Wow, I learned so much by reading this. Already having seen the Jackson film I must simply now watch it again with new knowledge. Perhaps because of time and the scant often poor quality of old Beatles live performances it is overlooked what a fantastic, compelling, and potent band The Beatles were live. I think this new Jackson film sets makes the case that the studio wunderkinds were also one hellacious live band. It is indeed poignant that the rooftop concert was the last time time they performed live. One can imagine that if the breakup did not happen and The Beatles continued they may have resumed proper concerts. Obviously they very much enjoyed playing together for a live audience.

The Making of The Beatles' Let It Be and Peter Jackson's Get Back Post-Production

Post production on Let It Be, actually, started weeks before, not long after filming started, with the creation of an editorial team. "I told Neil, 'We're gonna need a film editor for this. Cause it's not gonna be video," Lindsay-Hogg recalls telling Aspinall. Aspinall's father-in-law was Bud Ornstein, who ran United Artists in Europe (and had, in fact, been a production executive on The Beatles' previous two films). Neil had befriended accomplished film editor Tony Lenny, and introduced him to Michael. "He was very easygoing. I said, 'We're not gonna know what we've got 'til we've got it, and it's probably going to be a long drawn out process, trying different recipes in the kitchen, for what's going to make this picture work. Are you up for changing it a lot?' And he said, 'Yeah, I'm fine with that.'"

Lenny immediately called an assistant editor friend, Graham Gilding, who had just come off working on Carl Foreman,'s McKenna's Gold at Shepperton Studios for 13 months, seven days a week, and was all set for a well-earned vacation. "Tony rang up, probably no more than a week or two after we'd finished and said, 'Do you want two weeks' work?' And I said, 'No, I don't.' He said, "Well if I tell you what and who it's for, you might change your mind.' It took me about 2 nanoseconds to do just that."

The two set up shop at an editing suite in Bayswater, near Covent Garden, with a pair of Movieolas, and, not long after, hired the aforementioned Jimmy Rodden to do the troublesome syncing work. "I think Jimmy aged 10 years on this project," Gilding says.

With their director busy filming The Beatles a half hour away at Twickenham, Lenny and Gilding spent their time assembling the footage by days, based on direction Lindsay-Hogg would come and give them, when time allowed. "I think the process he decided on at the time was that we could cut it in chronological order, day by day, and then put it together in some sort of storyline, of them rehearsing, and what songs," Gilding explains. "And then, intercut with later material, wherever we could," keeping an eye out for clothes changes. "We made up a quick sort of storyboard of what songs they were playing, and what clothes they were wearing," careful to select facial closeups and those of instruments that wouldn't betray calendar changes.

Things really got into gear when the operation was moved to a 5th floor office at Apple, not long after filming was completed. "They had already started on it while we were at Bayswater," Gilding says. "They actually had to strengthen the top floor, to be able to support all of the cutting gear and film," including building a film vault.

Lindsay-Hogg's approach was indeed a chronological one. "I wanted to start at Twickenham, and show them inching their way toward making the songs work," he explains. For the opening, following the Beatles drum head mentioned earlier, "Then it's over to Paul playing the piano, and it's not a rock and roll song. I wanted to say, 'This is going to be a little different Beatles than you were expecting.'"

From then on, he says, the process of piecing the film together was like that of assembling a jigsaw puzzle. "We spent a lot of time looking at the dailies, which just went on and on – mostly because of the syncing issue. But then, when we started to cut, if we had the footage and we had the sound, then we'd start to make something. For example, Paul comes in and talks about writing 'One After 909' – so that's a good place to cut to them playing the song."

The sporadic shooting methodology at Twickenham, and the fact that the group often didn't play through whole takes of songs, led to some sometimes rough cutting, occasionally even with sound not in sync with the image (for example, John's out-of-sync lap steel playing on "For You Blue"). "When we needed a cutaway, because the audio cut or the cameras from a shot wandered off, and we didn't want to keep that move in – then we cheated shots in," Gilding explains. "And sometimes stuff just doesn't sync." Adds Lindsay-Hogg, "Sometimes, you just have to do the best you can. All I can say is, we needed the image, and that's what we had. And. . . tough," he laughs.

