The Making of The Beatles' Let It Be and Peter Jackson's Get Back The Rooftop

As things were progressing – and progressing well – at Apple, things were shifting from rehearsing for a concert that now wasn't going to happen to simply recording. . . or just more rehearsing. Lindsay-Hogg began to think, "The Rolling Stones Rock and Roll Circus was slowly unraveling, and I didn't want the same thing to happen to this. I knew we had a lot of interesting stuff, but they weren't thinking of any kind of extravaganza anymore. The special was done with. They were on to the music. And it was my job, as the person they'd hired, to figure out what to do next."

On the sixth day at Apple, Saturday January 25, just before lunch, he began thinking, "We needed somewhere to end this episode in their lives, which wouldn't be just another rehearsal of a song, which we'd done a lot. I knew we had to have some kind of climax for this weird little project. We didn't go to an amphitheater in Libya, we didn't go to the Roundhouse Theatre. There must be some way of getting them together, as a band, to play songs to an audience. So I thought, like a 1938 Mickey Rooney picture, 'Hey, kids, we've got the roof – let's go up and do it there!'"

He pitched the idea to them at lunch, waiting for the right moment. "I said, 'Why don't we just do it on the roof.' And John said, 'Do what on the roof?' And I said, 'A concert. Because we need some kind of conclusion to this thing."

So after lunch, a little "recon" visit was made to the rooftop, with Paul, Ringo, Michael, Glyn, and Richmond, Parrott and Bond, scoping out the landscape (with Russell photographing the visit for posterity). Lindsay-Hogg reviewed in terms of imagery. "I'm looking at what we'll use as a background to them playing, and access points where people might come up on the other roofs and be our extras – which is what happened," he says. Parrott brought one of the ARRI BLs, "Just viewfinding, to see where and that we could do, and doing camera spotting – to pick spots, as well as grab a little footage of the meeting," he explains. He, Richmond and their director then sat down and discussed how many cameras would be needed and planned their placement, 11 being the final number.

A helicopter was considered briefly, Parrott recalls. "A girl in accounting had an uncle who owned the largest private fleet of commercial helicopters in Britain," but its use was ruled out, due to minimum height restrictions when flying over London. "We were going to get one, but we couldn't fly low enough," states Richmond. "We would have been able to see the roof, see down into the street, but it was given the kibosh."

The 18th century building's roof was not built to sustain the loud of heavy amplifiers, motion picture equipment and a big load of people, so a contractor was brought in on Monday to determine if that was indeed the case and what could be done about it. A short scaffolding system, including a front railing, was built over the front half of the roof, where the load would take place, on which wood planks were placed, to use as a deck to support the musicians and crew. Notes Lindsay-Hogg, "Even though they hadn't fully agreed to do the concert, that had to happen. It wasn't expensive, and if it didn't happen, then someone would just take it down."

In addition, the contractor determined that the structure should be supported from beneath. Chris O'Dell worked as Apple A & R man Peter Asher's (of Peter & Gordon – and future Grammy-winning record producer for James Taylor, Linda Ronstadt and many others) assistant. "Our office was on the 5th floor, a little further back," she recalls. "There was a lot of activity for a couple of days – I couldn't see directly out of the office, but I could hear people going up and down, putting the roof support together. It was directly over Apple Music Publishing, which was at the front of the building, and where the stair access was to the roof, so they built that additional support there."

The contractor was also tasked with building a lobby hide, in which to place a "hidden" camera, facing the front door. It was anticipated – and, per Lindsay-Hogg, hoped – that the police, whose nearby substation was a block away, would likely be called to answer complaints about the noise of loud rock and roll playing in tony Saville Row. So a small structure was built behind the receptionist's desk, to house a camera, tripod, and operator Ray Andrews and his focus puller, complete with a two-way mirror. "It was supposed to be hidden, but it was the biggest 'hide' you ever saw!" laughs Parrott. "It took up 3/4 of the room."

