Wow, I learned so much by reading this. Already having seen the Jackson film I must simply now watch it again with new knowledge. Perhaps because of time and the scant often poor quality of old Beatles live performances it is overlooked what a fantastic, compelling, and potent band The Beatles were live. I think this new Jackson film sets makes the case that the studio wunderkinds were also one hellacious live band. It is indeed poignant that the rooftop concert was the last time time they performed live. One can imagine that if the breakup did not happen and The Beatles continued they may have resumed proper concerts. Obviously they very much enjoyed playing together for a live audience.

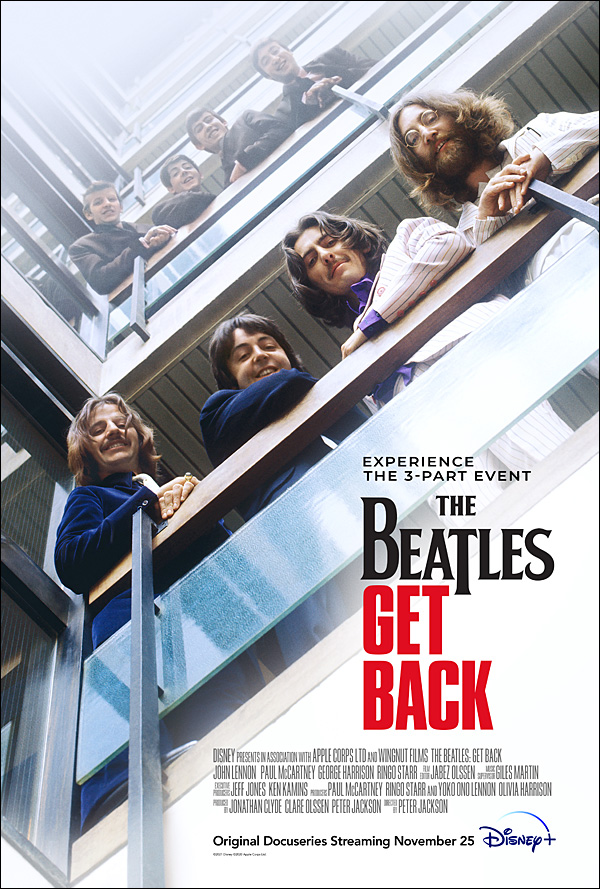

The Making of The Beatles' Let It Be and Peter Jackson's Get Back Peter Jackson's The Beatles: Get Back

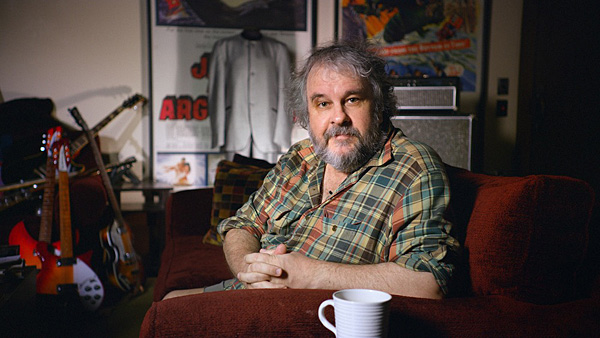

In 2018, Oscar-winning director Peter Jackson was in London for meetings with his team, about their previous, incredible World War I documentary, They Shall Not Grow Old. At the time, Apple had been considering creating a possible interactive exhibition, using augmented reality – something they knew Jackson had some experience with. Aware of his presence in town, Apple execs Jeff Jones and Jonathan Clyde asked if he might be able to come for a visit. While talking, possible content was discussed, and the idea of using Let It Be rushes – the unused footage from the original reels shot for the film – came up, recalls producer Clare Olssen. "Then they mentioned that, 'Oh, we're thinking of doing a documentary with this.' I think, then, Peter put his hand up and said, 'Hey – if you're looking for a film director who might be willing to take that on, you might have found one!'"

He asked to see some additional footage, and time was arranged for him to view in Apple's board room for several days, bringing in his green tea and watching for hours. He did so with some trepidation, fearful of possibly watching hours of miserable interactions, as has been supposed for decades. "But his mind was blown with what he saw. There was so much of their friendship, laughter and camaraderie. And he thought, 'This is a story that needs to be told.'"