One thing was made fairly clear that The Beatles did not want in the film was anything about George leaving. "They didn't come right out and say it, but it was implied that they wanted to keep the image together. It would start with the four of them, and it would end with the four of them, and not much rough water in between. They wanted the story to be that they weren't the four Moptops anymore – but they were still The Beatles."

Occasionally, a Beatle would drop in to have a look – Ringo, in particular, who also had an office on the 5th floor. "Ringo was into film," notes Gilding. "He would wander in from his office to see what we were doing." Gilding, in fact, would go on to edit Starr's 1972 Apple film, Born to Boogie, about/featuring Marc Bolan.

There were a few more visits, though, from Apple's new chief, Allen Klein. "Every so often," notes the director, "he'd say, 'Can I see a little bit?' And he'd see 20 or 30 minutes and then say, 'Yeah, it looks pretty good.'" Though his direction might become a little more involved, at times. "He looked at Part 1, Twickenham, while we were cutting it, and said, 'There's one too many songs in that Part 1. It's 7 minutes too long.' So we found 7 minutes that didn't quite work and took it out. He was pretty smart."

Both the Twickenham and Apple sections were fairly straightforward. Lindsay-Hogg's approach to the Rooftop concert was kept tight, concise and fun. "I didn't want to show the entire concert," which was 43 minutes in length, with some songs given more than one pass, "because I wanted it to be more like a performance. We already had a lot of rehearsal in the runup to the roof, so I didn't want to repeat a song or false start. I wanted it to be like a show."

While one would think managing footage from 11 cameras would be mindboggling, the experienced Gilding knew his way around such challenges. "It was fairly straightforward," he states. "I had it well organized. I had all the pieces numbered, so syncing across cameras was easy. Whenever Tony wanted to cut to an exterior shot, he would just view them and pick the one he wanted."

Interestingly, when Lenny would cut to one of Parrott's street interviews, in the final dub, we hear a reverberated version of the song he has just cut away from, above, behind the interviewee. In reality, though, many or all of those were filmed during breaks, with the music track mixed behind it with reverb, to create the effect.

For both Apple and the rooftop, the team would typically cut to Sutton's Nagra (which had perfect sync to camera), and then, once desired takes had been identified, Lindsay-Hogg would request mono mixes of those recordings, if available, be made by Johns at Olympic, for use in the final track. "If there was good dialogue on the Nagra, we'd use that, and then switch to the 8-track, if we had it," he explains, exercising care, once again with sync, since, with the exception of Rooftop and January 31, the 8-tracks were not synced to camera.

While all of this was going on, the intended accompanying album was taking shape. After a few days' work at Apple, Glyn Johns had a thought. "I felt extremely privileged, watching the four of them, with Billy, doing what they were doing, and almost being a fly on the wall," he says. "They were the biggest band in the world – they had completely rewritten the book on the production of popular music, and had scored a home run every time they did anything. And here we are, the four of them, sitting around, playing together, having a laugh. And I thought this should be the record. It's the perfect way of doing it. Because it would show everybody how they get on with each other, how they interact with each other when they're working."

So beginning on Friday January 24, after working at Apple, he would, on his way home, bring the 8-track reels back to Olympic and mix takes. "I mixed very quickly, over a couple of hours. I strung a few rehearsals together, with a bit of chat and a bit of mickey taking and a bit of jamming, something from the 50s." The process went on for a few days, even drawing "Boy, you sure look tired" comments from the band in the mornings.

The evening after the Rooftop performance, he put his ideas together, and then brought his tape to Apple the following morning and had lacquers cut and gave them to each of them. After giving the disc a listen, "I asked, 'Okay what do you think?' And they, to a man, said, 'You must be joking. Absolutely NO.' So that was put to bed. For me, I just thought, 'Okay, it was just an idea.' I didn't think they'd go for it. But I thought it was pretty cool."

Not long after the end of the Apple sessions, Johns flew to American to work with Steve Miller, eventually coming back later in February and ending up tracking Miller's "My Dark Hour," featuring Paul, at Olympic.

In April, after EMI engineer Jeff Jarratt attempted a mix of "Get Back," for release as a single, the band asked Johns to take a shot at it, which he did, cutting the base track from a take from January 27 with the song's coda from January 28. He also created a mix of "Don't Let Me Down," and the single was rush-released a week later, reaching No. 1 – of course.

