hip Hop Militia [by Prime Loops] was another one I enjoyed quite a lot. These are loops I could fit into any tempo, and they’d all sound great. I could manipulate the sound quite a bit that way, and even make combinations of loops that would only take up just a half-bar. There was a lot of room for my own creativity.”

Rather than replacing his penchant for guitar-driven melody, Scott’s plug-in usage only served to enhance the sound palette for Blue songs like the spoken-word reverie of “Santa Fe” and the rowdy tone of “The Hammerhead Bar.” To further dissect the ins and outs of Blue, Scott, 58, and I got on the line to discuss the album’s initial inspiration, the many intriguing ways he constructed the song arrangements, and what Bob Dylan’s favorite Waterboys song is (and why).

Mike Mettler: From what I understand, Curtis Mayfield had something to do with the impetus behind Out of All This Blue, which had stemmed from you randomly stopping off at a pop-up record store in New York.

Mike Scott: He was a big influence on this record, yes. I was in New York in 2012, working with my fiddler, Steve [Wickham]. It was a late summer night, and there was a storm. We ran out and made a stop in a pop-up record store called Tropicalia in Furs on East 6th Street [in the East Village]. They were playing a fantastic record that had a slick, funky, slightly uptempo groove with a voice that sounded slightly familiar, and beautiful, crystal-clear string arrangements. I asked the dude [working there] what it was, and he said it was [1971’s] Roots, by Curtis Mayfield. And I thought, “Well, of course it’s Curtis!”

I had never heard that album before, and I bought it on the spot. That combination of melody, groove, and sophistication became my ambition and my watchwords for this record.

Mettler: One of my favorite songs on the album is “Morning Came Too Soon,” which is 8 minutes long. How did you put that one together?

Mettler: One of my favorite songs on the album is “Morning Came Too Soon,” which is 8 minutes long. How did you put that one together?

Scott: Well, it began as an acoustic song. I wasn’t happy with the tune, so I started developing some more jazzy chords for it. I wanted something uptempo underneath it, and I went for that classic doubled-up snare rhythm certain mid-period Motown songs had, like [1967’s] “Reach Out I’ll Be There” and [1965’s] “I Can’t Help Myself” [both by The Four Tops].

I chose two loops. There’s one in each speaker, and I also programmed in a lot of fills I selected from those plug-in collections. I was quite judicious with them, and I spent a couple of days just on those rhythm tracks. The first instrument I put down was piano — a very simple, rhythmic piano — and then I did the vocal. I began with a GarageBand loop as a placeholder, then I replaced all that later.

Mettler: Another favorite of mine is “New York I Love You,” with its cool organ lines and smoking-hot guitar fills.

Scott: Yeah, and that one came out of the guitar riff — a bastardization of “Sweet Jane” by Lou Reed and The Velvet Underground [originally on 1970’s Loaded], but slipped into a minor key. I used a couple of hip-hop grooves, one in each speaker, and then I changed the groove at the chorus. I used the electric guitar as the main instrument. In hip-hop style, things were coming in and out of the track a lot, and I also used a lot of “found” sounds — sound effects I had recorded on the streets of New York. [These are identified as “field recordings” in the album credits.]

Mettler: You can hear a lot of those details in the stereo mix, especially when you’re listening through headphones. Basically, each channel for each song has its own character.

Scott: I didn’t think of it that way specifically, but I do think of it all as audio candy. It’s a way to lose yourself in the sound, and also have a lot of fun while you’re listening.

Mettler: You’ve said Blue was always intended as a four-sided album, so that makes me think vinyl is something that’s still important to you.

Scott: Yeah, well, I still think in terms of sides of vinyl — especially when I’m home, and I’m listening to music. Yes, I’ve got CDs, and iTunes with a huge collection of music in it, but my favorite way to listen is to put a side of an album on our little record player, and commit to 20 minutes of listening.

Mettler: Do you have a personal favorite side of a record that you consider to be the perfect 20-minute listening experience? I’d think two favorite artists of yours, Bob Dylan and Prince, each have more than a couple of sides that might qualify here.

Scott: Hmm. What would you say is a perfect Bob Dylan album side?

Mettler: Well, let’s see, I’d say Side 2 of [1965’s] Bringing It All Back Home fits that bill.

Scott: Oh yes! Side 2 has “Mr. Tambourine Man,” “Gates of Eden,” and “It’s Alright Ma (I’m Only Bleeding)” — yeah, yeah, now that is good. And “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue” — my God, that’s good.

Mettler: Didn’t you and Bob Dylan interact in the mid-’80s when you were working on [1985’s] This Is the Sea? What did you guys wind up talking about?

Scott: We hung out a couple of times, yeah. He had “The Whole of the Moon,” which was our hit record at the time, and he invited me down to the studio in North London where he was recording, with Dave Stewart of the Eurythmics producing.

