Elton John: Farewell Yellow Brick Road Page 6

As one can imagine, managing 28 cameras and turning them into a live streamed television broadcast is no small undertaking. But Paul Dugdale did just that, with the help of an experienced, fast-thinking team.

Brett Turnbull, of course, wasn’t present, leaving DP duties to a combination of James Rhodes and Noah Mitz. His own usual manner of doing things places him not in the production truck, but elsewhere. “Myself, I prefer to sit out at the lighting desk. I don’t like sitting in trucks. I prefer to be out at FOH, in the middle of the crowd, with my eyes on the show, and also the crew running it.”

His goal there is to keep an eye on both cameras and lighting. Most importantly, by viewing a set of camera monitors (which he can control with his own switcher). “I’ll call out if somebody’s out of focus, or if I feel somebody’s framing isn’t right, directly to them, via the comm system. But a lot of the time, I’m mainly cutting around pictures that are useful for lighting.” Because he’s seated amongst the three or four different lighting desks, he can pick a good time to communicate with the lighting operators. “If somebody is busy trying to call 20 follow spots, and I start trying to talk to them about something affecting camera shots, I’m probably going to annoy them.. or even worse, make them screw up the actual show! I prefer to be physically close by, so I can find a good moment to say, ‘This is too bright’ or ‘Can we have more of this?’ If I’m in the truck, I’m probably going to try and talk at the wrong time.”

On broadcast night, Rhodes and Mitz sat in the back of the “gallery” in the truck—the display of all 28 cameras’ images—directly behind Dugdale. “They would be watching the shots, and just be looking for any space for improvement,” says Paul Dugdale. “I was to James’s right,” Mitz explains. “My job, with James there, was to match the cameras. ‘Oh, look at Camera 15—does that look a little green?’ or ‘What’s happening on the follow spot on Camera 6?’” or noticing a little bit of shadow on one side of Elton’s face, or “Not enough light on the drummer,” and Woodroffe’s team of lighting directors would make the needed adjustments. “It’s constant, throughout the broadcast.”

Regarding cameras, in his prep for the show, Rhodes had thoroughly studied Dugdale’s camera book, getting a firm understanding of what the director was aiming for with each song and specific cameras. “Paul is so well-rounded, creatively and technically,” he states. “All of the groundwork had already been done.” His job, then, was to keep an eye out for places where improvements could be made, or suggest cool additions. “I look for opportunities to make things better, or to adjust things, to make Paul’s edit work better. I might say, ‘I know you’re thinking this, but what about that? That would be really fun for this moment.’ He might say, ‘No, don’t do that, do this’ or ‘Yeah, cool, let’s do that.’ It’s a matter of trying to just add value to what Paul has already prepared. He’s already thought about it all 1000 times, and knows every single thing about the show. So I’m just there to offer an additional perspective, if I spot something to offer him.” And, like Turnbull would do with the lighting directors, “Because Noah and I are right behind him, I can see how much he’s dealing with. And if he gets a quiet moment, and I’ve seen something, I can speak to him on the comm and say, ‘Hey, Paul—check that out.’”

Directing the 28 operators starts with having the right people behind each of those cameras, Turnbull states. “You need to work with people who love music, and who understand it. These guys are very experienced at filming live concerts, and they’re sensitive to what’s happening on the stage.” It’s much like shooting a documentary, he notes. “If you’re watching a situation unfold, watching a conversation between people—when you’re watching musicians, there’s a dialogue going on between them. If you can sense what’s happening, you instinctively know to go to that guy.” Says Dugdale, “We’re always driven by the music.”

As for direction directly from Dugdale, Turnbull says, “Paul is much like a conductor with an orchestra. You just need a few signals, here and there, to get them to gel. He’s often just nudging people. If somebody’s straying, he’s just bringing them back in. He’s normally guiding the operators, getting them back on track. Making sure that, stylistically, they’re operating the right way, that the pacing is good. If he doesn’t like their framing, he can get them to adjust. And if a guitar solo starts, before you know it, you have 20 operators on the guitar player. At that point, you need to pull some people off again—‘Shoot the bass!!’” he laughs.

Dugdale does not give shot by shot direction to the operators himself—he just can’t, with so much going on. For that level of communication, he relies on his Associate Director, Robin Mishkin Abrams. “Whatever notes Dugdale has given to the operators, she’s got a copy,” Turnbull explains. “And there might be notes that he’s given to her, as reminders to him, like, ‘Make sure and warn me when such-and-such is going to happen.’ She has all of the basic notes, breaking down all the music for the operators, in real time, ‘There’s a drum solo here. There's a guitar solo here. This is when the new guest enters, coming in from Stage Left.’ So she’s constantly speaking, and all the operators hear her voice, all the time. And that’s very useful. There’s no time for a director to remember to tell every operator what to do.”

Doing the actual button pushing, switching between cameras, is the Technical Director (“TD”), or, as they are called in England, Vision Mixer—Emmett Loughran. Not being a TD that Dugdale works with regularly, Loughran was present on Nights 1 and 2, to get a sense of the rhythm and flow of the show, the team using the second night as a dress rehearsal.