At the beginning of the following month, Johns got a call from Paul, asking him to meet him and John at Abbey Road. "I got there, and there was a pile of 8-track tapes in the control room, where we were meeting. And they said, 'Okay, you remember that idea you had? Well, we're now thinking. . . we'd like you to do it. We think it would be a good idea.' I said, 'Okay – great. When do we start?' And they said, 'Well, we're not – we want you to go away and do it on your own. So I took the tapes and went and did it," making his first assembly of the album on May 2, with revisions coming later in the month after notes from the Fabs (including swapping in the single mix of "Get Back" for a previous one).

His approach was a fascinating one, and one which truly reflected what Johns had experienced throughout January with the band. "I witnessed everything that happened, all the rehearsals, and the takes we were honing, as far as being masters. So it was quite simple for me to mentally note what I thought might be good. It really wasn't difficult at all. It didn't take very long."

The album was assembled without "rills" – with no gaps between songs, as one would hear on a typical album. "I wanted it to sound like it was a real event – a real day's messing about, which is pretty much what it is." The second track, a jam from the first day of work at Apple, even begins with a tape "chirp," as Johns becomes aware of something he wanted to capture and told Parsons starts the tape mid-take. "It was as rough and ready as the situation was. That's realism – that's what happened. 'Quick – get in there!'" For the best incidental bits, such as now-iconic quips from Lennon, "I probably just went through the stuff that I remember being good and picked bits." The album was completed on May 28.

During one of the listening sessions at Olympic, he says, "They were all in the control room, and I said, 'Now, listen – I was retained to engineer your record – which is fine. However, as it transpired, I've actually produced it. I don't want a royalty, but I wouldn't mind a credit.' And they all looked at each other, and John said, 'Why don't you want any money?' He was suspicious of me, because I didn't want any money. I said, 'I don't think I deserve it. I wasn't retained for that reason. But I did produce it, and it would obviously be really good for my career if I got credit.' As it turns out my record never got released, and that issue never came up again."

Acetates of the Get Back album were previewed to several American radio stations – and soon after resulted in bootleg copies being put into circulation. Johns went into a record store in San Francisco in 1970, "and there was my bloody album being sold!" he recalls. "I asked to see the manager, and told him if I were the producer, he'd be screwing me. But he didn't give a monkey."

