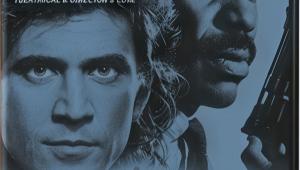

Blade Runner: How Great HD is Made

On the Warner Bros. Studios backlot in Burbank, California - a couple of "streets" away from the modest Victorian clapboard house of James Dean's teenhood in Rebel Without a Cause and just around the corner from the back emergency-room entrance to TV's ER - there's a quaint- looking building that once served as the exterior of the Yukon Hotel visited by Deckard (Harrison Ford) in the movie Blade Runner. The front has made appearances in other films and TV shows since then; and for each of those appearances, the place has been changed, refurbished, and dressed up.

Blade Runner itself has undergone a number of transformations since it came out in 1982. Aside from the different versions - this fall's Blade Runner: The Final Cut being the latest - the sci-fi classic has also lived on in different mediums, from film to VHS to laserdisc to DVD. Now, this restored "final" director's cut is getting a video-resolution upgrade, making its debut in high-definition on Blu-ray Disc and HD DVD.

Since the recent advent of high-def discs (and even, really, of DVDs), Warner Bros. has had a great track record of transferring titles with the best possible visual and audio fidelity. In a word, Warner Bros. discs often look pristine. And keep in mind that just because a movie is in high-def is no guarantee it will look great; an HD transfer can suffer from poor compression, bad color, weak contrast, dust and scratches - you name it. (Note the huge disparity in image quality of the high-def movies playing on cable.)

"Studios do have technical differences in their mastering and compression approaches," notes DTS Digital Cinema's chief technology officer, John Lowry - the man who's done stunning restorations of the James Bond series, some classic musicals and Alfred Hitchcock films, and the initial Star Wars trilogy. "Perhaps the biggest differences are in their image-quality goals for their high-definition masters. A year ago, many studios didn't recognize they had a problem. They'd been mastering in HD and approving those masters looking at a CRT-based monitor displaying uncompressed data. Today, they recognize that the consumer is viewing the images on large, bright, high-contrast HDTVs after compression and decompression."

So what's the secret to making great HD? Warner Bros. is as good a studio as any to show us the recipe, so S&V invited itself into the WB kitchen, so to speak. On a perfect October day, the studio had me out to its production facilities, just a short walk from that hotel where Deckard sought clues to track down a replicant. (Click on image above to see gallery.)

The Translators Among the clatter of chatter, plates, and silverware in the Warner Bros. executive commissary, Chris Cookson, the company's president of technical operations, and Ned Price, vice president of mastering, explain the studio's approach to mastering high-def discs.

"Certain changes have to be made as you go from theatrical to TV, to make up for the fact that the technology is different," Cookson says. "That's what predominantly oversees the translations." Adds Price, "You have to adapt the theatrical intention - the way it appears in the theater - to the home-video medium."

Later, I speak with WB vice president of post production Kurt Galveo, who took a hands-on role in the transformation of Blade Runner to high-def disc. "We wanted to make sure that no matter what platform you look at it on, you always see the same thing," says Galveo. "We try to match the warmth, color, and texture. To keep that same kind of image on video, there are adjustments you have to make in color, because electronically it's a different color space. Plus, sometimes you have to add grain. When we scan the image and put it on digital form on disc, it can be too clean; you have to add texture so it looks like people remember it from the theater. But sometimes you literally have areas in the film where there's too much grain - opticals [special effects], for instance, can actually introduce more grain - so we have to take some out. It goes both ways."

And there's even more knob-turning required. "You do have to adjust contrast," Galveo continues. "It depends on how the scene was shot and lit. Also, compression can change what the blacks look like. Electronic blacks and film blacks look very different. You have to balance it out so it looks like the original."

Aside from the tinkering required to make video simulate film, the restoration magicians used a lot of elbow grease to bring Blade Runner up to high-def snuff. "We had to do multiple, multiple passes on the negatives - four or five times - dust-busting them and cleaning them," Galveo recalls. "Physically, all the negatives were in good shape. But some were filthy. In the old VHS days, when the detail wasn't quite there, it was a little more forgiving. But now the home viewer with HD has much higher-quality resolution to view a film, so we have to keep cleaning this until we see no dirt whatsoever. We content providers have to put more TLC into a project so the final product that the viewer takes home looks as good as can be."

Everything's Gonna Be 4K My feet are sticking to the floor. Is this what the WB VPs meant when they said they're trying to reproduce the movie theater experience in high-def? Actually, I'm entering the 4K scanning room in Warner Bros.' Building 38: Motion Picture Imaging. The glue under my shoes is a mat that's supposed to remove dirt and dust from my under-person. The rest of me gets draped in a mandatory lab coat - again, to create a more sterile environment.