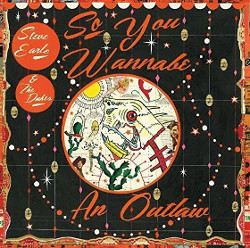

Steve Earle Embraces His Outlaw Country Roots on ‘Wannabe’

Earle embraces that concept of artistic freedom wholeheartedly within the 16 songs found on the deluxe version of So You Wannabe an Outlaw (Warner Bros.), which veers from the delicate touch of “Goodbye Michelangelo” to the heavier grit of “Fixin’ to Die.” No matter which facet of Earle’s strong personality is on display on Wannabe, he’ll be the first to tell you all of it was inspired by the original country outlaws themselves, Willie Nelson and Waylon Jennings. “I was listening to [Nelson’s] Shotgun Willie (1973) and Waylon’s Honky Tonk Heroes (1973),” Earle explains, “and I ended up on the back pickup of a Telecaster for two-thirds of the record.”

Earle, 62, and I got on the line to discuss how he approves final mixes in the modern recording era, the merits and pitfalls of digital vs. analog recording, the ongoing importance of vinyl, and whether radio play has ever had much impact on his long career.

Mike Mettler: You take great advantage of the stereo field on Wannabe. There are a number of subtle details way off in the corner in the right channel, for example, and we also get a good sense of the room you and your band recorded in together at Arlyn Studios in Austin.

Mike Mettler: You take great advantage of the stereo field on Wannabe. There are a number of subtle details way off in the corner in the right channel, for example, and we also get a good sense of the room you and your band recorded in together at Arlyn Studios in Austin.

Steve Earle: That’s all thanks to Ray Kennedy, who recorded it and mixed it, and Richard Bennett, who produced it. Sometimes we pushed it way further than we’re used to on this record, but I wanted it to sound pretty live.

I’m really less involved now than I used to be in the studio. I was always the guy who came in when we pushed the faders up and did the final mixes. But I’ve learned to trust Ray. I’ve worked with him for so long, so I don’t send around for mixes anymore. Now I’ve got a really good pair of headphones and a good set of converters, and they’ll send me fully modulated files. I listen at whatever the true resolution is, and hear the mixes that way.

But I will, in a pinch, approve stuff by MP3. I am interested in what the MP3 is going to sound like, because that’s how most people are going to consume it anyway.

Mettler: You’ve wrestled with the differences between digital and analog recording techniques over your career.

Earle: Right. I’ve now officially given up on tape myself, because it’s just not worth the expense and the trouble to me anymore. It’s about the songs more than anything else.

Guitar Town (1986), Exit 0 (1987), and Copperhead Road (1988) — those are all digital records. That’s all Mitsubishi digital multitracks to Mitsubishi 2-tracks to CDs. That was the rule. I didn’t have any choice, because [noted country record producer and longstanding MCA Records executive] Jimmy Bowen owned the machines, and you had to record on his machines if you recorded for MCA Nashville. So that’s why I recorded on them, period.

After I got out of jail [in the mid-’90s], I was a committed analog guy for a long time. It took a while for Pro Tools to catch up, and now, Pro Tools sounds really bleeping good. We still use a lot of old gear on the front end, though. We recorded this album in Austin on a true hybrid desk — a Neve console and an API console, married together. It’s perfect.

Washington Square Serenade (2007) was the first time I really did Pro Tools. And, of course, John King [a.k.a. King Gizmo, one-half of the production team known as the Dust Brothers], who I chose as producer on that album, would not work on tape at all. He just didn’t know anything about it, and didn’t want anything to do with it. He knew Pro Tools, and that’s what he wanted to do. So that’s what we did, and I think that record sounds great! And then Townes (2009) was made on my Pro Tools rig in my apartment in New York.

But when you’re recording bands live in the studio, you want the highest resolution available. It’ll sound pretty much like tape, and without the hiss. And I trust it now. I didn’t like the way it sounded for years — but now, I do.

Mettler: With a song like “You Broke My Heart,” where you’ve got the fiddle and the mandolin playing off of each other — if you didn’t capture that just right, you wouldn’t be happy with it.

