LightRoom Is a pro-level editing app with free and premium features. you can download from here. LightRoom Premium apk

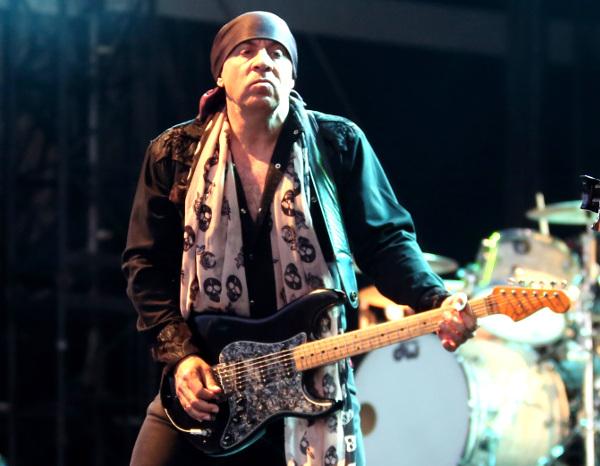

Little Steven Explores His Musical Roots in Soulfire

Indeed, the man also quite well known by his full name, Steven Van Zandt, really gets to spread his sonic wings on Soulfire, from the spot-on horns and of-era wah-wah that drive his cover of James Brown’s 1973 blaxploitation classic “Down and Out in New York City” to the gutbucket testifying of “Blues Is My Business” to the fervent reclamation of a song he wrote for Southside Johnny and The Asbury Jukes’ same-titled debut album back in 1976, “I Don’t Want to Go Home.”

I recently got on the horn with Little Steven, 66, to discuss when (and when not) to make political statements with your music, why radio is still an important listening avenue, and the ongoing importance of album sequencing in the modern world. Don’t be shy—the fat cats in the bad hats are gonna do you a big favor.

Mike Mettler: I was just talking with one of your Outlaw Country compatriots, Steve Earle, and we both agreed this might be the best time to have a straight-up rock record out there. Besides, we could just put on your 1984 release, Voice of America, and find a lot of its commentary still holds true today.

Little Steven: Yeah, that’s exactly right—and unfortunately true! (chuckles) It’s an interesting moment right now, because people have been going, “Oh, this is the perfect time for you to come out with a political record.” And I go, “No, I really don’t feel the need to do that anymore!” (chuckles again)

I felt like I had more freedom with this album, in a funny way. Even though all of my records have been very thematic, very conceptual, and very political, I just felt there was no need to be political here. Politics is always in the air now, and you can’t get away from it.

Mettler: How important do you feel radio is today? How vital is it to the current listening experience?

Little Steven: It doesn’t really change, but there is something really different about plugging in your phone and pulling up your playlists, or whatever it is these days to get to your own music when you’re in the car. Or, you can just listen to this voice coming out of the radio.

I think there’s something about human nature that enjoys that relationship, because it is a relationship. And the way I treat it on my channels is the way we did it growing up. We had a relationship with our DJs. We had a relationship with our radio stations. We trusted them, and we had a real energy and information exchange.

I also think there’s something nice about being surprised, you know? You don’t know what I’m going to say next, and you don’t know what I’m going to play next! (laughs)

Mettler: To me, that’s part of the discovery process. I like having somebody as the arbiter of taste. When I hear whatever the “Coolest Song in the World” is on the Underground Garage in any given week, I find it’s usually something I wind up buying, because sometimes I’m not all that familiar with the artist beforehand.

Little Steven: I love it! That’s what it’s all about, man; it really is. We do everything possible to encourage people to buy things. We know that’s an old-fashioned concept, but it’s how these guys live.

Mettler: It’s an exchange. You’ve gotta pay for your art.

Little Steven: That’s what I mean. And the more names people see in the credits, the more they’re going to realize, “Hey man, we need to support this in a real way.” And, by the way, that’s half of the reason the radio show was created. Yes, we are playing the best new bands, but we’re also playing the best music ever made, and this is the only place you’re going to hear it.

Mettler: I’m glad to see you did a double-album release for the vinyl version of Soulfire.

Mettler: I’m glad to see you did a double-album release for the vinyl version of Soulfire.

Little Steven: Yeah, yeah, that’s right. It’s three sides with music with an engraving on the fourth side, so it’s very cool.

Mettler: You didn’t want to contain this album to just one disc.

Little Steven: It would have actually been impossible. I mean, obviously, you’d have to take songs off, because it’s 57 minutes. You could squeeze maybe 40 minutes on a disc, but then you’d have to take songs off, and this thing fits like a glove the way it is right now, you know?

Mettler: It’s also perfectly sequenced as is. Isn’t that how you want people to listen to it, in the order you give it to us?

Little Steven: Well, yeah, we’re old school that way. I do realize kids don’t even know what the hell we’re talking about anymore (both laugh), but you hope people will listen to the whole thing as it is. People are going to have their favorite songs, but it does tell a story the way it’s sequenced. And it took me days to figure out the sequence, going back and forth on things. But it turned out really, really good, I think.

Mettler: Do you also think the younger generation is listening more closely now because they have to physically interact with the product, the album itself, instead of just punching a button?