In fact, when the police finally did arrive – and finally made it past Jimmy The Doorman – the setup was beyond obvious. "The lead cop comes in," says Parrott, "and turns to the second cop with him and simply says 'Shtoom - camera," shtoom being an English slang expression for "Quiet - Let's not talk about this."

It was intended that the show would take place on Wednesday January 29, but was moved to the following day, Thursday January 30, due to weather concerns. That morning, Harrington, of course, was tasked with bringing The Beatles' equipment to the roof. It took him about 40 minutes to do so.

Saville Row had a small two-man elevator near the stairs at the front of the building, which Harrington used to bring each item, piece by piece, to the 5th floor (actually, called the "4th floor," with the building's 1st floor being referred to as the "Ground floor," and the 1st floor above it). "I couldn't actually get much in the lift, without overloading it," he says. "Because the Twin Reverbs were so heavy, I had to take one up at a time." He had to do so with care. "Peter Brown told me, 'Don't damage the building. And don't overload the lift.'"

The elevator, of course, didn't go to the roof itself. That was accessed by a small, narrow stair, there in Apple Publishing, which had 8 or 10 steps and a bannister. "It was so narrow, I couldn't get Paul's bass cabinet around the corner and over the bannister. And the same for Billy's Rhodes cabinet." He called down to Mal for help, but the two still couldn't make the turn. There was a skylight just behind Apple Publishing (seen in a photo of the recon visit). "We tried hauling it up through there, with Mal pulling on a rope and me pushing from below, but it still wouldn't fit by 1/2 an inch. So Mal told me to go get a screwdriver – we took the window apart, pulled up the equipment, and then put the window back."

The band was set up, left to right, with Billy at far left, near the stair, Paul next, Ringo behind, and then John and George, both with their Twin Reverbs. An additional keyboard, a Hohner Pianet (which had debuted at Twickenham), available as a spare, should the Rhodes fail, was set up behind George, along with a spare Twin Reverb, though neither was used.

As mentioned it was decided to use a total of 11 cameras to cover the event, and six of those were to be on the roof itself. All but three of the 11 were ARRI BLs, whose light weight made them perfect for operators dashing about, capturing footage handheld. But, as Lindsay-Hogg notes, "The irksome thing about shooting rock and roll in those days was the limited amount of shooting time you got, requiring constant reloads," the limits of the BL's 400 ft magazines – even with start-and-stop shooting – keeping that a constant. "As soon as they ran out," says Richmond, "an assistant would pull the magazine, unload it straightaway, and put on a fresh magazine."

The main cameras on the rooftop, though, were purposely chosen for their larger capacity magazines, which never required reloading. At the two corners, facing the band, were a pair of Auricon 600 PROs, which had 1200 ft. magazines. "It was the classic Auricon, but the 1200 ft loads were a special order from Samuelson's," says Parrott, who was tasked, as always, as an assistant, with ordering and organizing the gear and film. "That provides about an hour of filming," which worked fine, with the concert lasting just 43 minutes, and start-and-stop filming.

In the center was another camera with a large capacity magazine – a Mitchell 16mm, notable for its 3-phase power supply unit, always seen next to the camera.

Parrott and Bond were at Samuelson's until 1am the previous night, gathering the gear, after which they brought back to Apple and prepped them for the crews in another room in Apple's basement. "Tony had already decided who was going to be where. I color coded all the cameras and their accessories with colored tape, so that when the crews arrived, I could tell them, 'Okay, all the cameras with yellow tape go up to the roof, cameras with blue tape stay down here,' etc."

Having worked in the movie industry throughout the decade, Richmond knew all of London's top feature film camera operators, who happily agreed to work the day, along with assistants and others who worked for Samuelson's. On the left-hand Auricon, facing Paul, was Ronnie Taylor (assisted by Terry Winfield), and at the other corner, near George, was Australian, Mike Malloy (assisted by Gordon Clarke), who, the year before, had shot The Beatles' "Hey Bulldog"/'Lady Madonna" promo film. In the center, seen laying down, to get forward-facing images with the Mitchell, was Colin Corby (assisted by Nigel Cousins), a close friend of Richmond's to this day. (22 years later, Corby also operated on Lindsay-Hogg's feature film, The Object of Beauty.)

