Wow, I learned so much by reading this. Already having seen the Jackson film I must simply now watch it again with new knowledge. Perhaps because of time and the scant often poor quality of old Beatles live performances it is overlooked what a fantastic, compelling, and potent band The Beatles were live. I think this new Jackson film sets makes the case that the studio wunderkinds were also one hellacious live band. It is indeed poignant that the rooftop concert was the last time time they performed live. One can imagine that if the breakup did not happen and The Beatles continued they may have resumed proper concerts. Obviously they very much enjoyed playing together for a live audience.

The Making of The Beatles' Let It Be and Peter Jackson's Get Back The Production Team

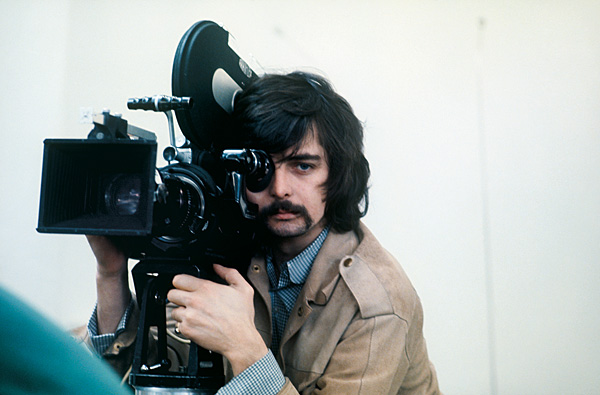

Tony Richmond got his start in the film business in 1960, as a teenager, working in the camera dept. as a focus puller (sometimes called a "clapper/loader" – loading film into motion picture camera film magazines and marking/snapping the clapper board, at the start of takes – eventually moving up from, in American camera lingo, a "2nd" to a "1st Assistant Camera" (1st AC)). Among others, he worked such huge David Lean projects as Dr. Zhivago, a job that lasted 52 weeks.

Director John Schlesinger filmed Far From the Madding Crowd in summer 1966 with director of photography (DP) Nicolas Roeg, with Richmond working as a focus puller, and in early 1967, when Schlesinger needed some additional shots, he found Roeg unavailable, in California, shooting Dick Lester's Petulia. "I couldn't go with Nick, because of union rules, and John said, 'Listen, we need some extra shots, and I want you to come and do them for me,'" Richmond recalls. In October that year, when director Basil Reardon was looking for a DP for his David Hemmings crime comedy, Only When I Larf, Schlesinger recommended Richmond. "I became a DP on a major film at age 24. It was unheard of," especially making the jump right from AC to DP, without becoming an operator first – something the establishment in the industry didn't look kindly upon.

"The old guarde treated him with a certain scorn," notes one of his ACs at the time, Les Parrott, who met Richmond on a half hour short film project and continued with him. "But he had balls the size of Albert Hall. He wasn't afraid of anything."

Six months later, in May 1968, a title company asked Richmond to come back and shoot the title sequence for Larf, which featured the film's cast. "And they were pushing Michael Lindsay-Hogg, who was one of their directors, to direct it," he recalls. "We did three days shooting, and Michael and I became great buddies. We both liked the glass of cognac and smoking cigars. And at the end of it, he said, 'What are you doing next Saturday?' I said, 'Nothing.' He said, "You want to come and shoot something with me for The Rolling Stones?' That was 'Jumpin Jack Flash,' and it was the first rock and roll thing I ever shot."

"I'd seen him around London, because we were both young and moderately successful," and both part of the hip London rock and roll scene, the director remembers. "And to be young and moderately successful, in those days, was unusual."

The two shot another promo film for the Stones, "Child of the Moon," the following day, continuing to work together, and then in December, Lindsay-Hogg enlisted Richmond to film The Rolling Stones Rock and Roll Circus, using a novel camera system Mick Jagger had spotted in France, which had a combined video and film camera system in one unit, allowing Lindsay-Hogg to direct from a truck outside, via video, while the cameras captured the players on film. "I had kind of a rough time on that show," the DP recalls. "I had television camera operators, instead of film camera operators, and looked at me as just a lighting engineer. They didn't like me telling them where to put the camera."

