Sound Matters: High Definition Audio For High Defintion Video Page 3

Sonically, the second and third options should be identical, at least for the sound of the movie itself. But a bitstream connection with either Dolby TrueHD or DTS-HD Master Audio can’t carry the secondary audio streams needed for certain special features (like PiP commentary) or the sounds that are often triggered when you make a Blu-ray menu selection. These can pass to your AVR only with the PCM or analog configurations. Therefore, many of us here at Home Theater choose the PCM way.

I personally prefer a bitstream link if all I want to do is watch the movie. My surround processor confirms exactly which format I’m listening to on its front-panel indicator: Dolby TrueHD, DTS-HD Master Audio, or in the case of uncompressed PCM, MultiCh. If I convert to PCM in the player, all I see with any of them is MultiCh. If I want to hear a PiP audio feature, or the menu’s beeps, squeaks, and cowbells, it isn’t that difficult to switch the player to output PCM. This is at least true on a player like the OPPO BDP-83, which permits such a change while the disc is running rather than requiring a full stop and disc reload, as many players do.

Whichever option you choose, if you don’t already have a way to listen to the new high-resolution audio tracks, acquiring the means to do so should be high on your upgrade wish-list. Given a reasonably good sound system, home theater audio has long been superior to what you can hear in the best movie theaters—even with legacy audio formats. Lossless audio has widened that gap substantially.

The Way We Were

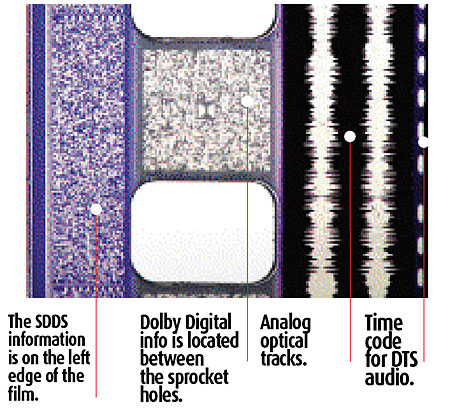

Digital audio began even before CD entered the scene, but its use for movies began in the theater. Cinema Digital Sound (CDS) first launched digital movie sound in the early 1990s, but it was soon driven out by three technically superior formats: Dolby Digital, DTS (Digital Theater Sound), and SDDS (Sony Dynamic Digital Sound). Squeezing the picture, the digital audio, and backup optical analog audio onto a strip of 35mm film presented a real challenge. To solve this, all three of these digital sound formats employ lossy data compression.

Dolby Digital, DTS, and SDDS competed head to head for a few years, but eventually most films were produced with all three versions of digital audio on the same print. This was vital for efficient distribution, as many theaters had installed only one of these systems (or none at all, sticking instead with antique analog optical sound). Fortunately, each format used different areas of the film for their audio data: on the edges of the film for SDDS, between the sprocket holes for Dolby Digital, and between the sprocket holes and the film frames for the optical audio. DTS for theaters is unique in that it records its audio on a separate CD-ROM. It synchronizes this to the picture with a time code on the film next to the optical tracks, where it occupies little space.

It was inevitable that over time some of these formats would invade the home theater market. By the mid 1990s, both Dolby Digital and DTS were showing up on a few Laserdiscs, somewhat changed from the formats used in theaters. Home Dolby Digital sported a higher sampling rate—320 kbps was used in theaters—and DTS had a new coding scheme and a new name: DTS Digital Surround. Then and now, SDDS remains exclusive to the movie house.

With the advent of DVD in 1997, the world of home theater audio turned upside down. The need for audio data compression became more important than ever with the challenge of squeezing both audio and digital video onto a 5-inch disc. Dolby Digital became the standard for multichannel soundtracks on DVD.

Standard Dolby Digital required less data space than basic DTS. On DVD, Dolby Digital runs at a total data rate of either 384 kbps or 448 kbps for all 5.1 channels of sound. On the other hand, DTS ran at up to 1.5 Mbps, both in the home and in the theater. It was this difference that launched an often-heated DTS-versus-Dolby Digital debate that lasted for years. DTS fans argued that their preferred 5.1-channel format sounded far better. (For comparison, CD uses uncompressed PCM operating at approximately 1.4 Mbps for two channels.)

But DTS Digital Surround never really took off on DVD until it developed a half data rate version operating at 768 kbps for films. This let it fit comfortably with the Dolby Digital soundtracks and the extra features that were becoming popular. Even then, DTS was never a dominant player in the DVD wars.

All that has changed with Blu-ray. From the beginning, DTS-HD Master Audio has been running neck and neck with Dolby TrueHD for market leadership, but it now appears to be pulling strongly ahead. Sony, Warner, and Paramount have begun releasing many Blu-ray Discs in DTS-HD Master Audio after years of nearly exclusive support of Dolby TrueHD. They join several other Blu-ray studios that use DTS-HD Master Audio exclusively.

- Log in or register to post comments