“There’s different ways of working,” Turnbull explains, “Sometimes directors like to call out every shot, and every cut. Other times the director prefers to let the TD find their own rhythm, and only call out specific shots now and then. More like playing jazz.” Rhodes agrees. “Emmett is a musician. He’s got his hands on the keyboard, and he’s just riffing with what’s happening on the show.” And, in those moments, the team comes together, Turnbull adds. “On our headsets, there’s a non-stop barrage of different voices talking at once. You’ve got the Associate Director counting the bars and describing the action on stage, the Vision Mixer cueing up shots, with the Director constantly making sure that every camera’s doing what they’re meant to be doing, steering the whole thing along. Plus the music underneath. It’s a horrible racket for those couple of hours! But also a joy, to see everything falling into the right place.

Dugdale’s cutting pace is measured. “The show doesn’t need to be choppy,” he says. “We don’t have to get all 28 cameras in every song. For ones where Elton and the band really up, and they’re jamming and really let loose, we certainly push the edit—knowing that a slower song is coming next. We’re just led by the music. And when you just want to watch Elton’s face, and get every ounce of emotion, then we’ll do that, and stay on it, happily, for a whole verse. Whatever the music demands. And the more dynamic you can make the flow, across 2 ½ hours, the more it keeps you interested, following the music.”

Indeed, variety and pacing matter. “On a show like this, if you cut every song like a music video, people would just be punch drunk, in two songs,” Turnbull notes. “Choosing shots and pacing them is very important.” It’s almost important for it not to appear too perfectly crafted, says Woodroffe. “You want it to look beautiful, for there to be energy to it. But you want it to look real. You don’t want it to look too perfect. It’s a rock and roll show.” Dugdale agrees. “There is something to be said about it being live, and everything that comes with that, the spontaneity of it. It’s a little rough around the edges here and there, so it gives it this feeling that we’re really on a knife’s edge, and anything can happen, because it’s live. There’s a real excitement about that.” Dugdale is also skilled at marshaling the troops, so that cuts across several cameras, all of which are moving, are moving at the same speed. “That’s the important part of my job, kind of being the conductor,” he states. “Cause all of those guys, individually, are amazing camera operators. But we need to get everybody moving at the same speed, so that something doesn’t suddenly come as a jolt—‘Whoa—that guys’ going way too fast.’ I’m just the moderator, making sure everyone is singing from the same hymn sheet.”

Distinguished, Grammy® and Emmy® Award-winning sound Mix Engineer Eric Schilling crafted the live music mix heard during the livestream (which was then, like the video, heard in playback, until the post edit arrived in late January). He had recorded Adele: One Night Only the previous year for Dugdale. His previous—and award-winning—credits include countless Grammy Award shows and others.

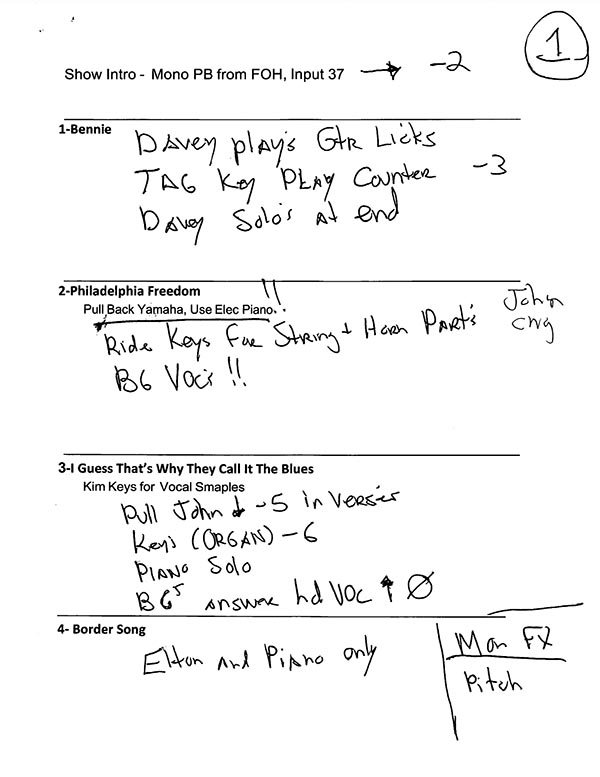

To help him prep, the broadcast’s lead production sound mixer—or “A-1,” as they are called—Mike Abbott, recorded Thursday’s show, with video, which Schilling then studied thoroughly the following day. “I’m a copious note taker, when I do live production,” he explains, “so that I’ll remember where cues are and important parts of each song. It’s essentially the set list, with piano solos, guitar solos, etc., notated.” For example, his notes for “Burn Down the House” indicate the keyboardist playing organ, Ray Cooper on congas and a note for “Push Elton” for Elton’s piano solo.