Not long after, when Lindsay-Hogg asked him to join him doing The Beatles' live concert show – on videotape – "I said, 'I don't want to do it.' I didn't want to go through that again.'" A week later, though, Richmond's friend, Denis O'Dell, with whom he'd worked on a number of films, rang him. "He said, 'Listen – the boys have rented a stage at Twickenham to rehearse this spectacular they're doing. Why don't you get a couple of cameras and a couple of guys, and come down and shoot what you can.' That was a separate thing. So I brought two of my assistants, Les Parrott and Paul Bond, and I bumped Les up to operator to shoot alongside me."

25 year old Les Parrott had been a freelance AC, before beginning working for Richmond in 1967. He not only assisted on "Jumpin' Jack Flash," but also The Stones' One Plus One, directed by Jean-Luc Goddard, showing the group at work at Olympic Studios recording "Sympathy for the Devil."

On the sound side, Richmond recommended to O'Dell Peter Sutton, an experienced production sound mixer with whom he had worked on several films, to record at Twickenham. "Peter was a very accomplished, quiet mixer," Parrott states. "He knew how to work any scene to get sound, and he was very good at 'eavesdropping,' slipping in a subtle mic, just in case," something which would indeed come in handy on this project. Adds Lindsay-Hogg, "He was very calm, low key – he wasn't frantic. Just a very solid technician."

Sutton's team included boom operator Roy Mingaye and "sound maintenance man" Ken Reynolds, who essentially stood by Sutton and kept records of the recording reels (and occasionally operated a second boom, if needed). "In the 60s, England's film industry was totally union-dominated," Parrott explains. "In 1955, say, you'd have to have a recordist, a boom swinger, a maintenance man and the sound camera operator," the latter when film audio was still recorded to 35mm magnetic or optical film. "It wasn't until the late 60s, a few years after Nagras came out, that there were less, but even then, legally, sound crews had to have three people." Even the camera team normally would be required to have four members, "But we got away with three, because we were deemed a documentary."

The aforementioned Nagra was the recording machine which became the standard for film recording, until only recently, when superseded by digital recording devices. Sutton recorded with a pair of Nagra Model IV recorders, set up to record in overlap – each receiving the same mono signal from his Nagra BM II 4-channel mixer, with the "B" machine started recording a minute or two before the 4-inch, 16 minute tape on his "A" machine was due to run out, allowing a continuous recording. (Fans aware of the famed "Nagra reel" bootlegs of these recordings, which were stolen by an Apple staffer a year or so after the film was completed, and recovered only as recently as 2003, often mistake the two sets of reels as somehow having one set of reels associated with Richmond's "A" camera and the other with Parrott's "B." With one rare exception, noted below, the content on both reels represents a single mix/recording.) Sutton was set up about 20 or 30 feet back from the band, midway from the large stage door, on a small table.

Sutton used four AKG D25 dynamic microphones (herein referred to as "discussion mics") – he had four inputs available on his mixer – distinguished by their notable spring shock mounts, suspending the diaphragm from a metal ring. Three were mounted on simple vertical mic stands, and the fourth was used by Mingaye on a standard J.L. Fisher studio boom. At Twickenham, he placed one between Paul and George, to pick up their conversation and amp output, another by John, and a third over by the piano, picking up Paul's playing and singing there.

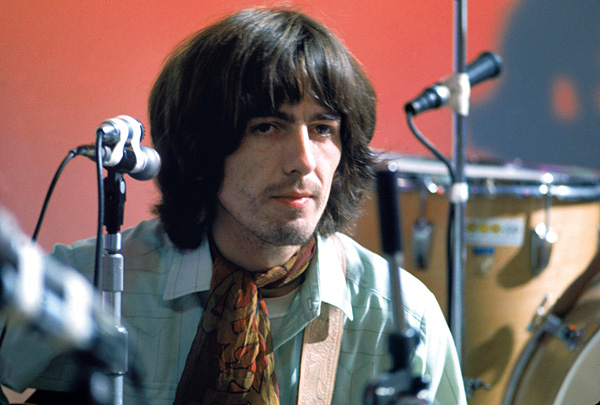

The Beatles were used to working in a recording studio, where they wore headphones with an appropriately-balanced monitor mix. But since headphones weren't attractive to the camera, they didn't use any, either at Twickenham or at Apple, But within the first day, the band noticed that they weren't able to hear their singing above their playing, so George can be heard requesting a PA system be brought in, to help with the problem.