The process needed to be continued, so Jackson asked Apple to send over the materials to Park Road Post, in Wellington, New Zealand, the post production arm of his company, Wingnut Films, so that he could view all of the materials. These included a total of 57 hours of scans of film (as 2K DPX data, from an ARRI scanner), both the rushes mentioned, as well as a scan of the original cut negative of Let It Be itself.

In addition, fortuitously, Apple sent, via large palettes, Lindsay-Hogg's and Lenny's original work print – the black and white cut an editor would use to try out and assemble their edit, during the editing process, which also came with its "sep mag" – the audio the editor matches to picture while editing, made of transfers of audio from the Nagra recordings. "There were something like 500 reels of Nagra recorded," states Jackson's editor, Jabez Olssen (who is also Clare's husband), "and 40 of those are still missing. But the sep mag had 2 ½ hours of audio which has never otherwise been recovered, which we transferred and digitized. It's material that bootleggers and fans who've studied the Nagra recordings have never ever heard."

The original Nagra recordings, totaling about 160 hours of audio, were stolen by an Apple employee not long after the film was completed, and have been bootlegged for years. Interpol finally tracked them down in 2003, and they were recovered and returned to Apple.

The work print also contained bits of picture that the team also otherwise didn't have, Clare states. "It was black and white, of course. But even to find those little gems, that have been missing, which were forever gone, was really exciting."

Once a complete audit of audio was made, they became aware that there was some audio still missing. "So we did a deep dive, to see what's out there, in terms of bootlegs," she explains. "We had people researching in the UK, to dig up as much as we could. And Peter himself has a large collection of bootlegs. It was a real forensic deep dive," and by November 29, 2019, the team decided they had everything they were going to get.

The most difficult task – as had been the case during the production of the original film – was syncing audio to picture, again, due to the absence of clapperboards during production. In the 1990s, long before the days of digital workflows and editing tools, Apple, Jabez explains, had begun the process "by buying up all the bootleg albums they could get, and using that audio to try and sync to picture, on videotape – all done by eye and ear." Once the Nagras were recovered, they repeated the process, using the true digitized versions of the Nagra tapes. That process was done for Apple by engineer Dave Wooley, and continued at Wingnut by their own Dan Best, who, along with Jabez, visited Wooley, who walked them through the process he had developed to accomplish the task.

Helpful, Jabez notes, was the presence of the sync pulses generated by the cameras and recorded onto Track 2 of the Nagra machines. "But because the A Camera was connected to Peter Sutton's A machine, and B Camera to his B machine – and, typically, only one was recording at a time – the pulses are often missing. But we would view the pulses' waves, and see, for example, a 20 second bit of camera activity, and then go and look for a camera shot from that camera on that day with exactly that length." The tedious process took the better part of a year to complete.

One interesting thing, by the way, that came from now having picture to coincide with the well-known Nagra audio, was context. "The minute you put picture with it, you see the context with which something was said," says Clare Olssen. "Is something which, read as a transcript or heard on its own, said in anger? Or are they saying it with a smile on their face, giving someone a little nudge in the arm after they say it? You see their friendship, the eye contact and the sparkle in their eyes."

The first step, before handing the footage over to Jackson and Olssen, was an initial base restoration, performed by Park Road Post. Since the rushes and Let It Be negative scans were done at different times, their color did not match, so the two were given an initial color grade, says Senior Colorist and Creative Supervisor Jon Newell.

The initial restoration pass was done via a semi-automated process, to allow a quick turnaround, "So that Peter had something to work with and could get a sense of how much detail existed and had good images to cut with," Newell says. This also included frame stabilization. "There are lots of hairs in the gate," adds Technical Director Ian Bidgood, "but also, even though they had tripods, the image was very, very shaky. And 16mm cameras always had a bit of float So we had to stabilize it all," creating a floating frame within each frame's edge, in which to place the stabilized image.

Once receiving the footage, Olssen reinserted the Let It Be camera negative into the lab reels, in order to have what would have been the complete reels, as they would have been received back from the lab for dailies in 1969. So before sending the materials to editorial, Park Road also had to recreate missing frames. "You can't fine-cut 16mm," says Newell. "So during the original cut, you lose a frame or two. So we digitally recreated those frames, so that, when the Let It Be camera negative material is reinserted, it's seamless, rather than have a hop where two frames are missing," using software that can interpolate that small amount of movement (they would also use their own small visual effects department to achieve ones which were more troublesome).

