The Making of The Beatles' Let It Be and Peter Jackson's Get Back Filming Let It Be

The original film – as does Peter Jackson's – opens with Mal Evans and his 19-year-old red-haired protégé, Kevin Harrington, setting up The Beatles' gear at Twickenham in the morning of January 2. Harrington had started as a younger teen, working at their late manager, Brian Epstein's, NEMS office, moving on to Apple when the Fabs opened their own office in 1968.

It was during that time, around May, that Evans asked him a very important question. "He asked me, 'Do you want to come down and look after the band's gear?' I immediately said 'Yes,'" he recalls. "Cause I was an office boy. So one day I'm an office boy, and the next day, I'm The Beatles' equipment manager."

Harrington looked after the band's instruments all throughout the recording of The Beatles that year. "Mal showed me exactly what needed doing – changing strings, setting up Ringo's drums and buying drum sticks, strings and plectrums [picks]," at their favorite music shop, Sound City. "Once he'd showed me what to do, it took me about a week or two to feel comfortable being in the studio."

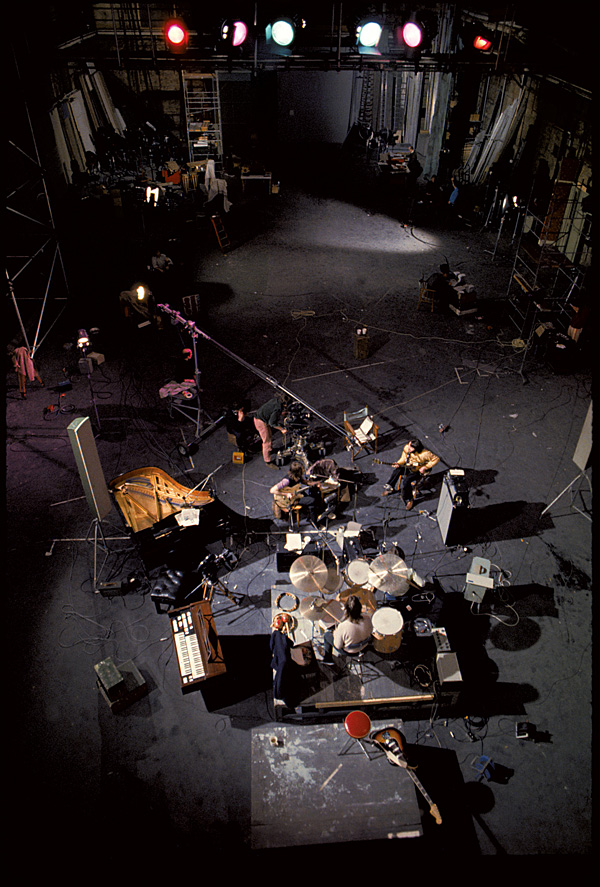

He got the heads-up call from Mal about five days prior to the start at Twickenham. On the morning of January 2, they brought the band's gear, and set up at the far end of Stage 1, setting up the instruments around a drum platform already constructed, to allow Ringo to be seen by the cameras, as he would be on a stage performance. The two then set up George's amp in front of Ringo, to his right, facing to the left, towards Paul's bass amp, which faced toward the center, and John's was set up behind George's, facing outward. To Ringo's left, forward, was a beautiful Bluthner grand piano, rented by Mal.

Fender, like many instrument manufacturers, were keen to have their products be seen being used by famous musicians, and had, in 1968, begun supplying them to The Beatles, who had, of course, used Vox guitar amps for five years. At the start of these sessions at Twickenham, they provided them with several Fender Twin Reverb guitar amps, as well as a Fender Bassman guitar amp & cabinet for Paul. (There were two Bassman cabinets available, one with 12" speakers and one with 15", which Paul received. The only way to tell them apart at the time was a "BASSMAN" sticker stuck on the cabinet – which Paul took a liking to, peeling it off and sticking it on his Hofner violin bass.)

They also had provided, the previous year, a Fender Bass VI – a 6-string guitar, tuned an octave below a standard guitar, making it playable as a bass, when needed. It was used a few times on The Beatles, and put to good use on these sessions, whenever Paul was playing a song on the piano, with John and George picking up bass duties for such songs.