The request would have gone to producer O'Dell, says Lindsay-Hogg, who would have then asked longtime roadie Mal Evans to arrange. Mal, then, called over to EMI Studios at Abbey Road, and requested assistance with the matter. Responding were two of the studio's seasoned technical engineers, Dave Harries and Keith Slaughter. Harries had joined EMI in 1965, working first at the company's Tape Records division over at their Hayes factory on Blithe Road, before getting word from the studio's tech engineer Peter Lindsey that he was leaving, and suggested Harries apply. "I applied, and I got in," Harries states.

"We got a call that The Beatles were rehearsing at Twickenham Studios, and that they needed a PA system and some mics," he recalls. So he and Slaughter brought a nice collection of AKG D19 dynamic mics, mic stands and cables. "We didn't take any condenser mics," which The Beatles were used to using, "because it wasn't meant for recording – just as a PA." They connected the mics to an unknown PA mixer owned by the studio, which was set up on the back right corner of Ringo's drum riser and connected to a pair of Twickenham's column speakers. "We didn't have anything like that at Abbey Road." The microphones were set up solely for vocals – the instruments/amps, set up in close quarters to the group, didn't require being piped into the PA.

Harries and Slaughter stayed on throughout the group's stay at Twickenham, available, as needed. "Of course, we were very naughty boys, because we were 'sound people in the record industry, and everybody at Twickenham was in the film union," Harries notes. "They used to take the piss out of us a bit," someone occasionally coming in and shouting, "Right – well, let's have a [union] card show then!" which the EMI fellas, of course, didn't have. "I actually had some cables running across the car park, and when I went to move them, I wasn't allowed! One of the riggers had to move it all."

After a day of work, Sutton realized that he wasn't able to get a clear vocal recording using his current microphone setup, the mics picking up a combination of instruments and vocals. So for Friday January 3 and part of the day Monday January 6, he attempted to record in a different manner. He taped some STC 4037C microphones to EMI's D19s, and ran them through a second Nagra mixer, recording the content from the D25 mics to the "A" machine and the vocals to the "B" machine. Notes Brent Burge, who would work with the recordings while constructing the soundtrack to Jackson's Get Back, "There's a chunk of Day 2, where we found we've actually got two different recordings. But then, I think he figured out that if he kept doing what he was doing, they would miss a lot. Plus, there was no way to sync the two reels to make a single recording. So he went back to just doing overlaps," which continued for the remainder of the shoot. "There was so much organically going on, that they were just trying to find their way."

Sutton typically ran the Nagra even when the cameras weren't rolling. There is 60 hours of footage, but 160 hours of Nagra recordings. "Peter's thinking was that we might conceivably use some of that material for voice over, as linking," says the director. "So he'd want to give us all that he could give us."

There was one instance where Lindsay-Hogg, though, specifically requested a recording – Friday January 10, the day George quit the band. "I had a sense there was some tension between them all. And John and Paul considered George the junior songwriter, and he knew he was very good and was about to blossom. And I had a sense there was growing frustration, and I thought some of this might come out at lunchtime. So I asked Peter to put a mic in the little pot of flowers that we had on our table, where we ate lunch."

Twickenham had a separate small, white-walled building with many windows, just to the west and back of the soundstage, which had a small restaurant upstairs, as well as a bar, which one would enter first. "They had a kind of a canteen for the working guys, who would drink beer before lunch – or for lunch," he describes. Partitioned off from it, somewhat hidden, was an area where there were a few tables where The Beatles (with Yoko), the director and Richmond would typically have lunch each day, along with a few executives and actors, who could order hot meals from the kitchen.

On this day, sensing something was up, Lindsay-Hogg asked Sutton to hide a microphone in the flowerpot, wrapping a piece of tablecloth around the wire, which led away to a separate Nagra machine, likely in the nearby pantry. "George didn't join us for lunch, like he usually did. But he came up about 10 minutes later and stood at the end of the table and said, 'Seeya round the clubs' – meaning, 'I'll see you in the clubs and restaurants, but I'm gone.'" The conversation did get recorded, but, upon listening, he notes, "When I played back the flowerpot bug, all I could hear was the clatter of cutlery!" A further, important discussion between John and Paul, regarding the situation, was recorded in the same manner on Monday, January 13, and appears in Get Back's Part 2.