Operating a BL handheld, floating around the rooftop to get great close ups was another veteran, Mike Fox, seen in many of Ethan Russell's still photos, with his black-frame glasses. Similarly, Richmond himself operated a BL. "I was sometimes right underneath John, looking straight up at him," he states, or wherever his instincts took him. Paul Bond was also, on occasion, encouraged to get on a BL on a tripod, and grab some shots himself. "He was the loader," says the director, "and then Tony and I thought, 'Let's give him a little fun, and give him a camera and let him work up there.'"

Because the three main rooftop cameras were so close to the band, due to the shallow space available, they could never capture a wide shot. So the production was given permission/access from the owners of a building across the street, and another operator, Ronnie Fox-Rogers, was set up with a BL on a tripod. "Their rooftop was a little higher than Apple's," says the director, "so we could be across the road and looking down."

Parrott, Mike Delaney, and a third, unknown, operator were dispatched with BLs handheld, to cover the reaction on the street below, with recording done by a roving recordist. Delaney was actually located around the corner, filming people's thoughts as they heard the music bouncing around the buildings, while Parrott was immediately below, including covering the police, as they knock on Apple's front door (with the reaction on the inside shot by Ray Andrews, inside the hide).

For lighting, Richmond notes, "We didn't know what the weather was going to be like, so I put some lights in," four Mole-Richardson Molefay 9-light fixtures (known as "Mini Brutes") – three on the deck, facing the band, and one above, on the left. The lights, supplied by Lee Electric, drew so much power, about 6K Watts each, that Lee had to send one of its electricians, Danny Eccleston, to patch their power cables into the building's electrical mains in the basement. "They called up and said, 'We want an electrician – can you send Danny?'" he recalls. "I was young and had long hair, so I fit right in."

The wiring, along with audio cables, came up through a white hatch door, seen to the right of the door to the roof, avoiding having them run on the top stairs themselves.

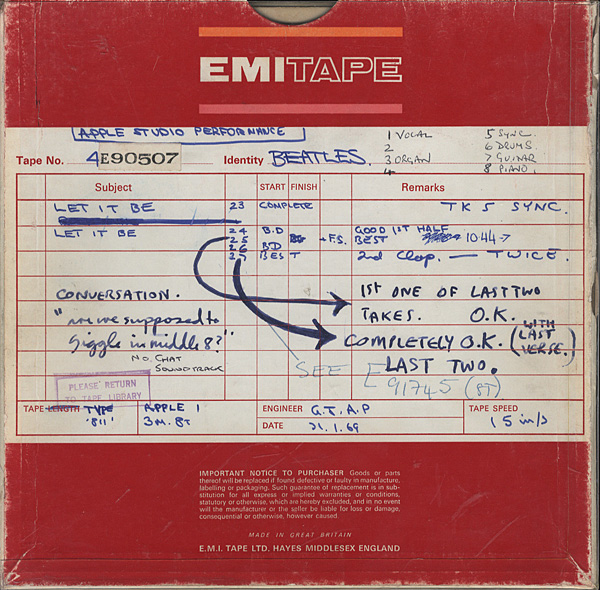

Having two engineers, Johns and Parsons, with plenty of "remote unit" experience – even if "remote" was just five stories upstairs – turned out to be fortuitous. "There was a stairwell down the middle of the building," says Johns. "So I could just run my cables straight down the stairwell from the roof." The engineer had done plenty of remote recordings, studio-trained at IBC to use their remote truck. "I was plenty adept at long cable runs." Thankfully, in this case, says Parsons, "EMI had a really good mobile unit, to record big halls and venues, putting a control room in another building," or, the basement, in this case. "So it had an enormous amount of long cables rolled up on drums, for that purpose. So it was pretty easy to run those cables down the stairwell to Glyn."