Once he had rebuilt the original lab reels, Olssen took the material for each of the 21 days (The Beatles worked for 22 days, but were not filmed/recorded on Monday January 20) and assembled master sequences for each day, typically between 10 and 12 hours long. "We had all of the picture, and where there was audio with no picture, just black" on his Avid timeline. "And if the two cameras were running at the same time, we would split screen them."

He and Jackson then began watching through all of those master sequences, and, where the cameras weren't running but Sutton was recording, "we would keep listening to the audio." After watching through the sequences, the two then watched again, this time, making selects – picking those pieces that looked interesting. "And we found that we had to keep coming back and watching them, because, as they story evolved, we realized things that didn't seem important, we suddenly realized were important, that they were good setups for something that happened a few days later. So it was a continual layering and iteration, fine-tuning and reexamining what we had."

Fairly soon, it became clear the way to tell the story was day-by-day. "We discussed if there was any other way to tell the story, which could be less linear – like following a song's path from initial introduction through to recording," he explains. "But so much of the narrative is emphasized by looking at things in a chronological order. There's so much about what the band's trying to decide what they're doing. And that story is best told in a linear fashion."

A structure soon became apparent, too – Act 1, George leaves the band, Act 2, the band working out what the future is, and Act 3, their climactic triumph of their Rooftop concert.

The two put together everything they spotted that they found interesting, and, after about a year's time, had an assembly that was about 18 hours in length, which they then could begin whittling down. "The story forces itself upon you, because you see the same things coming up again – those items, as well as the story of every song, particularly ones created during this time, and seeing them as they develop. And then, as we would cut it together, it was those things that had a narrative structure to them, that took our attention – those would be the things to stay."

When cutting the Rooftop, with so many cameras' worth of content available, Olssen set up his screen with each, as a multi-image. "It was like vision switching with live television," he explains. "But the idea is that this is the best Beatles concert experience we now have. The cameras are up close and personal. We've watched it hundreds of times, and it never loses its impact."

If they are nothing else, Jackson and Olssen are master storytellers, as evidenced by their years of work together. So a big challenge, while showing the band's day to day process, was how to keep the narrative flowing and not have viewers lose interest. "There was always a question of how much music do you have? How many times do people want to see the same songs being rehearsed?" he notes. "There would be little interesting things, in certain rehearsals, that we wanted. But then it's a matter of how much of the song do we need, in order to have this interesting bit? Do we need to see the song start, do we need to have each song finish? As we went, we got braver at just cutting in or out of a song, so you just see the good content."

Among the most fascinating qualities of their cut is viewing the process of The Beatles – often Paul – writing a song, seeing it from its very start, as he noodles on the piano or his bass, finding a melody, and, as time passes, working the song out with his bandmates, seen, for the first time, as the group process it truly was, likely throughout their career together. "That's really the thrill of this project, the thing Beatles fans will take away from this. We tend to take for granted that these works of art arrived fully formed. And everyone tends to think that, by this time, they all worked individually. And you can see, they all work on everything together."

There was, of course, the decision of how much, if any, of what appeared in Lindsay-Hogg's film to include in the new project. "We did start off wondering whether we should attempt to not include any footage that had been in Michael's film, so we could say 'This is entirely new,'" Olssen explains. "But we realized there are very iconic moments that would leave an incomplete picture if we didn't include," which they accomplished by making use of alternate shots, if they were available, building out the scene (such as the Paul/George "If you want me to play, I'll play" moment) – or simply using the shots as they had appeared in the original, as fans know and love them.

Both Jackson and Olssen are huge Beatles fans, so an eye was always kept open for tidbits that diehard Beatles fans would simply love. For example, on Day 1, John and Paul spot a Hare Krishna member friend of George's, sitting across the stage, and John asks, "Who's that little old man?" with Paul answering, "Very clean" – a running gag straight out of their first film, A Hard Day's Night. Says Clare, "They've been able to pick up subtleties in this footage that are really meaningful, because they know so much about the history. Those wee moments are actually fundamental to this history. The project was in really good hands." Olssen also assembled a 10 minute prologue, which starts Part 1, summarizing The Beatles' history – and including the original references, such as the above, for viewers who are not quite as familiar, so that they will make the connection later.