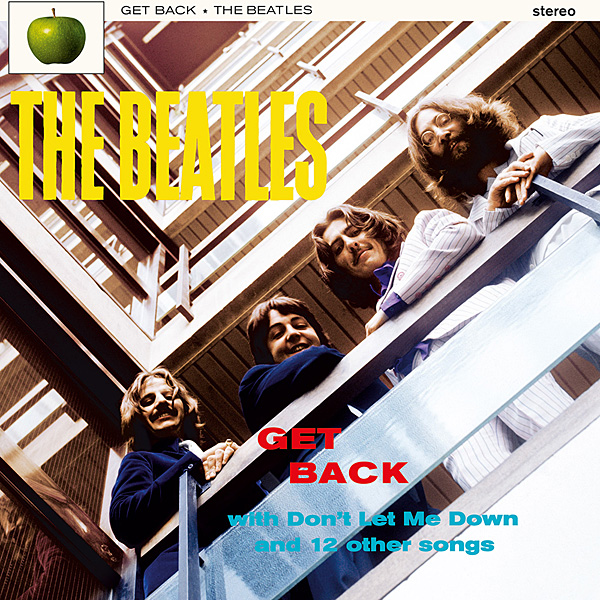

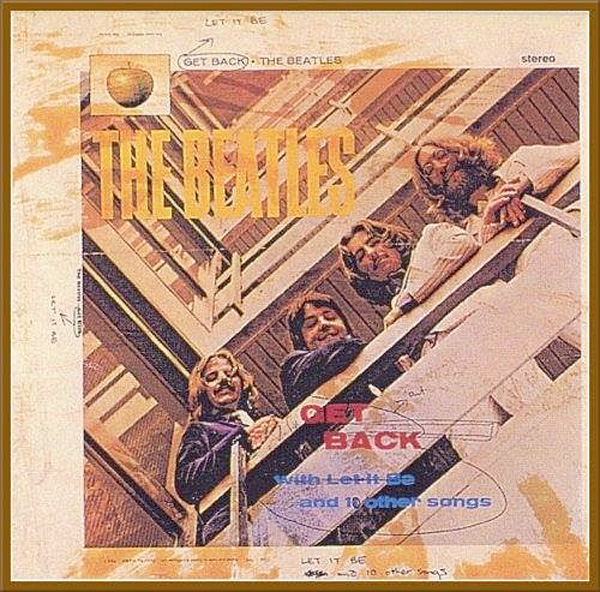

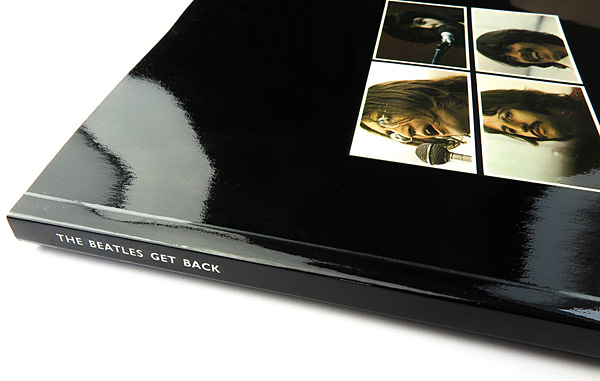

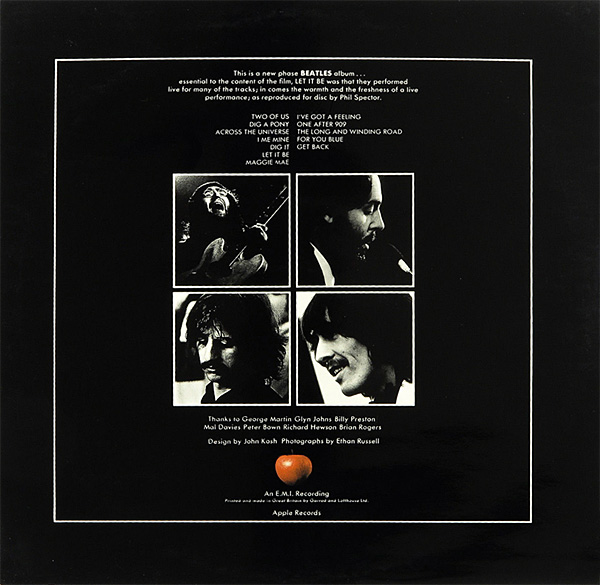

A sleeve for Get Back was actually prepared, by Apple's in-house sleeve designer, John Kosh. Kosh had first come to Apple after meeting John & Yoko, while he was designing The Royal Ballet/Opera's Art & Artists magazine in 1968. They asked him to create their Christmas card that year, and, by the beginning of 1969, he was designing album and single picture sleeves for Apple artists such as Mary Hopkin and James Taylor, and, into the Spring, for George's and John's solo albums. "I was kind of useless at psychedelia," Kosh says. "I was doing minimal stuff, which was what appealed to John & Yoko. Lots of black, white, negative space." Kosh's "house style," with color images framed in white or black space, seen on his picture sleeves, eventually formed the basis of the final Let It Be sleeve design.

For this cover, The Beatles – likely Lennon's idea, Kosh thinks – decided to have themselves photographed at EMI's Manchester Square office, in an exact replica of that used on their first LP cover, Please Please Me – not only taken by the same photographer, Angus McBean, but replicating their exact poses, too. "I was suddenly presented with these photos, and told, 'This is what Get Back is all about. We're getting back," he recalls.

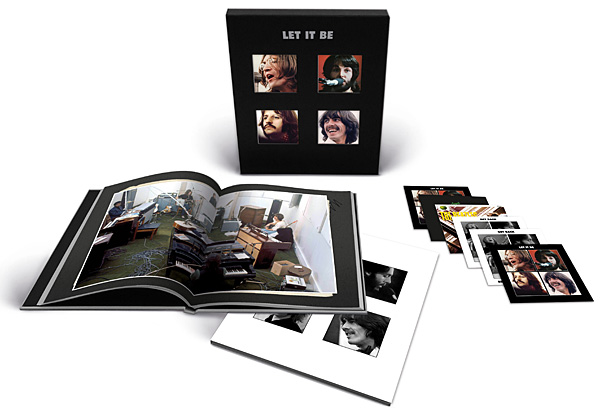

Glyn Johns's Get Back LP finally did see release – with Kosh's cover – in October 2021, as part of the Super Deluxe Edition of Let It Be, mastered ("Not 'remastered' – it's never been mastered before," he points out) under Johns's direct supervision at Abbey Road.