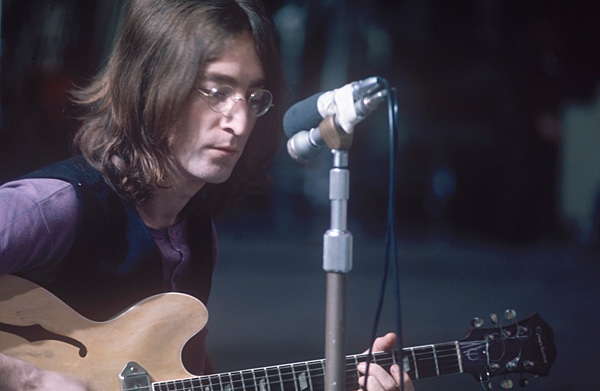

Besides playing his Epiphone Casino, John would occasionally take a spin on a Hofner Hawaiian Artist electric lap steel guitar, most notably on George's "For You Blue." George mostly played his 1957 Gibson Les Paul, known forever as "Lucy," a gift from Eric Clapton in 1968.

Ringo used his Ludwig Hollywood natural maple finish drum kit, which he had acquired from Drum City in September 1968, putting it to first use on The Beatles. The kit has two rack toms (8" and 9"), a 16" floor tom, and a 14"x22" kick drum. He stuck with his favorite Ludwig Jazz Festival snare drum, according to his longtime, current drum tech, Jeff Chonis. "To this day, Ringo and I call it the 'Let It Be' kit," he states.

As for that opening setup shot, with Mal carrying a "The Beatles" drum head, and him and Harrington pushing the piano, "That was staged," Harrington reveals. "Michael wanted an opening for the film, so he just said, 'Okay, Mal, Kevin, can you just move that piano from there to there. Oh, and can you carry something?'" Notes the director, "I just thought it would be an interesting opening, a low key opening, especially when it says 'The Beatles,' and Mal just tosses it on top of the piano. It sets the tone immediately."

To capture all of the activity, Richmond selected Arriflex (often called just "ARRI," by camera people) 16mm BL cameras, which were the main workhorse on Let it Be. Remember, at this point, what was being shot was a television special, not something ever expected to be shown in a theater, for which 35mm studio cameras would have been used. 16mm, with its 4:3 aspect ratio (which matched television screens then), was the appropriate choice. The cameras had 400 ft. film magazines, which ran for 21 minutes. "We were changing reels pretty often," states Les Parrott. "I think we went through about 80 rolls of film overall, which is a colossal amount of film, about 62 hours' worth."

The cameras came from ARRI with a standard Angenieux 10:1 zoom lens, "blimped" (enclosed in a housing to keep them silent), thus the "BL" in the model name. There were a handful of instances when Parrott would use an unblimped 8mm wide angle lens, typically when filming inside the Apple Studios control room, because of the small size of the room.

Coming from the feature film world, Richmond otherwise used feature gear, such as Moy geared camera heads atop the tripods the two used. "With a geared head, you could leave it on its own, because of its balance and weight," Parrott explains. "You didn't have to lock it off [tighten the camera head's movement knobs] to keep it in its position, versus a simple pan and tilt head. You could just come up and easily move it, if you wanted to adjust it." Richmond can also be seen at Twickenham with a U-shaped Lightweight ARRI head, designed for use with a common ARRI 2C pistol-grip camera, which would normally sit within the "U," but adapted here to allow the BL to sit atop it. There was also an Elemac dolly, an Italian dolly, which was often used on location work.

For film stock, Richmond again stuck with a trusted studio brand, Kodak, using their Eastmancolor Color Negative 7254 100T (in other words a film rated at ASA 100, and formulated for use with tungsten studio lighting, not daylight). In fact, for shooting outside – on the rooftop and on the street that day – camera operators would typically add a Tiffen Raton (85) filter, a tungsten-to-daylight conversion filter. "So every time you went outside," Parrott explains, "you had to put a Raton (85) filter on your lens."

All of the camera equipment and film came from Samuelson Film Service, at the time, known as the biggest camera supply house in the world, with whom Parrott, as a camera assistant, was plenty familiar. The company also could supply camera crew members. "The BBC and commercial TV companies didn't pay overtime, so their operators would get time off, in lieu of pay. So, on those days off, they would work for Samuelson's for other companies, as I often did."

A big part of a cinematographer's job is, not just camerawork, but lighting. Twickenham Stage 1 had a white cyclorama (or "cyc," as they are known simply), a white fabric backdrop which completely encircled the stage, and one which Richmond immediately took to lighting to give it character. "Tony and I used to drive in together," remembers Lindsay-Hogg, "and on the first day, he said, 'I'm not sure if we're spending a long time in Twickenham, if that grey cyc is gonna make everybody sick. I think we'll put some lights on it." Says Richmond, "It would have just been very boring, just against white the entire film."

