Elton John: Farewell Yellow Brick Road

How do you close a 50+ year career in America, one which has brought music and magic to millions of fans, to celebrate with them? Well, if you’re Elton John, by returning to the city where it started—Los Angeles—and to one of the locations which symbolizes his incredible success, Dodger Stadium, where he famously played in 1975.

Elton John performed on Sunday, November 20, 2022, the third of three nights at Dodger Stadium. That night, he culminated his performances with a stylistically-enhanced experience that included special guests. Elton John Live: Farewell From Dodger Stadium was live streamed on Disney+ with a live edit and audio mix, shot with 28 cameras. That edit was available until January 27, 2023, when a new edit, making use of footage shot all three nights, and a new mix, became permanently available on the streamer.

“I had a very big, bold vision for what I thought Elton’s fans would want in a farewell tour - which we decided to call ‘Farewell Yellow Brick Road,’” a reference to his massive hit 1973 album,Goodbye Yellow Brick Road, says David Furnish, Elton’s husband and the tour’s Creative Director. “What would be the best way to celebrate him? “To take people on a journey of what he has represented as an artist and what he’s passionate about in his life. And what those songs mean to people. From his first appearance at the Troubadour in L.A., all those years ago, and what that meant for Elton, the opportunities it created. No one could have predicted it would become the path that it did. So this was a real opportunity.”

To help plan the lengthy tour, which began in 2018, Furnish brought in legendary Lighting Director and Show Director Patrick Woodroffe, whose work has not only included tours with Elton, but decades with The Rolling Stones, Dylan and others. “Beyond the all-important sound, rock shows have a lot of visual elements, as well as sound,” the designer states. “It is the stitching together of all of those elements is really key, and the successful show is the one where you cannot see the joins.”

Besides Furnish and Woodroffe, the creative team also included video content producer Sam Pattinson of Treatment Studio, and legendary creative director Tony King, who had worked with Woodroffe and Pattinson for many years with The Stones and others, and who put together Elton’s Las Vegas residency, “The Million Dollar Piano.”

The first step in developing a tour is deciding on the set list—no small task for a performer with a lengthy list of decades of hits. “There’s nothing Elton loves doing more than making lists!” laughs Furnish. “The show had to represent not only what the fans expected to hear, but also songs the band really enjoys playing.” The tour’s set list had 25 songs, with several added at Dodger Stadium to include duets with special guests.

The pace of such a show is terribly important, given its length. “Elton does a very long show—nearly 2 ½ hours,” notes Woodroffe. “And as much as anything is it a journey. One where he slowly reveals himself to us through the songs and through the things he says to us between numbers. By the time the house lights come up, you want to feel he is your best friend.”

Once the set list is in place, the next step is to begin developing, deciding what the appropriate visual accompaniment for each will be—“To give every one of those songs a completely unique identity,” says Woodroffe. “His songs are all different. They have different tempos, different sounds and different sensibilities—and different narratives. And our job”—the collective team mentioned above—“is to interpret that. How to light it, when you make a big resolution, when to use video content.” Things such as when to bring video content in—“Do you bring it in at the beginning, or wait until after the first verse, and then dissolve to a nice IMAG image (“Image magnification”—the live video images projected on screens from cameras at the venue)? And do you follow the color of the video on screen, and have an opposing color for it in light? It’s really like making a tapestry.”

The Stage

A major part of the presentation for a concert is the stage itself. This one—like many that have preceded it for decades—was designed by British entertainment architects Stufish. The company was founded by Mark Fisher, who worked with Elton’s team until his passing in 2013. His original former assistant, Ray Winkler, is now the company’s CEO and Design Director.

Winkler first met with Tony King and tour director Keith Bradley in 2015, at Stufish’s London office, to discuss a possible farewell tour design—how to make it special, for Elton’s final farewell. “The relationship between lights, sound, set and content is very, very tight,” Winkler explains. “And thankfully, I’ve known Patrick and Sam Pattinson for many years, so we’ve developed a shorthand, in which we understand one another’s requirements. And David was always very active and generous with important suggestions and direction.”