Parsons and Harries set up the mics, again using EMI's U67s on all the amps, and for Johns's drum miking (which also included an AKG C12 and a kick mic). And one was even set up in front of Paul, on a mic stand, in case he chose to play his acoustic guitar, which he did not. Harries made sure to pop up and check mics, at one point – "It was a cold, windy day, and they would do some retakes, so I'd just make sure everything was still on mic," he states.

It was windy indeed. With the AKC C30A longstem mics susceptible to wind noise, Keith Slaughter and Johns dispatched Parsons to get some material to act as a windscreen. "Glyn gave me a fiver," he remembers, "and said, 'Go out and buy some stockings.' So I went around the corner to Marks & Spencer on Regent Street, and went to the salesperson in the ladies hose department and said, 'I need a pair of stockings, please.' And the salesperson said, 'Yes, sir – what size?' And I just said, 'Oh, it doesn't matter.' So I think he thought I was going to go and rob a bank or that I was a cross-dresser!"

The EMI team also set up the two Vox PA columns, laid down in front of the band, to act as what would today be monitor "wedges," delivering a vocal-only mix to the band from Johns. Harries and Slaughter also brought up the Fender PA, its amp/mixer set up on top of a parapet, just next to the door, and its two speaker columns aimed down at the street, to deliver the band's full performance, thanks to a full mono mix from Johns and the REDD.51.

"You actually couldn't hear it very much on the street below," says Parrott. "But if you went 1/2 mile, two streets away, people were opening windows. You could hear it all over the West End." Though, per the main instigator, it was not loud enough. "I talked to George Martin about it," says Lindsay-Hogg. "The louder it was, the more people we'd get in the street. I wanted it to be heard over in Oxford Street. And he said, 'Yeah, yeah, we'll make it very loud.' But it didn't end up as loud as I wanted, because he was afraid of the speakers feeding back into the mics. So instead of getting 1000 people, we got 300. But we made it look bigger."

Interestingly, Peter Sutton also did recording on the roof, setting up his Nagra and mixer on the same parapet as the Fender PA amp (he can be seen with his gear, wearing headphones). He also had Roy Mingaye with him, with a shotgun mic in a Rycote suspension housing, standing near him. He appears to have been recording simply for camera reference, which he states at the beginning of the first Nagra rooftop reel, and his mix, upon listening, seems to have included both Mingaye's mic and Johns's full mono mix (since Mingaye's mic would have had a more localized pickup – mostly Paul and Billy – and the mix has the full band, the distant George plenty audible). His purpose was twofold: to provide a simple recording for camera reference, to be used for editing later. And since the multitude of cameras were not connected to his Nagra, providing a sync pulse, the Nagra, then, generated a sync tone, which was sent back to the control room, and recorded onto one of the spare tracks on Johns's 8-track – since only Johns's recordings would end up on the finished soundtrack, and needed to be able to be synced to camera, during the edit. (That setup was repeated the following day, in the basement shoot.)

During the show, Johns could use the Vox speakers for talkback, to communicate with the band – which he needed to, at one point, to let them know he needed to change tape reels, doing it himself, at about the 30 minute mark (the maximum for a reel running at 15 ips), during a break between songs.

Harrington, once things were set up and rolling, hung out off to the side, his next expected task being to break down the gear. But he was, famously, pulled into service in the middle of the show, as. . . a music stand. John had flubbed the lyrics on a take of "Don't Let Me Down," attempting to read them off the clipboard at his feet. So knowing the lyrically-complicated "Dig a Pony" was coming up, says Harrington, "He said, 'I need a music stand.' We didn't have one up there, so John just asked me to hold them up there for him. He wants a music stand, I'll be a music stand! What a Beatle wants, a Beatle gets."