While most documentaries would end up using smaller lighting instruments, such as, say, four "Red Heads" (small 800W red-shelled lights) and a pair of "blondies" (2000W cine lights), because they were in a film studio, Richmond had available traditional Fresnel movie lights, most of which were already up in the "grid," the rafters above the stage. "We had no resources at all, so we just made due with what was there," he says. There were five Twickenham staff electricians there, who manned the 5K (i.e. 5000 Watt) and 2K-sized Mole Richardson cinema lights, which Richmond had them add a different color each day. Notes the director, "And no one was tracking the color of the lights, for continuity's sake. There could be red behind Paul on one song, and green behind John on another. Tony was just painting the cyc."

He would also send Parrott up, 60 ft above the floor, to capture the look. "We had this thing – I'd go up there once or twice a day, climbing up to the lighting grid, three stories above them, and do a lock-off shot, to show the difference each day, as the lighting changed," he explains. Notes Richmond, "We shot so much footage, but we did need high shots every now and again, so we'd get him up there to do a high shot," Richmond says. "And he was younger than me, so he could climb the grid."

The approach to filming, at this point, was, in part, a bit up in the air, something which got figured out as things moved along. "You had to roll with it, with The Beatles, because things would change a lot," Lindsay-Hogg explains. "I was very aware of my role, in that they asked me to direct a TV special, and that's what I start out doing. And I tried to give them any ideas I had, and I tried to take on any ideas they had. And when they did, it was either, 'Yeah, well, that could be worked out really well" or 'I don't think that one's such a good idea. Let's. . .' It wasn't my job to roll over and play dead. My job was to try to come up with the best idea for them."

His job also wasn't to just become their friend. "A lot of people want to be participants, and to hang out. They wanted to be part of the circle. I didn't need that – I had a life at home. My role, as the director, was to be an observant and alert person, trying to figure out what was the best way to present these musicians. It's to be a collaborator, not be a groupie."

Between the two operators, there was no traditional "A Camera" and "B Camera," where "A" would get the most important images and "B" would pick up detail coverage. "Mostly," says the DP, "Les would be on a big setup in the back, behind them, and I would do handheld coverage, nearby them. And if I had a difficult shot and needed a focus puller, Les would leave his camera running on the tripod and come and pull focus for me."

If one spotted one of The Beatles doing something important to capture, he or Parrott would let the other know, or the director would do so. "If there was a conversation going on, we would signal, 'Let's try and get this conversation.'" Parrott says. "Tony or Michael would signal, like an 'over there' gesture, and you'd pan over to something that they'd picked up was happening." Notes Lindsay-Hogg, "Sometimes, if there was something going on, Tony and I would have eye communication with each other, and then I'd sort of point toward Ringo, and he'd start shooting it himself," or else signal to Paul Bond, who would tap on Parrott's shoulder and quickly relay the instruction. "There was a little silent semaphore thing going all the time," Parrott adds. And sometimes, if the others were busy or off at lunch, and Lindsay-Hogg noticed something important, he would pick up a camera and film it himself.

It was rare at Twickenham to capture whole song performances – something which would have a big effect on the edit later – mainly because there often were none. Says Parrott, "We shot whatever they did. And the times they would do a full runthrough at Twickenham was very few. Mostly, it was just playing around, putting up ideas. We didn't roll all the time – it just didn't seem to make much sense. That was rehearsal time."

"Sometimes, we would track a song from starting to rehearse," says Lindsay-Hogg, "like, 'Let It Be,' Paul would start to rehearse the song, and then stop in the middle, and they'll play Tamla Motown for half an hour. We were shooting from 10 or 11am until 6pm. If there wasn't much going on, we'd shut the cameras down for a while, and then just turn them on if something was happening. There wasn't much planning, but alertness was key, catching them when we realized something was happening."

On occasion, Lindsay-Hogg would get a sense something was up, and would deploy the cameras in a certain way, to allow a private conversation to take place without being disruptive. Such was the case, on Day 3, Monday January 6, when Paul and George are seen having their famous "If you want me to play, I'll play" conversation.

"I had a sense there was some tension between them," he recalls. "I knew there was some issue between the two of them, and I didn't want them not to be able to be candid with each other, because the cameras were right there. So I deployed the cameras in a different way, to be unobtrusive and a little bit away from them, so it wouldn't look like they were being spied on." Parrott was dispatched to the rafters, looking down towards Paul, and Richmond was on a tripod on the telephoto end of his zoom lens, to get the shot over Paul's shoulder toward George (which resulted in a bit of a fuzzy image, because of the low light level at that distance). Says Parrott, "We were doing a lot of that kind of telephoto work. So, many times, I could barely even hear what was being said."