Little Steven: Oh yeah. It’s a wonderful, wonderful trend, because not only do you actually get the pictures to see the band and see the artists, and realize it’s human beings making music—but you also get the credits. And don’t ask me why the credits were not a part of the normal download process from the beginning. I don’t know where the record companies and publishers were when these decisions were made, but it cost nobody nuthin, OK? It cost nobody nothing to download the credits automatically, but nobody did it! It was just so weird, you know?

Mettler: When I got records growing up, it was like reading the baseball box scores in the paper. You listened to the record, and you went through everything to figure out who was who and who played what, because there was nowhere else to look any of it up, really.

Little Steven: Exactly—and who wants to look it up anywhere else anyway? I don’t know why it wasn’t a standard thing from Day 1, you know what I mean? You just can’t believe these things happen—and they have consequences. You can’t overemphasize the value in the humanizing of music!

Mettler: That’s a good point, especially with a record like this where it’s very clear real people are playing the instruments. You’ve got the horns interacting with the guitar lines, and so many other musical elements coming together in each song.

Little Steven: Yeah, and it takes an army. You know the saying, “It takes a village…”? Well, it takes another village to make a record!

Mettler: It takes a rock & roll village, in your case.

Little Steven: (laughs heartily) That’s right!

Mettler: And you are the rock & roll village…

Little Steven: …Village Idiot!

Mettler: No no, we can’t say that! You’re not just “Down and Out in New York City”! (Little Steven laughs again) Speaking of that song, I think it may be my favorite track on Soulfire. Tell me about putting that one together, and why you pulled that James Brown track out of the hopper. [“Down and Out in New York City” originally appeared on James Brown’s soundtrack album for 1973’s Black Caesar.]

Little Steven: Well, blaxploitation is one of my favorite movie genres. I saw all of the old movies in the theaters around Asbury Park [New Jersey] when I lived there in the early ’70s. And from that blaxploitation movie genre came five or six fantastic theme songs, and this is one of them. It all started with “[Theme From] Shaft” [1971, Isaac Hayes] and then “Super Fly” [1972, Curtis Mayfield], “Across 110th Street” [1973, Bobby Womack], and “Trouble Man” [1972, Marvin Gaye].

Mettler: And you play all of these songs on the Underground Garage, too. You also have that special on every year on the day after Thanksgiving.

Little Steven: Yeah, we feature it every year on the day after Thanksgiving. People call it Black Friday, but we call it Blaxploitation Friday. We have fun putting it together, and it’s been one of my favorites for years.

And if it wasn’t for that blues festival that crazy promoter Leo Green asked me to play last year [London’s BluesFest 2016], I probably never would have thought to do that cover of James Brown’s “Down and Out in New York City.” It’s just not something you would normally do. But it opened up this whole other world to me now of covers in general. It’s a whole new sort of dimension I was never really able to explore before.

We all went through our different phases growing up where you take a little bit from here and a little bit from there, and blues was just a phase we went through. By the time we got the [Asbury] Jukes going and I was working with Southside Johnny [in the mid/late ’70s], I didn’t really have any desire to be my own performer or a frontman, so I was able to express my artistic creativity through him. He was vitally important. And he’s been out there all those years keeping my music alive, when I myself was not. He was extremely important in that sense. Just doing these songs again, from the other side of the microphone, made me appreciate him even more. These songs are not easy to do.

In the Jukes, we would throw a couple of blues things in there like “Little by Little” by Junior Wells, which I think was on the first album. [Actually, “Little by Little” is not on the Jukes’ 1976 debut album Don’t Want to Go Home, but it did appear as the B-side to 1979’s “Havin’ a Party” single, and it has since shown up on a number of Jukes greatest hits collections.] We were more into the rock meets soul straight-ahead type of thing, and so it’s nice to now say, “Wow. Let’s do a blues song.”

Mettler: Imagine the way you guys started bands back in the day from the ground up. Would you even want to start a band in today’s marketplace?

Little Steven: I don’t know! It’s a real question, man. It’s a real question. I don’t know. (pauses) I don’t know.

For us, we didn’t have a whole lot of life choices like there is now. Those of us who were really the freaks, the misfits, and the outcasts—like I’ve said, when the smoke cleared back then, everybody had a band in New Jersey. Everybody took every single option that was offered to them. But for us, it was me and Bruce Springsteen left standing there, and then it was like, “OK, where did everybody go?” (laughs heartily) So really, what I’m saying is, we didn’t have anything else.

Mettler: To wrap things up, I really feel like Soulfire is a 57-minute box set of your life. You pretty much cover all of the genres you have a love for or haven’t explored before, but have always been in your DNA.

Little Steven: I think that’s true. It certainly was a wonderful, wonderful sampling of it. It’s not everything, but if you combine it with the three-record set of Lilyhammer [the soundtrack collection for the show Little Steven starred in and curated the music for during its three seasons on Netflix], you have a pretty complete picture there.

This record turned out to be a really wonderful reset, reintroduction, and rebirth of myself. By the time you get in the studio for your first studio album, you’ve already developed to a point where you’re kind of already doing your own thing, so it was a wonderful opportunity to start again.

When we came straight back home from that London blues festival, we just took that energy right into the studio, because it really felt like something interesting was going on there, you know? So here, on this album, I’m really able to show off more of my roots in a way I had never done before.

- Log in or register to post comments