Film editorial continued through this period, until a 2-hour cut was completed, which was then shown to the band on July 20, 1969 – the night Neil Armstrong stepped onto the surface of the moon – at a screening room on Oxford Street in Soho. Attended by all four bandmembers and their spouses – George also brought his father, Harold – the group saw the 16mm projection, and, Lindsay-Hogg notes, "Everyone seemed quite happy with it, amazed that something had come out of it. And we had the Rooftop, which they were thrilled with." A celebratory dinner was held at a nearby restaurant, including Paul and Linda, John and Yoko, the director and his girlfriend, Jean, and Apple's Peter Brown.

A few days later, though, Lindsay-Hogg received a call from Brown, listing suggested cuts that were desired. Besides at least one song (unknown which) and some conversation, Brown had one specific note: "Too much John & Yoko." "I said, 'Well, I don't think so," and he said, 'Yeah, but I have had three phone calls this morning about that.' The thinking was that The Beatles were cohesive still, that John was still part of the group. And the pieces we cut out, there was more exchange and intimacy between John & Yoko, which could look like they were in a separate world – which they were."

Within the remainder of the 40 minutes that were cut was music, as well. "The only way to remove those was to take whole songs out," Gilding explains. "That's the only way you can cut the time down, quickly, without really mucking around with it too much and making a mess of it. If you start off one song, and they're developing it, and they're cross chatting, that's the interesting part. But if you then go to another song, and another song and another song, it's very difficult to cut that down succinctly, to tell the story. It's easier to just take the whole section out. And you'll never miss it."

Those cuts took place over the rest of the summer, with Gilding also beginning work on a new Apple project, supervised by Aspinall, The Long and Winding Road, Apple's initial pass at telling The Beatles' story, as would later be done in 1995 with The Beatles Anthology.

Another change also occurred during that period, which was the shift from the film being shown on television to being released as a theatrical feature, something Lindsay-Hogg says was instigated by Allen Klein. "Once he got involved, he was thinking theatrical, not television, and for a variety of reasons," including wanting to interest MGM in the release, on which Klein was hoping to get a seat on the company's board, he says, "luring them with the Beatles movie, which he would maneuver away from United Artists – who weren't sure they wanted it anyway. The Beatles had a three-picture deal, but UA didn't necessarily want a documentary. But then, later, The Beatles were breaking up, and it was that or nothing for UA. And that's partly why the release was held up, into the following year."

The change meant a change to the film's aspect ratio, going from the 16mm 4:3, essentially square, frame to 1.85:1, common for theatrical films. And changing the shape of the frame, which meant not only cutting it top and bottom, but also other changes, required "pan and scan" adjustments. "That was a bloody nightmare," Gilding notes. "It wasn't just top and bottom, but, also, we had to move things slightly and blow them up. And with 16mm, there's already a lot of issues with the grain of the image getting increased, but also dirt and hairs in the gate. So we went through, shot for shot, at Apple, marked it up and sent that in to Technicolor," who then performed the pan and scan and created the fine grain internegative.

The film was mixed at Twickenham's scoring stage by one of the company's seasoned re-recording mixers, Gerry Humphries. Humphries, soon after, became the studio's Managing Director.

Another screening was held in mid-September, a week or so before the release of Abbey Road, of what was essentially the final cut. Afterwards, Lindsay-Hogg recalls, the group (same as before) went out to a London club, The White Elephant on the River. "The White Elephant had a discotheque downstairs, and we all went down, where there was music. And as Paul was leaving, I said to him, 'This has been quite a ride we've been on, ever since we talked about it in December.' And he said, 'Yeah, but I think we've come up with something good.'"

After the final edit was completed, it was realized that some changes to the Get Back album would be required – not the least of which was a change in its title to Let It Be, to reflect what was now going to be the focus track – and the film's title.