Dailies were prepared each night by Technicolor London, whose plant was located alongside London Heathrow Airport, just a few miles from the studio, where they were delivered each morning for viewing in one of the studio's screening rooms. "Don't forget," notes the director, "dailies on two cameras, per day, is a lot of time," done mostly before The Beatles' arrival each morning, at one of the screening rooms at Twickenham's post production department.

One thing, though, which made preparation of dailies difficult – and which would carry into not only the production of Let It Be, but to Peter Jackson's Get Back – was syncing audio to picture. In typical film production, a camera assistant will snap a clapperboard in front of each camera's lens, to produce both a physical, visual instance and a sound, on the tape, to line the film and recording up together. Here, though, because filming took place often on the fly, with Sutton continuously rolling audio, the two camera operators often didn't have time to use a clapperboard (which also would have made a sound, which would have been disruptive to The Beatles' music performance). "Initially," says Parrott, "We worked out with Peter that we would pan around to him, and he'd have a clapperboard, near his Nagra," marked with the film roll ID. "But, in the end, we stopped bothering with sync. Occasionally, if there was a really long conversation bit, I'd signal to Peter, and I'd pan over, and we'd get a clap for that piece. But they were few and far between."

"We tried to slate," says Lindsay-Hogg, "but a lot of times, the cameras would just start to shoot, because something was happening, and we didn't slate it. Slating was sometimes a luxury."

And that resulted in havoc, each day, for the editorial assistant, Jimmy Rodden, tasked with syncing the dailies. The film's editor, Tony Lenny, and his assistant, Graham Gilding, knew Rodden from their feature work. "He wasn't doing anything," Gilding remembers, "and we said, 'Do you want a real boring job, and come in and sync these rushes?' And he said, 'Yeah, okay.'" Without the benefit of proper slating, he says, "Jimmy was having to do it by sight, looking for a handclap or somebody picking up a guitar. He matched it all by eye," sometimes resulting in dailies coming. . . two days later, not overnight. "If we wanted to do two hours of dailies," says Lindsay-Hogg, "we'd maybe only do an hour, cause the rest weren't synced up yet."

Interestingly, notes Jackson's talented Get Back film editor, Jabez Olssen, the cameras were actually delivering what's known as a "sync pulse" signal to Sutton's Nagra machines, through a cable connection, which kept both camera and recorder running at the exact same speed. The signal from Richmond's "A Camera" went to Sutton's "A" Nagra, while that from Parrott's "B Camera" went to the "B" Nagra. "Every time a frame was exposed on the camera," Olssen explains, "an electrical pulse was sent to the Nagra, and recorded onto its second track," with the audio being recorded onto the first. One problem, though, was that Sutton, as described earlier, ran his Nagras in overlap – they typically weren't both running. So even though Parrott might be shooting, the signal from his camera wasn't recorded anywhere, since the B Nagra might not be running, only the A Nagra was. So not much help for poor Jimmy.

Things moved along through the second week, with George becoming more and more frustrated with how introductions of his new songs were never taken seriously, and, with what appears to have been some building mistreatment from John, on Friday January 10, he decided to leave – not just the studio, but leave the band.

"I remember very clearly," says Glyn Johns, "when the disagreement happened on the soundstage between George and the rest of the band, we felt we should leave. It was none of my business. And I do remember – it was raining, in January, a cold, horrible day – sitting outside the soundstage with Denis O'Dell, going, 'Well, fuck me – we've waited all this time, to be able to work with them, and it lasted five minutes. What a drag.'" It wasn't the first time he'd seen it happen. "At that point, I'd worked with loads of different bands, and it was nothing unusual. In a group of people, particularly in a creative one, it's quite normal for somebody to go off on one or to be unhappy about the way things are going. It was rather sad, but I didn't think it was unusual. I'd seen it a hundred times, and probably will again."

As for how that affected production, when work resumed the following Monday, of course, it was just the three of them, and, of course, not much got done. "Suddenly," Parrott recalls, "they just said, 'George has gone home to see his mom.' That's what we were told." Notes Lindsay-Hogg, "It was kind of hush hush. Only because the other three didn't really know how to process it. So there were two scenarios – one which those of us who were in the Beatle group knew, and other guys, who they didn't think need to know. Cause they figured it would work out, although they didn't know how."

Eventually, says Parrott, "They said, 'Okay, we're just calling a halt for the moment. We'll just wrap everything,' and we basically wrapped up the gear, and I went home."