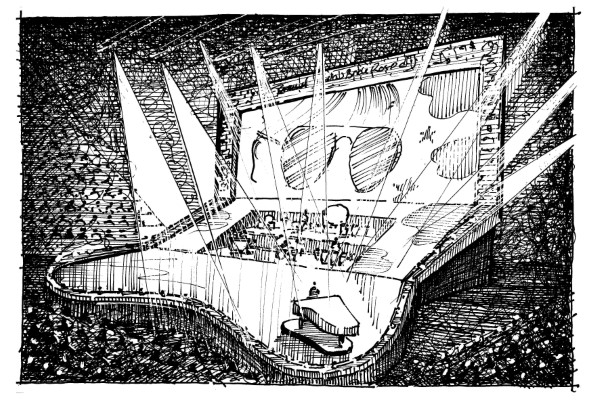

Laying out the initial stage design with some biscuits and fruit—“not even sketches,” he says—at that initial meeting, the three discussed things such as where the stage sits within an arena floor, whether it has “B” or satellite stage, connected with catwalks (it did not). “And how does one get Elton to come closer to his audience? Is he always stationed on Stage Right” per the established musician positions on stage? The design discussions continued over a period of 15 months, with Stufish presenting Elton & Furnish images, starting with hand sketches, to 3D computer models, allowing the two to see the designs using VR headsets, “So they could see what was happening. It was good fun.”

At its core, the design needed to reflect the way we all know Elton, Winkler informs. “Elton is about richness and opulence and texture and color,” so anything like a simple stage certainly wouldn’t do. The word “Gesamtkunstwerk” comes to mind. “That’s something Elton has always been very interested in giving the audience. It’s where all of the elements come together—set, lights, sound, scenery, special effects, video. That’s real quality,” compared to what he often sees in rock and roll stage design, “a mixture of eye candy and the profane.”

The stage features an undulating curved front, something which came out of those early conversations. “The idea is that it’s an embracing gesture, that the audience was embraced by the stage that was wrapping around them.” A mezzanine, above all of the other players, was provided for legendary percussionist Ray Cooper, because, simply, “He has so much gear”—countless percussion instruments played throughout the 2 ½ hours by the 75-year-old.

The centerpiece of the stage is a “Portal”—a large frame, hand-sculpted by artist Jackie Pyle and cast in fiberglass bas-relief and built by stage constructors Tait Technologies. The Portal is seen surrounding/above the band, and features items from Elton’s long career, in a gold frame, made out of yellow bricks (again, reflecting the Yellow Brick Road theme). “The whole idea of it is it’s a porthole into the entire scope and scale of his life,” Furnish explains. “Because Elton has been more than just a musician—he’s been a cultural avatar.” He and Elton sat down and listed as many iconic things from his life as they could, referencing everything from music, platform shoes, people he’s known (such as John Lennon, Leon Russell and his lyricist Bernie Taupin), The Lion King and much more. “We wanted to make sure everybody had a touch point to Elton.”

The detail may only be seen by audience members in glimpses on IMAG (though more clear to television audiences), but that wasn’t the point. “What I wanted was for it to be almost like a cradle that nestles him. And, for his fans, a throne he can sit on, that magisterially celebrates him.” Adds Winkler, “The point was that HE recognized his environment as being within it. It’s like a scrapbook David and Elton picked of their 20 favorite Elton moments. It became like this magic circle—it defined the territory in which Elton was performing.”

The portal wraps around the main screen, as well as two sloping screens on either side of the band, which extend the imagery down from the main screen. “The screen envelops the band, and transitions into a big vertical screen,” Winkler informs.