Earle: No, And that mandolin is especially one of the best instruments I own, so it would break my heart if it didn’t sound the way it really sounds.

Mettler: And this is also the kind of record that you want to play on vinyl, which I’m glad to see has been rolled out as a four-sided record.

Earle: Yeah, we take a lot of care with our vinyl. We make sure it sounds really good. I own all of the Artemis titles like Transcendental Blues (2000) and The Revolution Starts Now (2004), and I’ve been manufacturing those myself for the last 2 or 3 years so we could sell ’em at shows and online, but not in record stores that much. But now that Warner has them, you may see them turn up more in stores.

Mettler: That’s nice to hear. Are you pleased with the vinyl versions of the other albums in your latter-day catalog?

Earle: I was a little underwhelmed by the Warner reissue of I Feel Alright (1996). I hated it because the vinyl artwork wasn’t that clear. Nobody consulted me, and I wasn’t crazy about it, so I’m going to try to fix that. And El Corazón (1997) still has not been reissued, so since I’m back on Warner now, we’re going to talk about it. It’s a really good record, and it’s a record people want.

Mettler: I’m one of those people myself. Why is vinyl still important to you, both as an artist and as a listener?

Earle: It just sounds good! Whatever we did, leaving that era — tape was a trade-down, even though you could play it in your car. CDs were a trade-down, even though we got to where eventually you could play ’em in your car. First, we were excited at how bright CD was — and I was excited by it at first too — but it took is a while to understand what we were missing.

And vinyl, of course, always took up a lot of space. But I’m in a good place right now. I just shipped a bunch of stuff to my house in Nashville because I now live in an apartment in New York. And I’m going to get a turntable in here again, so now I have to think about all the space it will take up.

I used to keep every record anybody ever gave me, and every record I ever bought. And now I’m much pickier about what I buy and the stuff I keep, because there’s not that much music worth owning, when it gets right down to it. (chuckles)

Mettler: It is a space issue, I agree. Are there certain records you still consider talismans, as in, “These are records I’ll continue to play for the rest of my life”?

Earle: Oh yeah, I think The Beatles in Mono on vinyl is a revelation, especially when you’ve forgotten it the way I did. I’ve got that Mono box back in Nashville. As soon as I get the new turntable setup here in New York, I’m going to order up another one just for here, because I could listen to that stuff every day.

Mettler: Just put the needle down on the mono version of “Taxman” [Song 1 on Side 1 of 1966’s Revolver], and there you go!

Earle: Oh yeah! And Sgt. Pepper (1967) — I think I always heard it in stereo because it was always available in stereo from jump. When [producer] T-Bone Burnett and I were making I’ll Never Get Out of This World Alive (2011), he was going through a major Sgt. Pepper-in-mono thing, because he had been the music director for a movie that had a lot of Beatles music in it [2007’s Across the Universe]. When I heard it in mono, it kind of just blew my mind, the way all that music sounded in mono.

Mettler: Coming back to the Outlaw record, I love that Richard Bennett is your producer, considering all the history you two have over the years. How did you guys get together for this one? Who chose who?

Earle: Well, he played guitar on the Colvin & Earle record (2016), and it was the first time we’d worked together in a while. Richard is essentially one of the producers on the Guitar Town and Exit 0 records. He’s the guitar player on both of them records, and we co-wrote a lot of that material together, like “Good Ol’ Boy (Gettin’ Tough)” and “Think It Over” [both on Guitar Town].

We always been friends. He’s always been one of my favorite guitar players, and he’s produced a lot of records I like. He also produced I Feel Alright. It was just time. Buddy Miller produced the Colvin & Earle record but Richard played guitar on the whole thing, and it was a blast to work together again.

Part of it is, I don’t have any original ideas about music. (chuckles) Transcendental Blues is based on [The Beatles’] Revolver and Rubber Soul, and Terraplane (2015) is largely based on Chess Records and mainly [Howlin’] Wolf, because that was my thing — I just love Howlin’ Wolf and all that stuff. And I saw Mance [a.k.a. blues maestro Maurice Lipscomb] and Lightnin’ Hopkins in the same room at the same time, so that stuff is also based on all that.