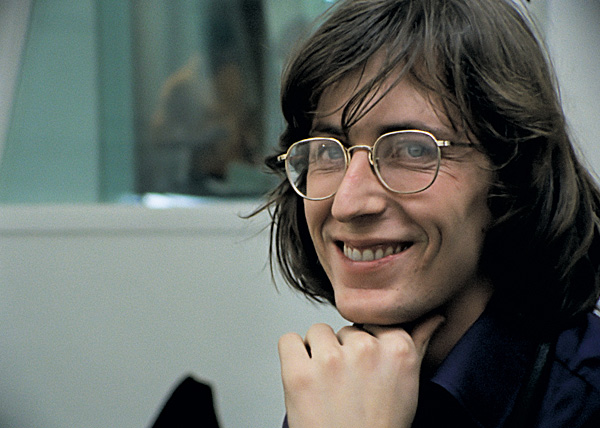

There was another very important sound person present at Twickenham. Glyn Johns had started his career in recording as an engineer at IBC Studios, recording bands such as The Who, The Kinks and countless others. In 1967, he became the very first freelance engineer, and recorded many key records for The Rolling Stones and others out of his home base at Olympic Studios in Barnes, London. "He was the go-to engineer at the time," notes Lindsay-Hogg. "He'd been The Rolling Stones' guy as early as I knew them. When we were doing Ready, Steady, Go!, and we had live sound, when the Stones were on, he would come out with [their producer] Andrew Loog Oldham, to help get the mics right." He also happened to be present – though didn't engineer – at The Beatles' television special, Around The Beatles, in 1964. He would also track the recordings at Rolling Stones Rock and Roll Circus, his first-ever collaboration with a Beatle (John).

One night, in early December, he received a phone call from someone with a Liverpudlian accent, claiming to be Paul McCartney – Mick Jagger, perhaps. After spending a few minutes trying to get Mick to knock it off, he eventually realized it was indeed Paul. "He told me that their plan was to do a live concert of all new material, which he would like me to record," Johns recalls. "And he said they were going to begin rehearsing just after New Year's, and that he'd like me to attend the rehearsals, so I said, 'Okay.' I think Paul's idea for having me there during the rehearsals was just so that I'd familiarize myself with the material. And when I got there, they accepted me readily and were all very welcoming."

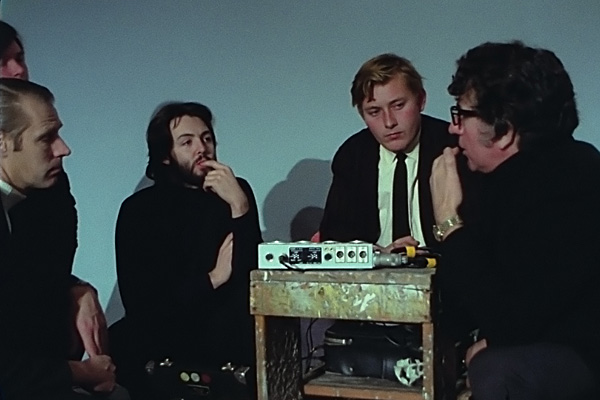

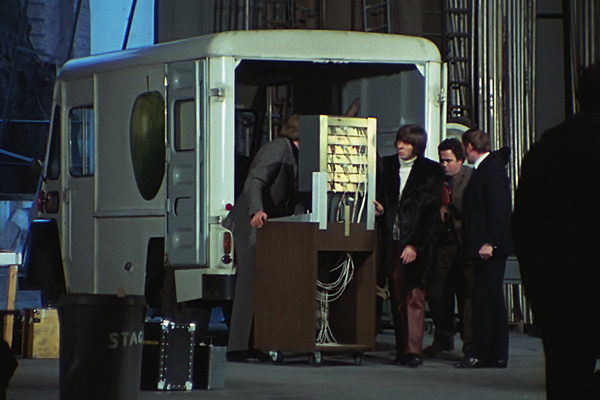

By the third day, Monday January 6, the band had decided they would like to be able to hear how they were doing, so George's 3M M23 8-track tape machine was brought to the studio in the Apple Electronics truck, by Mal Evans. The machine was placed in a room connected to the soundstage. "There was a funny little room with some equipment in it," Dave Harries remembers, located to the right (when facing the band), which had no windows into the stage. "It may have been off a corridor or maybe even a small studio or makeup room," Lindsay-Hogg suggests. Johns had some additional equipment brought in from IBC Studios, most importantly a United Audio 610 mixing console, made in the States by Bill Putnam. He would record their playing, and play back a mono mix, likely through an unusual speaker, possibly also brought from IBC, seen set up between George's position and Paul's bass amp (though Johns does not believe that was the case).