I turned up at the studio with a couple of my bandmembers, because they asked to come with me as well. Bob was very kind to us, and very friendly. He was shy but friendly; an interesting combination. He said to me [affects Dylanesque voice], “Man, I like that song,” over and over. And of course, that made my day.

And we played a bit together too. Oddly, he wasn’t singing; he was just playing lead guitar. The premise of the day was that they were recording instrumentals that Bob would later write the lyrics for. I think some of them eventually came out on those mid-’80s albums of his like Knocked Out Loaded (1986) and Down in the Groove (1987). [Actually, some of the songs worked on during this timeframe ultimately wound up as bonus tracks on subsequent Dylan projects, but not on either of those two abovementioned albums proper.]

It was wonderful to meet Bob. I met him again a year later at a rented house in London. He was in town making that movie Hearts of Fire [released in 1987 and co-starring the single-named pop/rock singer Fiona, best known for her 1985 single, “Talk to Me”]. I remember he had highlights put in his hair for his part. We didn’t play together; we just hung out at that rented house.

Mettler: I think Bob Dylan remains an interesting songwriter in his 70s. Just like you’ve done with this album at this stage in your career, there’s no reason an artist shouldn’t be “allowed” to continue creatively past a certain stage in their lives, as far as I’m concerned. It’s ludicrous to think otherwise.

Scott: It’s absolutely ludicrous to me. But there’s no arguing with the fire of youth. There’s an elemental power that flows through young men and women — and we love that, of course. But to spend the rest of your life mourning its passing or trying to hold onto it seems almost profound to me. There are other “powers” that come through later in life — like experience, and wisdom, and focus. I can focus my energies now in a way I couldn’t even dream of when I was 25. If I had to take the fire of youth over the power of age, I’m afraid I’d have to plump for the latter! [“Plump for” is the British equivalent for “choose.”]

Mettler: And since you mentioned how much Dylan loves “The Whole of the Moon,” which is also one of my own personal favorite tracks of yours, that song seems to have a long life to it. Does that surprise you at all, what that song still embodies all these years later?

Scott: I never thought about it when the song was written — how much longevity it would have. I’m thrilled that it’s still played on the radio a lot in the U.K. and Ireland; I don’t know about here [in the United States]. It’s still a very popular song, and very popular when we play it in concert. I’m very grateful for that. And I love the song. I love singing it.

Mettler: I can tell you “The Whole of the Moon” gets played a lot on the First Wave channel on SiriusXM, and it’s also quite popular on Spotify [currently at 13.6 million listens, as of this posting]. Speaking of that, are you OK with people listening to your music via streaming services?

Scott: Oh, I don’t have any feelings about it one way or the other. It’s a medium, and so I don’t currently have a problem with people using it. But if you’re asking me a question about what I think about the way artists get paid from Spotify, I’ll give you a different answer.

Mettler: Fair enough. I also think Prince, another friend of yours from back in the day, would have appreciated the scope of Out of All This Blue. To me, it’s your version of Sign o the Times. (1987). Do you know that record well? I think it’s my favorite of his.

Scott: I think I do, yes. It’s a very fine record. It’s one of the great double albums.

Mettler: I’m glad you agree. We also have a song title on the Blue album that’s almost a Prince song, but of course it’s not that at all.

Scott: You mean “If I Was Your Boyfriend,” which is reminiscent of his “If I Was Your Girlfriend” [from the aforementioned Sign o the Times]. Yes, of course.

Mettler: Double albums like Sign o the Times, Bob Dylan’s Blonde on Blonde(1966), and Bruce Springsteen’s The River (1980) were viewed as major statements, something that may have gotten blurred somewhat in the CD age.

Scott: Double albums like Blonde on Blonde and [The Rolling Stones’] Exile on Main St. (1972) would all be single CDs. They’re only just over 60 minutes long, short for double albums. But something like The White Album (1968) by The Beatles is a real double album, not one CD. It’s got to be two albums.

Mettler: And it felt that way, too. You’d set aside the time to listen to each side, as they all seemed to have their own identity. Some days you were into Side 4, and some days you were into Side 2. It was sometimes mood-oriented as to how you’d listen to The White Album.

Scott: Yeah. And this album [i.e., Blue] is really a double album. All four sides have very different moods. The fourth side is songs written about and inspired by my wife, the lovely Megumi Igarashi. The first side is five love songs about different women, and the second and third sides are more varied.

Mettler: Is listening to this album in the order you’ve given it to us important to you?

Scott: Ahh, I don’t really care. I recognize that people listen in many different ways now, and they’re not “imprisoned” by the side of an album. They can program it any way they want — and, of course, I’m cool with that. It would be trying to combat reason if I tried to force anyone. But if you choose to listen to it in order, then you should enjoy that experience.