While the tour started out with that design, by the time it made its way to Dodger Stadium, Elton had, with rare exception, finished playing in arenas and was now in stadiums, requiring an adjustment to the design. “When we took the show into stadiums, you’re suddenly playing to four or five times more people,” explains Woodroffe. “So you have to make the show feel bigger, and you have to put some rain protection over the stage.” So Stufish built a large 50 ft. cantilevered, clear canopy—a pretty hefty structure—to cover the band area, in case of a storm. Doing so, however, separated the main screen from the sloping screens on either side of the band, so Treatment Studio created a digital frame of gold and other cool content, since the two screen surfaces were now separated from one another.

One thing about being the piano player in a 2 ½ hour show—you have to sit at the piano the whole time, something which Elton found somewhat frustrating. His Yamaha grand was placed near Stage Right, and, as Winkler notes, “He wanted to be able to address both sides of the audience, and not be biased to just one side.” So while brainstorming the tour design, the team came up with the idea of placing the piano on a large platform which could move across the stage at appropriate times. “Elton could sit at his piano and play, and, without missing a beat, it would slowly track from Stage Right to Stage Left, and then back again—and revolve.”

The platform—named the “Mobilator”—moved on a set of wheels, guided by a blade—like an inverted shark fin—which runs through a narrow 1/4” channel in the stage floor, on a gentle arc, and is operated by remote control. In addition, it sits atop a turntable, allowing it to be rotated when reaching the other end of its path, so that, instead of facing outward Stage Left, he faces Stage Right, and can see the band.

Besides the piano, the Mobilator also has traditional stage wedge monitor speakers. “Elton doesn’t use in-ear monitors,” says Furnish. “He likes to hear the fans—that’s what’s important to him. He needs to immerse himself in the atmosphere, to feel the whole environment he’s playing in, as well as hear himself. He has to have that connection.”

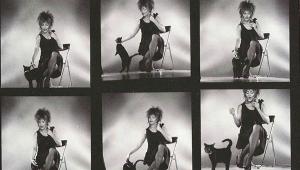

The Mobilator was used sparingly—on just two songs, most notably on the emotional “Candle in the Wind,” with Elton playing solo on the piano, as it tracks across the stage. “The story unfolds onscreen, recreating Marilyn Monroe’s last photo session with Bert Stern—images that Elton has in his own photo collection,” Furnish notes. “It’s really a beautiful, moving moment.”

The other important piece of movement for the artist addressed was, how does he make an exit at the end of the show? Since the theme of the tour was “Farewell Yellow Brick Road,” it was decided that upon finishing the last song—“Goodbye Yellow Brick Road”—that he would rise from his piano, remove his Dodgers smoking jacket, to reveal the shiny “ELTON” tour jacket—the same one seen in the original Ian Webb sleeve painting on the cover of the album. Elton moves onto a small, sloped moving platform—dubbed the “Travelator,” also built by Tait—rises up to the top of the stage and disappears—reappearing, via video content, inside the sleeve image seen on the large center screen, and walks off, down the Yellow Brick Road.

“We had to get him from the physical stage, somewhere close to the big screen, so that he can transition into the video, and then disappear, as a digital image,” Winkler explains. “Elton loved the idea of traveling up the slope, then the screen opens, he steps through it, and then appears as a larger than life Elton on screen, and walks up the Yellow Brick Road.” Adds Furnish, “He needed to step into the porthole, where we had a new revisionist take on the Ian Webb illustration, done by photographer David LaChappelle, which holds on the screen. And then Elton is going off to his new paradise. That’s the Yellow Brick Road for him now, with his family”—who made an extremely rare appearance with him onstage, including Furnish and their two sons, just before the end of the show. “He felt it was important that people, visually, could see, ‘This is what makes me so happy. Don’t worry—I know this is my last tour, but I’m gonna be fine. This is my family. This is the next chapter for me.”

The footage of Elton was shot by cinematographer Matt North and directed by Sam Pattinson. “Initially, he was going to do a bow,” says Pattinson. “And I suggested we could start on the ‘ELTON’ logo, as a graphic, and then we realize it’s on his back, as he walks away. And as he walks clear of the camera, we see that he’s in the Yellow Brick Road, wearing the same jacket we’ve just seen him wearing onstage.”