On January 3 and 4, 1970, George Martin went into EMI with Paul, George and Ringo – John was traveling – and added overdubs to "Let It Be," including brass, background vocals and a new lead guitar part from George. (The one recorded this day was a rocking, distorted part, whereas one he had added in April 30, the previous year, was, like the one he had tracked live, played simply through a Leslie.) The three also recorded George's "I Me Mine," which appeared in the film at Twickenham, but had never been recorded at Apple on 8-track. These sessions marked the last true Beatles recording session.

Within a few days, Johns mixed "Let It Be" (curiously, keeping the April 30 Leslie'd lead, not the new one) and "I Me Mine." He was also asked to remix "Across the Universe," which appeared in the film at Twickenham, but was never re-recorded at Apple. The song had been recorded in February 1968, during the "Lady Madonna" sessions, but had remained unreleased, until December 1969, when it appeared on a charity LP. But it was given a fresh mix here by Johns. (His mixes of that track and "I Me Mine" appear on an exclusive EP, featured in the Let It Be Super Deluxe Edition.)

Johns was then asked to update his Get Back LP from the previous May, dropping "Teddy Boy" (which was now not appearing in the film), and adding in those two tracks, as well as a few other changes. Kosh also updated his sleeve text, to reflect the new title.

It was all for naught, though. Johns's mix of "Let It Be" (backed with an odd Beatles leftover, "You Know My Name (Look Up the Number)") was released on March 6 as a single, but his album was finally discarded and Phil Spector was brought in later that month to begin a new pass at remixing the album.

Spector worked in EMI's Room 4, which was a mixing studio, with veteran EMI engineer Peter Bown (pronounced/rhymes with "town"), who was assisted by tape op Roger Ferris, who had only started at the studio a few months prior.

Spector wasted no time rubbing Bown the wrong way, mostly due to his insistence on keeping his rather large bodyguard, George, in the tiny work room. "I remember Peter saying, 'Look, this isn't the States,'" says Ferris. "This is a place where you can rest and be easy.' But Phil wouldn't have that. And George ended up sitting outside, on a chair, for hours on end."

Work began on Monday March 23, and continued through the week, with Spector and Bown mixing and editing his own selection of takes, including several more from the Rooftop not utilized by Johns. Edits involved lengthening both "I Me Mine" and "Let It Be," by copying parts of each to extend their lengths, and some mixing work in prep for Spector's orchestral overdubs to three tracks, "Across the Universe," "I Me Mine" and, most famously, "The Long and Winding Road." A day was also spent creating selections of Lennon snippets, some of which Johns had used.

By week's end, Bown had had enough of Spector's peculiarities and walked out, Ferris notes. "On the Friday, Peter just didn't turn up. So they phoned Mike Sheady, and he came in and worked those two days," Friday and the following Monday," Bown eventually coaxed back by studio manager Ken Townsend, who, Ferris notes, personally went to Bown's house and asked for his return.

For the orchestral overdubs, recorded in EMI's large Studio 1, Spector utilized arranger Richard Hewson for two of the tracks ("Universe" was done by Brian Rogers), who had come into the Beatle world via his friendship with Peter Asher, when a score was needed for Mary Hopkin's first single, "Those Were the Days," released the same day as "Hey Jude" in August 1968.

"I got the call about 7:00 p.m. It was to be recorded the following day. I hate working at night; I'm not very good at it," he recalls. Hewson went to Apple and picked up the rough mixes of "The Long and Winding Road" and "I Me Mine." He quickly got to work, receiving plenty of phone calls from Spector through the evening. "He said, 'I want it orchestrated with a massive orchestra.' All through the night, he kept ringing up saying, 'Let's have some more violins. Let's have three harps instead of one,' and all that. There were so many musicians in the end that we couldn't get them all in! We actually, literally, had to shut the door and say there's enough."

At the session the following evening, he says, "They turned the lights out in the control room. He was in there sitting in the dark with all these weird guys. I was actually a little frightened to go in there."

Spector had the orchestra play the parts repeatedly, which quickly wore on the musicians. "He kept going, 'Let's have another take.' He didn't ever want to listen to a playback, he just wanted to play it over and over again. The guys were saying, 'We played it. We can't play it any better.' It wasn't that difficult music for those guys. They're brilliant musicians. The first reading through is pretty well perfect, and the second one is right on. Eventually, after the tenth time, they got fed up and left."