Once Jackson and Olssen had developed their cut, true picture restoration could then be performed on not only the footage being used, but also the "action" part of the frames – the areas of each which would appear in the final image.

Their main brief from Jackson, Newell says, was "Peter just wanted to make it look like it was shot yesterday. That it's contemporary. It doesn't have to be weighed down with the fact that it's film from 1969, which is grainy and has issues. It was to take out anything that dates it, and just make it look fabulous."

Once the selected images were established, a team of three restoration artists got to work, going frame by frame – literally pixel by pixel, in some instances, finding every single flaw, Newell says. "It's very labor-intensive, but we have excellent cloning tools, a variety of software systems."

There was lots typically associated with 16mm film, including dirt, grain and plenty of hairs in the gate, particularly on the Rooftop. "They were shooting continuously, so they didn't really have that discipline of being able to do the standard gate checks that you normally do on set. They didn't want to miss anything, and were quickly reloading. Some shots had four to six hairs in the gate, which all had to be removed."

Sharpness was also an issue, again, much to do with 16mm and the shooting methodology. "Not every shot was perfectly in focus. It was shot documentary style, so it's quite challenging, especially when on the long end of their zoom lenses," quite noticeable in the Paul/George discussion from Day 3. "We struggled with that one a bit. Because the lens is a lot softer, and I don't think very high quality. And because Tony was far away, there's not a lot of light coming through the lens."

The quality of their restoration had additional significance in editorial. Just as Tony Lenny had done, Olssen needed to intercut shots – "cheats" – from other moments, due to the limitations of a simple two-camera shoot. "For Peter to make it work," says Bidgood, "we had to intercut with other shots. So being 16mm, and quite grainy, that's where we had to put a lot of work into, to try and make the other shots look like they're from the same as the main shots, particularly for closeups he used," using imagery that's zoomed in from another frame. The effect is absolutely seamless.

While the frames they were working in were the original 4:3, the final image is, as was its theatrical predecessor, 1.85:1. While there might be purists who insist that the complete, original framing is what should be presented, Newell notes, "It's not been made for archivists. Nothing has been lost here – it's just a different interpretation." Adds Clare Olssen, "We want to give people that sense of being a fly on the wall – and so we want them to be able to relate. And that's a filter that gets taken off which makes it relatable to an audience viewing it today." As before, the director and editor made the choices of which part of each frame to make use of to do just that, a process that Jackson continued to adjust even into the final color grading.

The biggest challenge on the audio side was the Nagra tapes: single mono recordings, containing both music and dialogue, and often at the same time, as musicians tend to noodle on the instruments while talking with a bandmate. "I remember thinking about a workflow for this," recalls Sound Supervisor Martin Kwok, "and thinking, 'What are we supposed to do here? It's all on a single strip of tape. For a good week, I was just, 'There's no clear path through this, is there?'"

The main issue was indeed how to separate voice from the other sounds on the tapes, so that Jackson could identify what was being said, to understand the narrative. "I remember in an early conversation with Giles Martin, Sam Okell and Apple's Jonathan Clyde, Jonathan leaning in to us, saying, 'Have you found the silver bullet yet?'"

Source separation was the key. During COVID lockdown, he and the audio team, including re-recording mixers Michael Hedges, Brent Burge and others, spent time working on some of Jackson's back catalog, using a piece of software, Deezer Research's Spleeter, which uses a neural network to split audio stems apart. "It wasn't perfect, but we could see results." A few months later, they took a trip to visit a friend of Kwok's, who was a forensic audio specialist with the New Zealand police, who were using CEDAR Audio's Cambridge for investigations, such as being able to hear a suspect's phone conversation in a noisy room.

They eventually came to use a combination of softwares, along with turning to A.I. – machine learning. "You give it models, say, samples of George's guitar, or John's, as well as their voices," and the system begins to learn which is which, eventually able to separate those out, to some degree, from their speaking voices, based on samples of "a good clean voice," which the system learns. And, of course, being huge Beatles fans, the system was named Machine Audio Learning – or MAL. "He's one of our heroes," says Kwok, of The Beatles' version. "So we live with Mal every day."