And, because of me and my age, it’s also based on Canned Heat and ZZ Top. Those are blues records and those are legitimate blues bands, so that’s where that came from. The Low Highway (2013) was [Neil Young’s] After the Gold Rush (1970) — that’s what we were aiming at; that kind of sound.

This new record is based on the [aforementioned] Waylon Jennings record called Honky Tonk Heroes, which was made in 1972 and came out in 1973, because it took RCA [Victor] forever to release it. Waylon was working with most of his own band for this record. It was all Billy Joe Shaver songs, and it was a really important record to me — and a really important record to the history of country music. Probably more than any other record, this one defines what people refer to as “outlaw music,” when it gets right down it. And I listened to it over and over and over again.

I wrote a couple of songs for the TV show Nashville, ironically, because T-Bone [Burnett] asked me to write one and then Buddy Miller asked me to write one, and then I had a couple of country songs. [Both Burnett and Miller have been executive music producers/composers on Nashville, a position Miller has retained since Season 2, following Burnett’s Season 1 stint.]

Meanwhile, while I’m finishing the songs for Colvin & Earle, I had a certain kind of pop and folkie song I had to add harmonies to. Then I thought, “Well, maybe my next solo record is a country record,” and I started writing in that direction.

Mettler: Did you guys cut all of Outlaw live in the room together? Was everybody pretty much looking at each other the whole time?

Earle: Yeah, we’re pretty much lookin’ at each other. Basically, Arlyn [Studios, in Austin] is good for that, which is where we recorded it. It’s drums, guitar, and bass, and when the electric Tele came out, the bassist, Kelley [Looney] was in the same room as the drummer, Brad [Pemberton]. And [guitarist] Chris Masterson was in the same room as the drummer; his amp was just in a different room.

Eleanor Whitmore was playing fiddle, so she was isolated in a booth. I was in a larger studio room at the front of the complex, and whenever Kelley had the upright bass, it was set-up on its own in my room and behind me when we started recording. We could go fluidly to whatever we wanted to do, and what we set it up in advance to do. We went from acoustic to electric pretty effortlessly.

[You can see all this physical positioning in action during some of the recording-session moments shown on the DVD that’s included in the Deluxe Version of Outlaw.]

Mettler: Since you have a regular show on the Outlaw Country channel on SiriusXM [Steve Earle: Hardcore Troubadour Radio], do you feel radio is still important to you in terms of exposure and getting your music out there?

Earle: It’s not. I only get played, for the most part, on non-comm[ercial] Americana or Triple A stations. There are a few commercial radio stations that play me, but it’s mostly public radio and [SiriusXM] satellite radio — and I probably wouldn’t get played there if I didn’t have my own show!

I’m not sure radio’s ever been important in my career. I had radio hits for about 30 seconds at the beginning of my country career, and after that, everything was done by touring and press.

Mettler: And then Copperhead Road (1988) crossed over a little bit, and got you into another universe.

Earle: It was just one of those deals where I figured out I wasn’t gonna be allowed to live strictly as a country artist. I had to find an audience that wasn’t dependent on country radio. I had been to country radio, and country radio banned me. It was a mutual decision to… (slight pause) break up.

Mettler: Little Steven plays “The Revolution Starts Now” on the Underground Garage on SiriusXM. How relevant is that song today? Is it the same as it was or more than it was when it was released 13 years ago, back in 2004?

Earle: Oh, I don’t know; I think it’s pretty f---ing relevant. But I can tell you this Outlaw record is probably the least political record I’ve made. And when I recorded it, I knew — I mean, the election hadn’t happened, and I had assumed Hillary Clinton was going to win, and we at least knew what that was, you know? It wasn’t what I wanted, but we knew what it was, because we’d had it before.

I thought about writing some more songs and doing something different, but I decided to release this record the way it is, and make it true to the musical vision I had originally. The next record is going to be just as country, but a lot more political.

Mettler: Can’t wait to hear that! Have you already written anything for it yet, or do you just have stuff in mind at this point?

Earle: I’m writing something for it right now. Stay tuned.