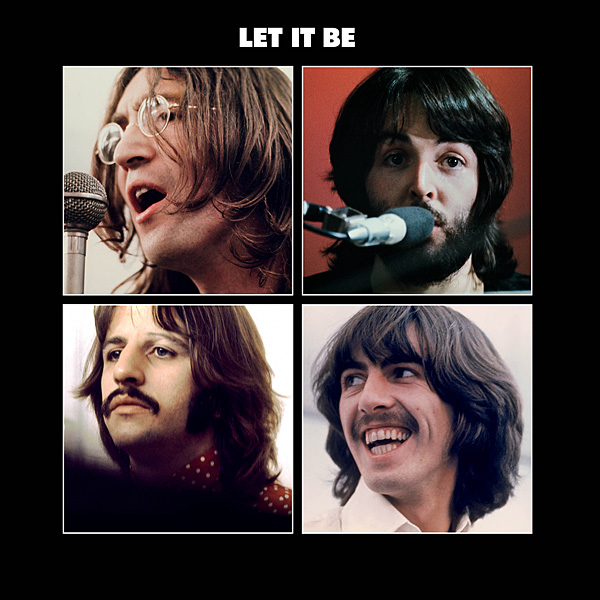

With the "Get Back" theme now superseded by "Let It Be," Kosh was asked to create a new sleeve design, which he began in late February 1970. He chose that of his "house style," with four separate Ethan Russell photos, each in its own square, surrounded by black. "They had had the White Album, so this was the Black Album," he states. The design first appeared on the "Let it Be" single's picture sleeve in early March.

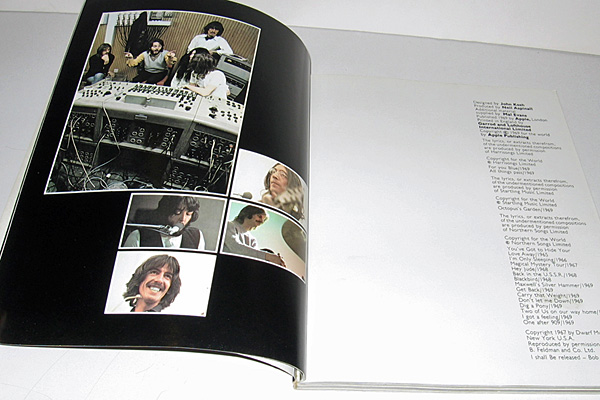

Accompanying the LP was a fantastic 160-page book, featuring a wonderful selection of Russell's photos, accompanied by transcripts of conversation taken from throughout the Nagra recordings. The text was transcribed by Derek Taylor's assistant, Mavis Smith and a colleague, and edited by Rolling Stone's Jonathan Cott.

He and Russell actually began work on the book the previous year, with a meeting at Apple on Saturday February 2, just two days after the Rooftop concert, Russell remembers. "We worked very hard on that together, the two of us doing the photo selections, and Kosh doing the layouts and mechanicals, all the way until we went to print." Notes Kosh, "We had this huge light box, and just went through his transparencies of worked it out, and I'd lay it out as we went along."

The book, completed before the album title change (it still had "Get Back" on its spine), was printed by sleeve printer Garrod & Lofthouse. It is famously known for falling apart, due to the choice of cement used on its binding. "George used to call them 'Garage & Shithouse,'" Kosh laughs.

There was one detail which Kosh added to the back of the package, whose reason today remains still unexplained – a red Apple logo. In the States, United Artists, who had the rights to release Apple's album, as part of their film deal, unfortunately chose not to issue the deluxe box set package of Kosh's issued in every other territory, instead opting for a straightforward gatefold, with a small selection of a few of Russell's pics. But, as ordered by Apple's U.S. label manager at the time, Al Steckler, it was given red Apple Records label backdrops, instead of the customary green.

In October 2021, the album was reissued as a Super Deluxe Edition by Apple/Ume, featuring a brand new remix by Giles Martin and his engineer, Sam Okell, both of whom have crafted the band's previous 50th anniversary deluxe sets.