The result, in mixing, particular for the Atmos mix, "is to make sure that the dialogue comes forward." And creating spatiality, from a mono recording, for music, Burge explains, "You won't hear instruments left and right. But you'll get a sense of the movement, sonically, across the soundstage. So we can place the singing into the center, while having the rest of the instruments a little wider and into the room." Adds Kwok, "People who've had the bootlegs of the Nagra reels all this time will be enlightened in new ways. It's very hard to listen to those mono recordings and make sense of what's going on. This offers breakthroughs which shed new light on this history, which was really Peter's goal."

The jump from Twickenham to Apple, where there was an additional audio source – Glyn Johns's 8-track recordings – makes for an entirely different experience. "We use both the Nagra and the 8-track, but the 8-track wherever we can, which is what Peter wanted," says Burge. "It's interesting, regarding the Atmos mix – we start at Twickenham, which is a narrower, and then Saville Row is where we enter 8-track. So suddenly, we can start to widen it out. It's a large sounding room mix."

For the Rooftop, Martin and Okell had provided the mixers stems with which to do their work. "Here," Burge notes, "we have all those things that we don't have in a confined studio, where we can open up the soundtrack into the room. We can really knock people off their feet. We've really focused on making it a live performance – it's not an audio playback of the recording from the rooftop. Peter wanted it to feel like we are up on the stage with them, not just sitting in the middle of a stereo mix."

As with the previous film, the film cuts occasionally down to the "man on the street" interviews, "And then we go crash back off the stage – BOOM – back onto this big sounding band width. It's amazing."

Amazing is the word. "What I saw in them that day was the three kids, plus Ringo, from Hamburg," says Michael Lindsay-Hogg. "I saw the rock and roll band reconstituting itself. I saw them being really happy, to be playing with each other, having this silly adventure up on the roof, not knowing what was going to happen.

"But if you look at the exchange of glances, between Paul and John and George and Ringo, they were having the absolute best time. And they were showing that they were really the best rock and roll band of all time." Adds Ken Mansfield, "They came up on that stage that day without a soundcheck, but they went back down the stairs with a soul check."

- Log in or register to post comments

Hey, thanks so much! It was quite a lot of fun to research and learn about from these great folks. I'm glad you enjoyed it.

The Beatles' iconic album "Let It Be" and Peter Jackson's documentary "Get Back" offer a captivating journey into the band's creative process. Jackson's film provides an intimate look at the making of the album, revealing the camaraderie and challenges faced by the legendary group. It's a must-watch for any Beatles enthusiast.

https://theauthorconnect.com/how-to-write-a-childrens-book-tips-and-tric...

.....Just a quick correction to info mentioned in the article about a camera used to film the "documentary"....

The article states: "The (Arriflex 16BL) cameras had 400 ft. film magazines, which ran for 21 minutes."

Actually, 400 feet of 16mm only lasts for 11 minutes if shot at 24 frames per second.

(And the image of the camera manual above the cited sentence is owned/copyrighted by "ARRI AG" of Munich, Germany, not "Apple Films Limited".)

(I've worked with and researched Arriflex cameras from about 1987 to 2006 and own an Arriflex 16-M camera.)

Thank you!

You're probably right re the run time on the 400 ft magazines. That came from Les Parrot himself, who was the camera assistant and second camera operator on the film. He said they went through 80 reels of film, through the whole project.

And thanks for the I.D. of the ARRI camera image - that had also come to us from Les.

It's fascinating how Let It Be captured the tension and final days of The Beatles, while Peter Jackson's Get Back completely reframes that same period with a more intimate, nuanced view. Seeing their creative process up close—the laughs, the arguments, and the magic of songwriting—is a rare gift for any music lover. Jackson really gave fans a chance to appreciate how human and collaborative their genius truly was. It’s not just history—it’s a living, breathing portrait of art in the making.game is a fun like this

This behind-the-scenes look at Let It Be’s post-production is absolutely fascinating. It’s amazing how much of the final film was shaped by improvisation and instinct, especially given the syncing challenges and the evolving direction. The editing team really had to treat it like assembling a puzzle with missing pieces — a true creative process under pressure. It reminds me of how gameplay mechanics are fine-tuned in indie titles, where developers tweak and adjust in real-time just to make it feel right — similar to how we see things evolve in thegamespike. Sometimes the raw, imperfect process is what gives a project its unique edge.