He began recording the following day, taping some additional STC 4037C mics, as Sutton had done, to the D19 PA vocal mics. Two unknown mics were set, using some of EMI's boom stands, on John's and George's guitar amps (Paul's bass amp was wired direct to the console, instead of miking the speaker cabinet, a practice which would continue at Apple). And Johns, again, using whatever mics were available, set up his novel drum miking setup, which he had recently developed, placing one microphone over the snare (in this case, an AKG D224E mic, which appears as a long shotgun mic) and an another microphone set at the floor tom, aiming across (here, another STC, taped to his right-hand cymbal stand), which, when spaced properly, created a perfect stereo drum image.

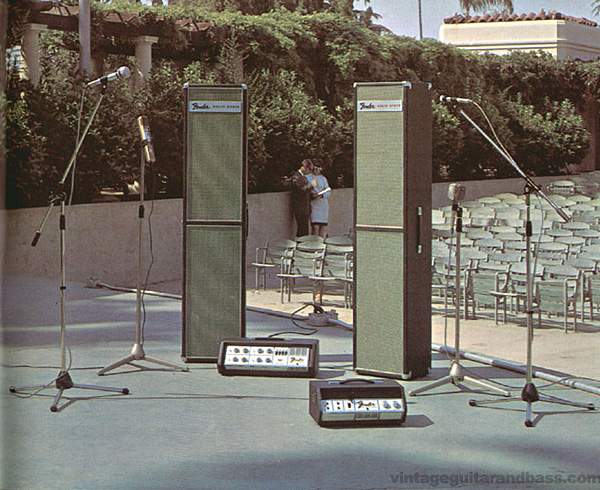

On Wednesday January 8, a new PA system was delivered, Fender's new solid state PA, with a pair of column speakers, which were set up facing the band. The dual miking (one for PA, one for recording) was replaced by single Shure SM57 dynamic microphones. These, apparently, possibly from then on, were used to provide a single signal to the console for each mic, with a mono mix created at Johns's console, going to the PA (though he could have simply recorded the mono mix to the 8-track – with the passage of time, neither Johns nor Harries recalls). The Fender PA would play an important role, too, with the move to Apple, and particularly on the Rooftop.

The recording reels for these recordings have never been found, the tape likely reused, since the recordings were strictly used for playback at the studio, and that was it.

Besides motion picture cameras, there were also a couple of still photographers present – the then-future Linda McCartney, of course, but also another, someone who would become a mainstay of iconic rock photography.

A San Francisco native, Ethan Russell had been an art major in college, and hoped to become a writer. He picked up his first camera, a Pentax SLR, while at school, and a photographer friend taught him how to develop black and white prints. "I wasn't a photographer. I had seen Blow Up, and thought, 'Oh, that looks fun,'" he recalls. But after doing what most SF kids did during the Haight-Ashbury period, his father queried, "Are you using your time as well as you might, son?" and promptly sent him to England in early 1968. Though he arrived knowing no one, he remembers, "I felt like I had been born there."

Having taken a few pics of his brother's band back home, he had a "portfolio" consisting of one photo. "So this guy said, 'Do you want to photograph my next interview?' I said, 'Sure,' and when I asked who it was, he said, 'Mick Jagger.'"

"The guy" was Rolling Stone's Jonathan Cott, who, in late August, invited Russell along to shoot an interview with. . . John, who opened his door and played them an acetate of a new Beatles recording – "Back in the USSR." Afterwards, John invited them to accompany him and Yoko to EMI, where recording of The Beatles was continuing, though, "I didn't go into the studio – I was scared." Nervous, he went into the studio's canteen, where Cott was interviewing Yoko, and he proceeded to take some beautiful shots of her. "And everybody flipped over them." He was then invited by John every so often to come to their apartment at Montague Square and take more – one of John actually ending up on the collage poster included with The Beatles. In mid-December, he was asked to shoot Rock and Roll Circus.