(By the way, in his research for the film, Jackson and his team went to England and visited many of the locations where the film took place, including Twickenham and 3 Saville Row. "Peter would play back the original footage on his iPad and position himself, to get a sense of the camera's placement," Clare Olssen reveals. The trip also took them to Saville Row's rooftop. So. . . did Peter Jackson indeed kneel down in Kevin Harrington's position with his iPad, just as Kevin had done? Clare smiles, "Yes.")

As far as camera direction, while for Rock and Roll Circus Lindsay-Hogg was able to sit in a video truck and direct his DP and operators via mobile headsets, there was no such setup here. "And I couldn't have been speaking direction out loud into a mic anyway, because they were recording," he notes. So, similar to what went on at Twickenham, he and Richmond quickly developed hand signals that both could easily understand. "I didn't want, say, all the cameras on Paul, while he's singing a song. So if I crossed my arms, it meant cross-cut – one camera toward John and one toward Paul. Or if I held both hands facing out, forward, you'd have front angles of the two of them. And we always wanted to make sure someone had a wide shot.

"And Tony would communicate it to the operators. And, remember, these are professional, seasoned operators, who knew Tony from the feature world. They were alert guys, who were used to operating with one eye in the viewfinder and one eye looking for instruction."

One other person was behind a camera – Ethan Russell. "I was racing all around, climbing up high on either side, to get overall shots. And I couldn't get wide shots, with the four of them, because we were so close," even when positioned right up front, next to Colin Corby. "There's one shot, which the film camera got from across the street, where I've got one leg over the railing, and I'm leaning back, trying to get wide. If that railing hadn't been there, I could have gone over, down into the street."

The only audience – besides those who had come up onto their own adjacent roofs, as well as those working the production – was an audience of four: Yoko, Maureen Starkey (Ringo's wife), Chris O'Dell and Ken Mansfield, seated on a bench against a chimney, to George's left.

Though she had seen The Beatles at Dodger Stadium 2 ½ years earlier, Odell had a much more intimate experience on this day. She had arrived to work at Apple on May 17, 1968, a few weeks before The Beatles began working on The Beatles, and ended up working as Peter Asher's assistant, booking recording sessions for Apple artists, among other tasks. By this time, she and her colleagues were aware of The Beatles' activity downstairs, and, working the weekend, spent time either listening to music (Apple artist Jackie Lomax's upcoming album, she notes) and typing up lyrics for the band's use, brought upstairs by Mal.

On January 31, she, like all Apple employees, was disappointedly adhering to company orders, regarding visits to the roof. "We had been explicitly told that, as employees, we weren't allowed up there, because of the roof load concerns."

But over the past month, she had gotten to know Richmond, Johns, Russell and others, spending time together in the evenings. So that morning, when Richmond arrived, he stuck his head in her office. "He came in and said, 'Are you coming up?' and I said, 'No, we can't.' And he said, 'Yes, you can, because I need an 'assistant' up there.' So up I went!"

She split her time watching her employers play – to songs which, by this time, she had already gotten to know, from playbacks in Derek Taylor's office – to peeking over the side, to see how the people down below were reacting. "I do remember, it was so cold and windy, and just watching them playing and singing together as a band, under those conditions. But they were quite obviously having a great time."

As a Capitol Records executive, Ken Mansfield had first met and hung out with The Beatles during their 1965 tour. In 1968, after helping work out Capitol's distribution deal of Apple, he was invited over by Paul and UK label manager Ron Kass to manage the label in the States, based in the Capitol Tower.

His job regularly took him back and forth from L.A. to Saville Row – and on January 31, he. . . just happened to be there, sitting at his desk doing his job. "Mal had actually asked me, earlier on, to help scope out possible locations for the concert," which, of course, eventually didn't happen. "I was in the building, and Mal came in and said, 'Hey, we're going upstairs in 15 minutes – we're doing the concert."