The moment was never something lost on Woodroffe, throughout the tour. “I’ve shed a tear many times at that,” he notes. “It’s really him saying goodbye to us.”

Video Content

As mentioned, the live video images of the band are referred to as “IMAG,” shot by a team of five camera operators, under the direction of the tour’s respected video director, John Steer. Unlike photography for television, which needs to present wide shots, as well as closeups, IMAG is essentially all closeups, just for audience members to be able to see the musicians’ faces and performances they can’t see from their seats.

Interestingly, even IMAG is used carefully and artfully on the tour. For instance, on “Philadelphia Freedom,” which features a particularly colorful and vibrant video, Woodroffe notes, “Even though it was only the second number, we decided to show only the film content and not put Elton on the screen at all. It felt right to focus on this hugely celebratory, amazing piece of film and save Elton for the next number.”

And coverage of the artist is generally fairly limited, he adds. “Because Elton performs pretty much the whole show sitting at the piano, we can only really shoot him from two or three angles. The shots are generally static, so if we stuck just with this on the main screen, it would eventually get boring for the audience. Switching to the side screens and using the alternative of the film content, is a way to balance the visual choices. Elton is very modest about himself on the screen. He often tells us, ‘They don’t have to look at me all the time!’”

The pace of cutting—switching from camera to camera—also varies through the show. “How fast a song is cut is also a way to give that particular number its own feel. Our live video director, John Steer, is very sensitive to this and will sometimes make a deliberately fast and frenetic cut for some songs while for others he will simply hold a single shot.”

The main video content, outside of IMAG, was prepared by Treatment Studio in London, recommended to Furnish by Tony King, who had worked with them on the Stones’ “40 Licks” tour and other projects—and did the video content for Elton’s “Million Dollar Piano” show Vegas in 2012.

The first step, once the set list had been decided, was for Elton and Furnish to sit down and come up with briefs on what they would like to see in the video work, though it was Furnish who did most of the conjuring. “Cause I’m the filmmaker in the family,” he chuckles. “Elton said, ‘You know me better than anybody, and know my visual history better than anybody. Go away, and tell me what you think we should be doing. And we’ll bounce ideas off each other.’ So I did, and then we sat down and fine tuned what we wanted to achieve.” He then brought those briefs to Sam Pattinson at Treatment and to Tony King, “And then they would go away and bring what we wanted to life.” Adds Pattinson, “And then, we were able to suggest ideas and aesthetics, working with and around David’s initial briefs.”

All 25 songs in the set received video treatment, Woodroffe notes. “If we stuck a different video up on that big screen every time, it would be like going to the movies. We don’t want that.” When to bring the video content into the song is also critical. “We would ask, ‘Do we bring the content in right at the beginning, and then, in the middle, dissolve to a nice piece of IMAG?’”

Indeed, Pattinson would coordinate heavily with Steer, to make good use of both Treatments content and IMAG. “The tendency is to want to just have the video content the whole time,” he says. “And we’ve come to realize, you have to turn it on and off, and not overwhelm or dilute it by having it on the whole time. John Steer is very generous and ego-free. We might start with a piece which is very video heavy, and then look to balance it with IMAG. And John’s very good at that. He looks for the right spots to do it. And he knows Elton so well, because he’s shot him for so long. He knows exactly when he needs a shot there. We would send boards to him, let him know what we were up to, and it got him thinking.”

Treatment would also look at shows Steer had shot before, which had less video content. “We’d look at the way John had shot those shows, and we’d follow that. For example, ‘Saturday Night’s All Right For Fighting,’ there’s not much video in there. It’s this fight scene that’s a minute long, on the center screen. And the rest of it belongs to the IMAG. Which is absolutely right.”

When the stage was being designed, says Woodroffe, it was decided to augment the main screen above the stage, oriented in a “landscape” position, with a pair of “portrait” screens to the left and right of the stage. “You can put a guitarist in there, you can have Elton on it. It gave us a way to focus on one person at a time.”