A few weeks later, on Friday January 3, Neil Aspinall, who had seen some of his John & Yoko photos, asked him to come to Apple, where Russell also brought his Circus photos. "He took a look at them and said, 'Oh you were taking pictures of those guys.'" Knowing the whole lot down at Twickenham – John, Michael L-H, Tony Richmond – Russell inquired about going down to visit them, but Aspinall responded, "No. Completely impossible," then, "He made something up, saying, 'David Bailey is down there!'" which he was not. "He said, 'You can't go down," so I just went down."

There was no security at Twickenham in those days, so, armed with a camera, he stood at the soundstage door and took a photograph. "I was standing there, just inside the door, and I turn – and there's Neil!" he recalls. "I felt his eyes on me." Making up something else, he says, Aspinall then told him they had decided they would like him to photograph the rehearsals – for a day. "I told him, 'I won't come down for a day – I want three days.'"

He arrived at the studio the following Monday January 6, armed with two cameras – a Nikon F, shooting color slide film (Type B Ektachrome), and a Nikkormat FT ("a funky little camera, I used forever") shooting black and white (Kodak Tri-X Pan ISO 1000).

Though, he notes, humbly, "I was barely a photographer at this point," Russell covered the rehearsals in the way he has always done since. "I would go in, pick a shot, and get out. I didn't hang out. Just get close enough to take those tight photos, and leave. And if I do it well, you just get them, not some fanciful nonsense. They're not packaging." He only took what he needed. "I would see contact sheets of other photographers, with 36 images on them – and 35 would be the same shot. If you look at my contact sheets, you get three shots."

For those keeping track, he shot on that Monday and the following day, Tuesday January 7. No photos were taken on Wednesday (the Get Back book features frame grabs from film footage for days when no photographer was present), and Linda shot on Thursday and Friday (the day George quit). He did shoot the following week, on Monday January 13 and Thursday January 16, as The Beatles spent their time discussing their next steps, without George.

On Friday January 17, he gathered what he'd shot so far and met with Apple's legendary publicist, Derek Taylor, at their offices at 3 Saville Row, who then suggested they show them to another key Beatles player, Peter Brown, whose office was on the 1st floor. "I was projecting these slides on the wall, and then into the room walked John & Yoko, George, Paul and Linda," he remembers. "I never did see them all together in one room ever again, unless they were recording." But, as he's showing his photos, "somebody says, 'Let's do a book,'" and Russell was then invited to continue photographing their work for the rest of the project. (That book did indeed appear, as described later.)

Ethan's photos – along with those of Linda's, and the aforementioned frame grabs – appear in the glorious new book, The Beatles: Get Back, a companion to Peter Jackson's Disney+ series, published October 2021 by Callaway Arts. The text is accompanied by transcript selections for each day from Sutton's Nagra recordings.

- Log in or register to post comments

Hey, thanks so much! It was quite a lot of fun to research and learn about from these great folks. I'm glad you enjoyed it.

The Beatles' iconic album "Let It Be" and Peter Jackson's documentary "Get Back" offer a captivating journey into the band's creative process. Jackson's film provides an intimate look at the making of the album, revealing the camaraderie and challenges faced by the legendary group. It's a must-watch for any Beatles enthusiast.

https://theauthorconnect.com/how-to-write-a-childrens-book-tips-and-tric...

.....Just a quick correction to info mentioned in the article about a camera used to film the "documentary"....

The article states: "The (Arriflex 16BL) cameras had 400 ft. film magazines, which ran for 21 minutes."

Actually, 400 feet of 16mm only lasts for 11 minutes if shot at 24 frames per second.

(And the image of the camera manual above the cited sentence is owned/copyrighted by "ARRI AG" of Munich, Germany, not "Apple Films Limited".)

(I've worked with and researched Arriflex cameras from about 1987 to 2006 and own an Arriflex 16-M camera.)

Thank you!

You're probably right re the run time on the 400 ft magazines. That came from Les Parrot himself, who was the camera assistant and second camera operator on the film. He said they went through 80 reels of film, through the whole project.

And thanks for the I.D. of the ARRI camera image - that had also come to us from Les.