Not wearing any real winter attire, he dashed downstairs to one of the tony Saville Row tailors and bought what appeared to be an overcoat, which happened to fit, and went up to the roof. "It turns out it was just a raincoat, and I was freezing."

During the show, Mansfield spent his time watching, or standing and chatting with Kevin Harrington. "I do remember one thing, because George's fingers were so cold. So before they started shooting, I lit up three or four cigarettes and put them between my fingers, so he could reach over and put the tips of his fingers close to the coals."

He did observe something in the band members he hadn't seen in quite some time. "Paul looked over at John, and John looked over at Paul, and they were in a groove. It was like they went, 'Yeah. This is us. This is who we are.' I was four feet from George, and just that look, you could see – they just turned and melted into the music." Adds O'Dell, "They 'passed the audition.'"

For the record, there was a moment, though, where the show almost didn't happen. They had committed the previous day to be out there at 12:30pm, says Lindsay-Hogg. "At about 12:15pm, the four of them and Yoko gathered in a little room under the stair that went to the roof. And that's when I realized, even though they were there, this wasn't a done deal. Paul said, 'C'mon, guys, let's do it. I'll be fun. We need to do something," but Ringo was saying, 'It's cold,' and it was only 46 degrees up there. George was going, 'What's the point, Why are we doing this?' There was a silence, with everyone standing there, and then John said, 'Fuck it – let's do it.' And up they went."

After the concert, the group went down into a room in the office and relaxed, before heading down to the studio to hear a playback with Glyn. "There was a great sense of relief," the director notes. "There was a great weight off their shoulders." After picking up camera gear, says Parrott, "I ran across George, who asked me, 'How do you think it went?' And I said, 'Well, I think people in the office building half a mile away heard you more than the people in the street.' And he said, 'Well, we weren't doing it for them. That's what they don't realize. We were doing it for ourselves.'"

The following morning, the band and crew returned to the basement studio to film the three songs which could not be played on the roof – the two piano ballads, "Let It Be" and "The Long and Winding Road," and the acoustic "Two of Us." "We knew what we were going to do. And there was almost like an 'end of school term' feeling," Lindsay-Hogg says. "Everyone felt, 'Oh, we're almost done with this now.'"

Also returning were two of the rooftop cameras, the Mitchell, which was set up at the piano, facing Paul, and one of the Auricons, set up to the left, capturing John, seated on the floor. Richmond and Lindsay-Hogg decided to make it a three-camera shoot, so Colin Corby was asked to return to operate, with sometimes the director himself manning an ARRI BL, shooting across to capture Ringo and Paul in profile, at the piano.

"Tony and I had talked about this," says the director. "I wanted all of the songs to be a mini-performance – complete, with no false starts. I wanted the ballads to be like ballads." Paul's two pieces at the piano were especially poignant. "They were very personal songs. So I wanted them to be really simple, and make him look as good as he did on that day, give him a relationship with the camera."

For "Two of Us," the setup was changed to have the Auricon capture a master, with Paul standing with his guitar at the mic, John in the lower right of the frame, on the floor, playing and singing, and the other two behind, with the BL getting closeups. "I changed the lighting, keying Paul on his left side, and keying Ringo his right," explains the DP. Curiously, most fans never saw John sitting there, either in the theater or, worse, on home video later. With the shift from 16mm, with its 4:3 square frame, to a 1.85:1 rectangular frame for the theater, the image was cropped, top and bottom. That theatrical image was then cropped again, left and right, when the home video release was prepared in 1981, when it was first released by Magnetic Video, losing even more of the frame. "In those days, it was easier to go from the 1.85:1 theatrical, rather than go back to the 4:3 camera negative," Parrott explains.

At the end of "Winding Road," the camera pulls back to reveal Richmond, leaning over the piano. "I thought that would be a nice little ending," says Lindsay-Hogg. "He's looking at the light, he's looking at Paul. He's going on with business. So it's as if to say, 'It still is a movie we're making.'"

With that, filming on Let It Be wrapped.