FOH mixer Matt Herr also popped in that day, and before Saturday’s show, to give him a bit of guidance, for things he might not be aware of. “On ‘Goodbye Yellow Brick Road,’” Herr says, “Elton, these days, sings the bottom part of that harmony. So, while for the rest of the song, he’s the loudest vocal onstage, you need to pull him back during the ‘Ahh’ harmonies. Things like that.”

Schilling spent Friday in the audio truck—separate from the production truck, but in the same compound—creating a mix, on his own, “Just to dial in sounds and get a mix going,” he says. The engineer works in a dedicated audio truck provided by Music Mix Mobile—or M3—the same facility he used for the Adele and Grammy broadcasts. Abbott, the A-1, meanwhile, responsible for the overall mix, sits in the production truck with Dugdale—Schilling’s responsible solely for mixing the music. Abbott will add other elements, such as audience mics, voice overs and other pieces outside of Schilling’s realm.

His feed of microphones comes from an audio splitter, located just behind the stage. The 80 mic inputs arrive, as analog signals, at the splitter rack, where they are then sent to three destinations: Herr’s FOH position, monitor mixer Alan Richardson’s desk, and to Schilling. In addition, Schilling gets Herr’s FOH mix sent to him, so he can hear Herr’s approach, as well as Herr’s effects returns, so that he can hear how those are used, as well. The A-1 will also send Schilling their final production mix and production elements, such as the applause mics, which will all get recorded onto one device—a Pro Tools file—to be used later for the remix done for the post edit. Schilling will also record his own mix, for reference by the post edit’s engineer.

As for the mix itself, though he could prepare audio “snapshots” of each song, to store on the mixing console’s software, like Herr, he does not. “I don’t have time to do that. So I rely more upon my notes. And I basically mix the entire show by hand—which I truly enjoy doing. You think in the moment, and you just go for it.”

His approach involved crafting a sound that replicated what audience members heard at the stadium. “If you’re watching a show that’s in a stadium, the sound needs to make you feel like you’re sitting in a stadium. So you don’t want it to be too washy, of course, where you can’t hear what’s going on. You want to find that fine blend between ‘I can hear the parts, and everything sounds fairly clear, but yet it’s got a room around it,’” to leave viewers feeling like they are at the show, with the people who are at the show.

Schilling did prepare a 5.1 Surround mix. “The rears tend to be more effects, not discrete music elements, because in a broadcast, when there’s stuff on screen, it can be distracting to people, to suddenly hear a guitar in the rear,” he explains. He also notes that he long ago learned to place the lead vocal not directly in the center channel. “There was a trend for a while, where people would take that vocal in the center channel and strip it out and play it by itself on YouTube. And if the vocal wasn’t spot-on perfect, the artists felt it made them not look so great. So acts started saying, ‘You cannot put my voice in the center channel.’”

With all of the important shows and artists Schilling has worked with, he notes, “I looked at this as a bit of a career highlight for me. Once I got there and got into it, I was, like, “Holy smoke—I can’t believe I’m getting to do this.”

The day after the Sunday concert, Dugdale and team were already receiving content and beginning to create their “post edit”—a new edit of the show, containing footage from all three nights of camera work. The job was done quickly, by editorial standards, Dugdale working with four different editors, delivering the finished cut on December 14. The show began running on Disney+ on January 27, replacing the original livestream edit and mix.

“The post edit is always good, because it allows us to be really precise,” Dugdale states. “We’re capturing things that we missed on the day, just because they’re happening in the moment. And it’s great to get all those things.” Dugdale describes himself as an “edit-driven director.” “I can be much more hands-on creative with the cut, and just help sculpt it into a more precise thing.”

He and his editors took Night 3 as the base, master show, with all of the audio coming from that show, as well. “Schedule meant we couldn’t stray too far from that show in the edit, using the other nights’ shots.” When he did, he did so with care. “Because the band plays live, and not to a click track, the timing of songs can drift slightly across the nights of the same song. The sync would drift, so you can’t just stay on one shot from another night, because you would begin to see the lip sync out.” And, thankfully, Elton and band wore the same clothes all three nights. “That was another awkward thing to ask of David [Furnish]—asking Elton if he would dress the same each night. But they were, like, ‘Oh, yeah, we were kind of assuming that would be the case. That’s no problem. Elton’s cool with that’—which was a relief.”

A new mix was created by legendary engineer and producer Chris Lord-Alge (Rush, Prince, Pat Benatar, Tina Turner).

“We had so much joy putting together the revised cut,” says Furnish. “We’ve been able to incorporate some additional camera work from the other nights, into something that I think is just visual and aural splendor.”

Says Dugdale, “You know, we can add some pizazz and glitter to that performance, from our camera movement and our cut. But, at the same time, we are documentarians. We’re capturing a moment, and it’s a really important one, in terms of Elton’s career, and music as a whole—and celebrating the influence he has had on modern popular music. It was a dream project to get to do, a total gift. An amazing artist in an incredible place. All we’re there to do is just serve the music and the artist, and hold on tight. And it’s a thrill, every time.”