As he discovered while studying the album sessions in detail, Okell notes, "There's so many days of material, you can imagine Spector going in cold, and having to decide what to do," unlike Johns who was there for every moment and knew the material intimately. Says Martin, "Spector's remix was very different from Glyn's. Glyn's take was to be as raw as possible. That's the mood they were in when they made this – more of a live vibe. Where Spector is always trying to add. . . Spectorness to a project."

The remix was far simpler for the duo than, say, Sergeant Pepper, which had multiple reels of overdubs. "There was very little bouncing down, except for the Spector work," Okell notes. "It was mostly pretty straightforward 8-track recording." Of Johns's stereo Ringo drum recording, after working for years with EMI mono drum tracks, "We're just so used to one great-sounding, single drum track. So to have him in stereo was a luxury."

Martin likes to help out some items recorded on a single mono track, particularly the strings tracked by Spector. "We re-amped the orchestra, to give them a bit more, playing them back into the room in Studio 2 at Abbey Road, and miking the room," and doing so in two passes to create stereo. "You have to be careful how much space you have around them. You can create a pretty good stereo out of mono, just by facing a speaker next to the control room glass and recording the room."

"Across the Universe" presented an interesting challenge, since it was originally recorded on 4-track, and then bounced, at a different speed, to 8-track by Spector/Bown, and then the orchestra added. Abbey Road engineer Matthew Cocker, extremely adept at syncing multiple reels in Pro Tools – which he does by hand – first copies the original 4-track, using the 2009 remastered version as a guide, to match its speed and pitch. Then the orchestral recording is synced to that material, prior to remixing. "We start with the end version, and work backwards from there," Martin explains.

Martin's approach to the Rooftop mixes – as prepped both for the album and Jackson's soundtrack – he says, "I always think about perspective in mixing. The rooftop is fairly dry, and I try to think about, 'What's it like being in front of the band?" – to essentially be in the position camera operator Colin Corby found himself in. "And there's also a power in the rooftop, which is not on the rest of the record, because it's a performance. And it's very much old style Beatles, in a way, how they were on the floor of Studio 2."

The dialogue bits, such as the Lennon quips, were originally sourced from both 8-track reels and the 1/4" Nagra reels, which would have been spliced into the original 8-track reels at the time of mixing in 1970. Here, Cocker once again, added them into the Pro Tools files, synced to their exact location, as we know them.

When Spector created his Rooftop mix of "Get Back," he actually used a studio take, and cut in rooftop chatter from before and after, to give the appearance that the performance itself was from the Rooftop, even though it was not. "And you do buy it, as we have for years," Okell states. While the original mix would have been made by, perhaps, cutting in the chatter directly, Okell crossfaded them, in and out, to give a truly natural feel.

The process for selecting the previously-unreleased bonus tracks was the same as it's been for the previous reissue projects. Historians Mike Heatley and Kevin Howlett (the latter wrote the liner notes for the box set) sit with Cocker at Abbey Road and, literally, listen to every single take. They then produce a recommendation list, from which Martin then selects what he feels are what fans should really hear. "Kevin might say, 'We have to put this song on, fans will love it,'" Martin notes, "but I might say, 'But I don't think it sounds very good.' You really have to limit yourself, and also avoid repeating. How many versions of 'Get Back' do you really want to hear? It's about getting the right balance. Because you're telling a story, showing how a song developed."

The outtakes include bits that fans have read about for decades, which help dispel myths – such as a 1969 version of "Please Please Me," which, it turns out, is just Paul noodling a bit on the piano, before beginning a take of "Let It Be." And while fans, of course, want all 160 hours of Nagra recordings, he notes, "The funny thing is, most of the people making those complaints have all that stuff anyway. They say, 'But I want YOUR version!' You want my version of a mono Nagra of this?'" There are plenty of gems for fans to enjoy, nonetheless.

- Log in or register to post comments

The Beatles' iconic album "Let It Be" and Peter Jackson's documentary "Get Back" offer a captivating journey into the band's creative process. Jackson's film provides an intimate look at the making of the album, revealing the camaraderie and challenges faced by the legendary group. It's a must-watch for any Beatles enthusiast.

https://theauthorconnect.com/how-to-write-a-childrens-book-tips-and-tric...